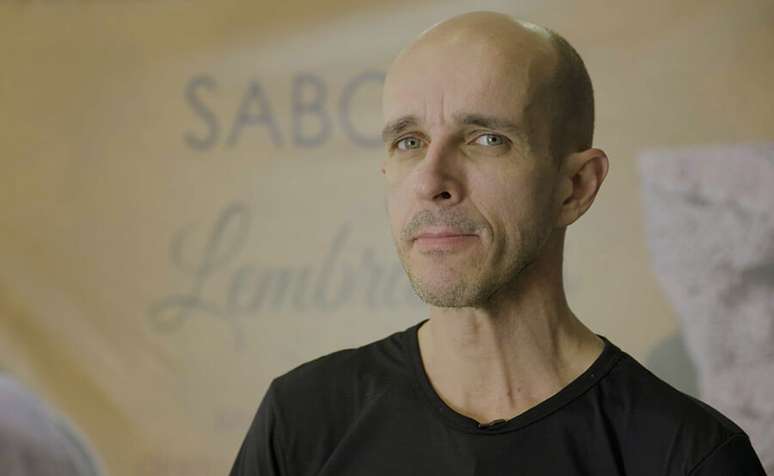

Moved by hope in its rawest form, Marcelo Haydu leads an organization that has already helped more than 10,000 people

html[data-range=”xlarge”] figure image img.img-ae7ad210b351cd7391451f102d7cc576vc5zulso { width: 774px; height: 476px; }HTML[data-range=”large”] figure image img.img-ae7ad210b351cd7391451f102d7cc576vc5zulso { width: 548px; height: 337px; }HTML[data-range=”small”] figure image img.img-ae7ad210b351cd7391451f102d7cc576vc5zulso, html[data-range=”medium”] figure image img.img-ae7ad210b351cd7391451f102d7cc576vc5zulso { width: 564px; height: 347px; }

There are so many and so significant incidents that have helped shape who Marcelo Haydu is today that it makes the task of selecting the best of them to begin his profile inglorious.

I could choose the story of his grandfather, who, hidden in the hold of a ship, fled completely alone from Hungary and the Second World War to an unknown Brazil. It wouldn’t hurt to say that, from his youth, Marcelo has been a volunteer helping the homeless, or that in a job he did during his undergraduate degree he had contact with refugees from African countries.

But there is also this personal journey, which culminated with the creation of Adus, an award-winning humanitarian institute for the inclusion of forced immigrants which already has a 13-year history: it took five years carrying the curricula of refugees under their arms, on their long walks looking for a job – a job that has come to many of those he has helped, but never to himself.

Perhaps what unites all these passages is the conjunction of two elements: indignation and hope. Indignation for human evils. Hope in its rawest form, without naive and childish flourishes about a better world. Hope as the raw material of creative rather than imaginative energy. Hope in humanity – in hers, in the other and in ours, collectively.

In a simplistic definition, refugees are immigrants forced by human rights violations, armed conflict or persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, sexual orientation, membership of a social group, etc. At the beginning of 2023, the refugee queue reached 134,000 people, the highest number since the National Committee for Refugees (Conare) was created in the mid-1990s. By comparison, in 2010 there were just over 600 requests pending. They are people of more than 70 nationalities, but 90% of them, according to Adus, come from four countries: Venezuela, Syria, Afghanistan and Congo.

“If purpose doesn’t come from the heart, it’s not something that’s ingrained, you can’t stand certain things that you go through. Purpose, for me, is the battery. It’s always on and that in times of adversity, of challenges, it plays, plays with it cheer up. Because we take a lot of falls,” Marcelo said, in an interview with the podcast Valley of Affliction. The episode has just aired, in the same month in which World Refugee Day is celebrated: 20/06.

In case you have any preconceived ideas about the downfalls of entrepreneurship, I ask you to drop it for a few minutes to absorb exactly what it relates to. Marcelo is an academic with a degree in International Relations, a Masters in Social Sciences and a PhD in Collective Health. The robust curriculum, then enhanced by specializations in the corporate field, will guarantee him great job opportunities, with substantial salaries both in the corporate market and in the public administration. This truth was repeated countless times even by his family, who did not understand how a man over 30 years old, with a wife and two small children, chose to help strangers without earning any compensation in return. There is no time to take care of your career.

From bridge to goal

The relationships Marcelo built with African refugees during his graduation didn’t end with the delivery of his academic work. Moved, he volunteered as a bridge to the job market. When, after five years, he couldn’t find a steady job, he decided to turn this support service into a formal job. Together with two friends, he founded Adus in 2010. “I believe there was a purpose behind me not getting a job. I couldn’t see any other reason to date.”

Three years later, Adus was already operating as a humanitarian organization, but it did not have a headquarters or pay salaries to Marcelo and his two partners. It had no partnerships and remained almost as dependent on the will of the people involved as before the foundation. According to the partners, it was time to shut down the business. Marcelo insisted on a deadline.

Knowing that it is better to apologize than ask permission, without notifying the partners, he contacted the language schools the following week, introducing the institution and saying that he needed support – which included teachers and teaching materials – to teach Portuguese to the refugees. An institute from Campinas returned offering help and asking how many professors the institute already had and where its headquarters were. “He went crazy at the time. I said that I had five people and that the headquarters was in the city center. She said that in 20 days she would come to São Paulo to visit the headquarters and start the partnership. We didn’t have any of that. The phone and I was like, ‘Oh my God, what have I done?'”

Marcelo had made Adus resist.

Today the humanitarian organization has about 30 formal collaborators and about as many volunteers. It receives donations from the private sector and from individuals. It has already integrated more than 10,000 people from various corners of the world. It has a professional administrative and financial structure, capable of promoting a career plan for the team. The challenges continue, as they will never cease to be. “Today I dedicate myself practically exclusively to Adus. It is a job that pleases me very much because it has to do with people. And although these people find themselves in very dramatic, sad situations, we somehow manage to give our contribution in order to have a more dignified life”.

Adriano Marchesini is a journalist specializing in IT, business and health with nearly 20 years of experience. After passing through the editorial offices of vehicles such as Estadão, Infomoney, ITWeb and CRN Brasil, he co-founded the agencies essense and Lightkeeper, which have already helped more than 80 companies in building multiplatform narrative content for businesses. She is co-founder of Unbox Project and co-host of the podcast Vale do Suplício. Created by journalists Adriele Marchesini andSilvia Noara Paladin

, the Vale do Suplício podcast was born as a counterculture to stage entrepreneurs – the typical MEI CEOs, LinkedIn text writers – to tell the story of entrepreneurs who say little, but do a lot. Listen on Spotify.

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.

![A Better Life Preview: What’s in store for Tuesday, October 21, 2025 Episode 446 [SPOILERS] A Better Life Preview: What’s in store for Tuesday, October 21, 2025 Episode 446 [SPOILERS]](https://fr.web.img6.acsta.net/img/fe/c7/fec79870332faf9ba9cf244248ec57c8.jpg)