The study analyzed the skeletons of 369 people who died in 1918 during the wave of cases of the disease.

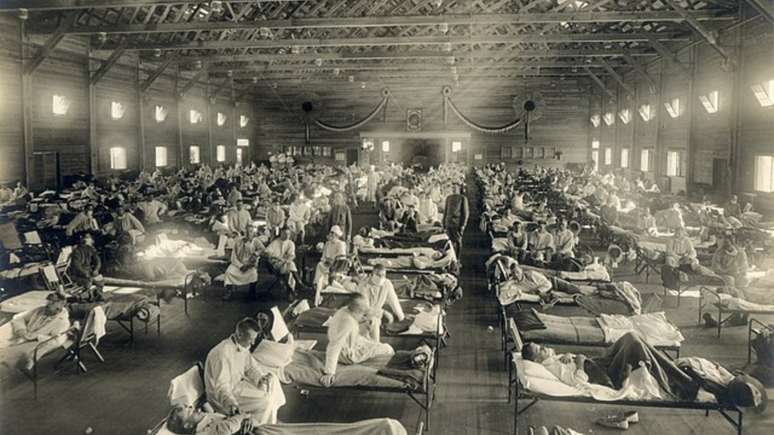

The Spanish flu pandemic that swept the world in 1918, killing an estimated 50 million people, has long been associated with the idea that it indiscriminately affected both the young and healthy and the most vulnerable. However, a new study, published in the journal PNAS on October 9, challenges this myth.

Researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder), in the United States, and McMaster University, in Canada, conducted a bioarchaeological analysis of age-at-death and skeletal injury data from 369 people who died before and during the influenza pandemic. 1918 in the United States.

The results were surprising, showing that, in fact, individuals who had already been exposed to environmental, social and nutritional stressors before the pandemic were more likely to succumb to the Spanish flu virus. This trend has also been repeated in subsequent health crises, including the Covid-19 pandemic.

Research co-author and professor of anthropology at CU Boulder, Sharon DeWitteunderlined, in a statement:

“The idea that the 1918 flu killed young, healthy people is not supported by our findings. Instead, we discovered that this pandemic, like many others throughout history, has disproportionately killed vulnerable people.”

Popular tale

DeWitte pointed out that the belief that the Spanish flu killed healthy people may have begun as folk wisdom and perpetuated in literature, turning into a false historical truth.

She argued that historical documents often privilege the perspective of the most privileged, neglecting the reality of women, children and the marginalized.

For the research, DeWitte and his colleague Amanda Wissler, assistant professor of anthropology at McMaster University, consulted the Hamann-Todd human osteological collection, which contains more than 3,000 centuries-old human skeletons and is located in the basement of the Museum of Natural History in Cleveland, United States.

The analysis carried out by Wissler, which involved observing porous lesions on individuals’ shins, indicating trauma, infection, stress or malnutrition, revealed that the most frail were 2.7 times more likely to die during the 1918 influenza epidemic.

Various factors

The researchers suggest that factors such as socioeconomic status, education level, access to healthcare, and institutional racism may have played an important role in the vulnerability of some groups during the Spanish flu pandemic, similar to what happened in pandemics subsequent events, including Covid-19. 19 pandemic.19.

However, they point out that more research is needed to investigate this issue. These findings have significant implications for modern pandemic preparedness, highlighting the importance of understanding the complexity of affected communities and highlighting the limitations of relying solely on written texts to understand history.

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.