On March 11, 2020, Tedros Adhanom, director general of the World Health Organization (WHO), declared the world in a state of pandemic due to contamination by the new coronavirus (Sars-Cov-2). In three years, the disease scourge caused the deaths of around 15 million people around the world, as revealed by the latest report drawn up by the agency, until the pandemic status passed after a massive immunization campaign .

Among all the negative aspects, the pandemic has also promoted advances in science and health, accelerated the adoption of flexible working hours and online education, increased awareness about public health and its importance, increased the digitalization of economy, introduced technological innovations and established new sanitation protocols.

Only those who haven’t changed everything. In 2020, a report published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) had linked attitudes that cause climate change to the propensity for the emergence of new viral diseases. An article published in the magazine Advanced Studies highlighted the need for profound changes in relation to sustainable global development and the way the planet manages its natural resources, since viruses are a component of biodiversity and proliferate more in countries where there are socioeconomic imbalances and environmental changes.

If countries adopt an appropriate stance in the face of global warming and the constant acceleration of the means of production, it is possible that new pandemics could be stopped in the context of the biodiversity crisis. After all, experts have already clarified this the next pandemic must occur in the agricultural sector.

Producing too much

Since the second half of the 20th century, when the most relevant epidemics of modern times occurred, it has become clear that we need to rethink our relationship with animals, the way epidemics are linked to their husbandry and the food industry. Between 1970 and then, around 500 new zoonotic diseases emerged, such as avian influenza, Ebola, Nipah virus, HIV, Zika and even Covid-19.

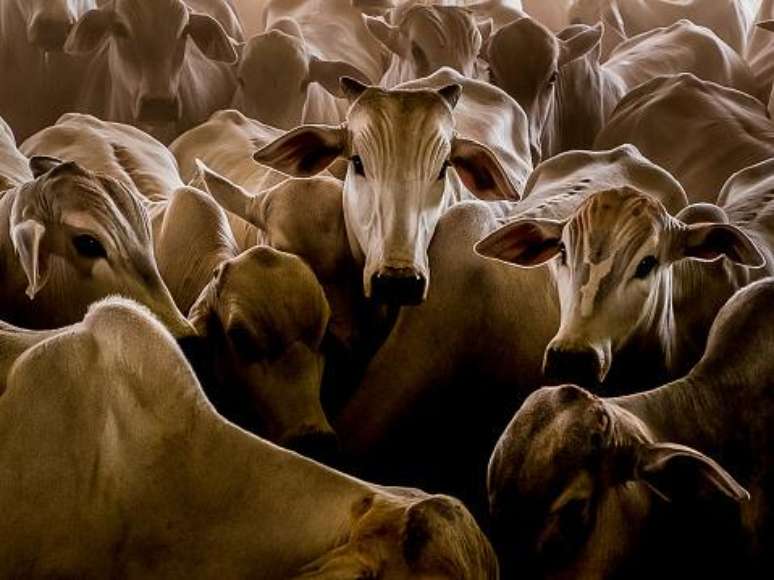

Humans have never been so close to pathogens from other species, and that’s because we’ve never bred so many animals so intensively. In 2018, research center Faunalytcs estimated that more than 70 billion land animals are slaughtered for the meat industry. The Global Agriculture organization points out that 60% of the world’s agricultural land is used for meat production, even though it represents less than 2% of the calories consumed globally.

To maintain production levels, the industry needs to confine thousands of animals, usually under adverse conditions, in overcrowded and completely unnatural locations. As a result, factory farms have become disease breeding factories, incubating and enhancing pathogens and allowing them to interbreed and proliferate in flocks, reaching humans in a hypervirulent state. This gives rise to outbreaks that evolve into epidemics and can reach pandemic status.

This behavior of the industry, which aims for high returns, is the same throughout the food production chain. The difference is that in the livestock sector we see the consequences in the form of disastrous consequences on a global scale, while agriculture has suffered a worrying decline since the last century.

The corn problem

A 2019 report, published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, states that 40% of the planet’s land is covered by farms. Currently, nearly 50% of systems consist of just four crops: wheat, corn, rice and soybeans. We’ve already seen that diseases are common, it’s no wonder that, globally, $30 billion of food is lost to pathogens every year.

Miguel Altieri, professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, answered the question THE ground that all the conditions are right for a pandemic to occur in agricultural systems, causing global hunger and catastrophic economic difficulties. And climate change increases this danger because it disrupts the distribution of pathogens and brings them into contact with new plant species, potentially worsening crop diseases.

This was the case in the summer of 1970 in the United States, when the mushroom Bipolaris maydis it caused a disease called southern corn leaf blight, which causes the stalks to wilt and die. The disease scourge has ravaged the southern United States into the Midwest, reducing the corn crop by about 15%, generating $1 billion in losses.

The episode caused the North American population to lose more calories in their diet than the Irish during the Great Famine of 1840, when potato fields were decimated by disease.

Unprecedented damage

But this fungus only affected corn crops in this way because the industrialization of the food system, which began in the early 20th century, led scientists in the 1930s to develop a variety of corn with altered genetic uniformity to generate yields higher. This specific variety, known as cms-T, forms the genetic basis of 90% of corn grown in the United States and has been shown to be highly susceptible to corn leaf blight. Therefore, when there was an exceptionally warm and humid spring that favored the fungus, it had an immense amount of product to burn.

“Never again should a large cultivated species be so uniformly patterned as to be so universally vulnerable to attack by a pathogen,” wrote plant pathologist Arnold John Ullstrup in an article on the subject published in 1972.

Despite the damage that this genetic uniformity can cause, it constitutes one of the main characteristics of most large-scale agricultural systems today. As the production machine speeds up, more changes are made and plants become more susceptible to epidemics.

As long as systems are based on monoculture, which only attracts losses, and biodiversity is not incorporated into large-scale agriculture, the crisis tends to become increasingly greater, because, as Altieri himself underlines: “we create amplification and not dilution “.

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.

![Tomorrow Belongs to Us: What’s in store for Monday 3 November 2025 Episode 2066 [SPOILERS] Tomorrow Belongs to Us: What’s in store for Monday 3 November 2025 Episode 2066 [SPOILERS]](https://fr.web.img3.acsta.net/img/90/4b/904bf0916a3afede10b3575c799a9882.jpg)