Memories are not the exact record of the past, as we would like to imagine. According to the researchers, scientific studies have confirmed, more than once, that the way we remember is inevitably flawed and usually has little relation to verifiable events.

Have you ever perfectly remembered leaving your keys in a certain place, so if they’re not there it’s because someone took them, only to discover they were always in your pocket?

Or have you ever heard a friend tell you about something that happened to you and their story was very different from what you remember?

These experiences leave us a little unsettled. But they occur frequently and sometimes we don’t even notice them.

“Everyone has false memories all the time, even those who think they have the best memory in the world,” says psychologist Julia Shaw, of University College London.

Shaw refers specifically to autobiographical memory, “the memories of our lives that are often accompanied by a note titled ‘multisensory components’: remembering how you felt, what you knew, how you saw yourself, how you dreamed… with strong emotions ” .

“These [lembranças] they are much more complex than [recordar] an event,” Shaw told the program Scientific lifefrom the BBC.

To remember an event – for example “on September 11, 2001 there was an attack on the Twin Towers in New York” – it is not necessary to access many places in the brain.

But, when we relive our experience, it is necessary to connect all the parts of the brain responsible for the different sensations, forming a vast and complicated network of neurons.

Shaw warns that memories are not the exact testimony of the past, as we would like to imagine. According to her, scientific studies have confirmed, more than once, that the way we remember is inevitably flawed and usually has little to do with verifiable events.

Identity crisis

“We are our memory, we are this immense museum of inconstant shapes, this mass of broken mirrors”, said the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986). He was able to understand very well that memories are dynamic, changing and imprecise realities.

But if “we are our memory” and it is so unreliable… are we lies?

In a certain way, yes. But the fact that we can never be sure that what we remember is correct shouldn’t worry us, according to the expert on false memories.

“I think it’s a really important insight into how our brains work,” explains Shaw. “And ultimately, our brains don’t simply exist to record the past perfectly and reliably. They’re there to navigate the present and think about the future.”

“These wonderful, creative things are great for solving problems, they allow us to be intelligent, they creatively recombine information gleaned from the past and put it together in ways we’ve never done before, to create a new story, a new solution or a new idea.”

“It is adapted for this, and therefore things like false memories are a byproduct of this incredible intelligence capacity,” says the psychologist.

Shaw describes memories as undried clay dolls. “Every time you take a piece again, you reshape it and potentially create another one that is very different from the last one.”

“You remove and add parts, because you forget some or borrow memories from other people or other sources,” he explains. “The interesting thing about memories is that we don’t have access to the original version, only the one we made last time.”

Intriguing or disturbing?

Perhaps both… and perhaps as much as the experiments developed by Shaw and other experts in this field.

Memory implant

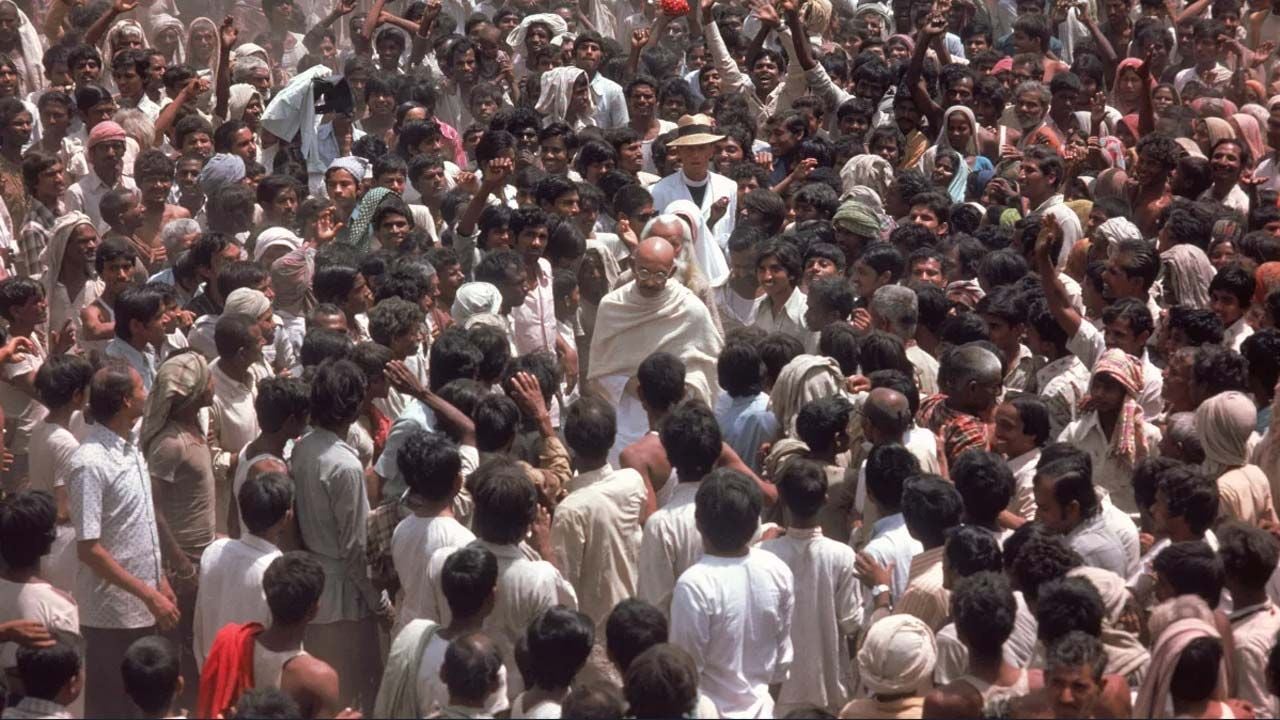

Shaw became famous for an experiment that was part of her doctorate. You demonstrated how a group of students create false memories.

We’re not talking about small details. The students ended up describing how, just a few years earlier, they had attacked people or been attacked by an animal, events that had not actually happened.

But they didn’t do it alone. Shaw got them thinking this way in just three sessions. He used information provided by the volunteers’ parents to implement the memories.

After gaining her trust, she will say, for example, that her parents told her that when they were 14 they attacked someone with a gun and called the police.

“Then he would introduce real-life details, like ‘your friend Alan was there,’ and say it happened where they lived at the time,” explains Shaw. “It’s enough to make someone think ‘maybe it happened’.”

Then he offered to help them remember what he knew couldn’t be remembered. And she led them in imaginative exercises.

“In the end, the amount of information they provided me far exceeded my expectations,” says the psychologist.

And that’s not all: “a staggering 70% of the participants in our study created false memories of illegal activities. From a purely scientific point of view, it’s exciting,” he emphasizes.

And from a human point of view?

After all, he led a group of volunteers through weeks of very unpleasant memories, only to later reveal that they had been deceived.

The psychologist points out that the study “received wide ethical approval, which was natural because it was a big manipulation.” And he guarantees that, after explaining to the participants what the study was about, “most felt relieved and none of them were outraged – or, at least, they didn’t tell me”.

From his perspective, “it was a great learning experience.”

“Our memories are influenced by people, usually unintentionally, all the time,” explains Shaw. “Therefore, I believe it is convenient to teach people to be aware of this and understand how this process works.”

Why was the study done?

“I wanted to study something called criminal thinking,” he explains. “I’ve always been interested in the ‘normal’ brain, not so much the pathologies, but how ordinary people can become criminals.”

That’s why Shaw wondered if he could get people to plead guilty to crimes they didn’t commit.

“Not only did they say they did it, they actually believed it,” he says. “The answer is: yes, it is possible.”

This is a manifestation of the fragility of the “curtain that separates our imagination from our memory,” as the most eminent psychologist in this field, Elizabeth F. Loftus, who conducted similar experiments, wrote.

In the dock

The North American Psychological Association considers Loftus one of the most important psychologists of the 20th century, who contributed to changing the dominant idea until a few decades ago, according to which our memories were literal representations of past events, preserved in a sort of library mental. .

Loftus has written dozens of books and argues the opposite, that “our representation of the past is a living and changing reality.”

“It’s not some place back there that keeps everything in stone, but a living thing that changes shape, expands, shrinks, and expands again — an amoeba-like creature,” he says.

Memories are not reproduced, but rather reconstructed.

In addition to offering fascinating insights into how the mind works, research on the science of memory has had implications for criminal justice, which relies heavily on statements from witnesses and suspects.

Few psychologists have been more influential than Loftus in revealing how standard procedures in this field can contaminate memory.

The language used to describe an event can change how it is remembered. Therefore, biased questions can distort suspects’ statements during police interrogations and even the reports of defense or prosecution witnesses.

This possibility means that experts like Loftus and Shaw are often called upon to examine evidence in court cases.

“We almost always get hired by defense, not because we want to, but because of the nature of our work,” Julia Shaw points out. “Because questioning someone’s memory has the ability to introduce reasonable doubt.”

In most justice systems, prosecutorial evidence must overcome a reasonable doubt to substantiate a criminal conviction.

If at any stage of the process, applying the science of false memories, we detect possible manipulations that could generate distorted, altered details or even completely implanted memories, “we raise the alarm signal,” according to Shaw.

He points out that understanding how fragile and misleading our memories are helps avoid miscarriages of justice.

It seems to be beneficial, but many people wonder if questioning someone’s memory in court could make it even more difficult for sex crime victims to testify.

Several trials of high-profile defendants have employed Loftus as a defense witness and appear to justify this concern, including the trials of Bill Cosby, the Duke lacrosse players in the US accused of rape in 2006, and Harvey Weinstein, among others.

It is clear that the presumption of innocence always prevails and that everyone deserves the right to defense.

But in cases of abuse, which often involve one person’s words against another, it is especially difficult to see how memory science can challenge the memories of victims forced to relive that moment.

“You have to be very careful and not consider that memories are not sufficient evidence. That’s not the case,” Shaw emphasizes.

“If we couldn’t rely on memories, our legal system would collapse and some types of crimes would never be convicted.” The key, for the specialist, is to “educate the public”.

“I always recommend that if it happens to you or if you witness something important, you record it outside of your brain,” Shaw says. “You need to understand how your memory can change so you can preserve it as much as possible.”

Listen to the episode of the BBC Radio 4 program “Scientific life” (in English), which gave rise to this report, on the website BBC Sounds.

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.