A recent survey found that 25% of people between the ages of 18 and 34 never answer their phone. Participants said they either ignored the ring, responded by text, or looked up the number online if it was unknown.

“Hi, this is a voicemail from Yasmin Rufo. Please do not leave a message because I will not hear from you or call you back.”

Unfortunately, that’s not the message on my answering machine. But I certainly wish it was, as would most Gen Zers (born 1995-2010) and Millennials (born 1981-1995).

A recent survey found that 25% of people between the ages of 18 and 34 never answer their phone. Participants said they either ignored the ring, responded by text, or looked up the number online if it was unknown.

The survey on the Uswitch website involved 2,000 people. It was also concluded that about 70% of people between the ages of 18 and 34 prefer SMS to phone calls.

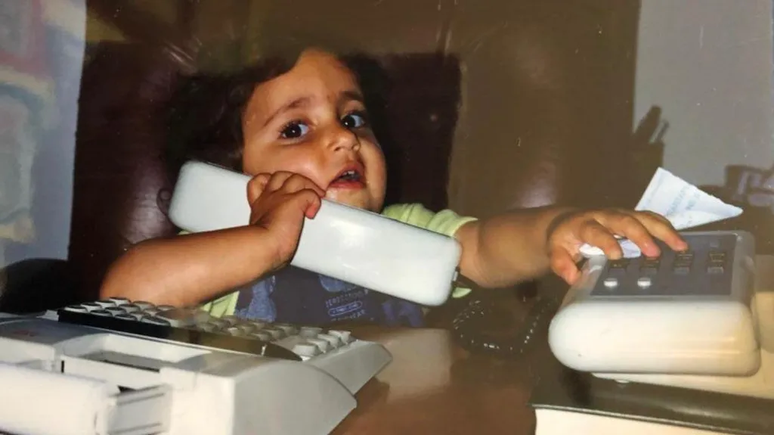

For the older generation, talking on the phone is normal. My parents spent their adolescence arguing with their siblings over the landline in the hallway, which only meant the whole family was listening in on their conversations.

My teenage years were spent texting. I’ve been obsessed with it ever since I got my pink Nokia as a birthday present when I was 13.

I spent every evening after school composing 160-character texts for my friends.

I removed all the unnecessary vowels and spaces until the message looked like a bunch of random consonants that even the secret services would have a hard time deciphering. After all, I would never pay extra to write 161 characters.

And in 2009, cell phone calls cost a fortune. “We didn’t give you this phone so you could gossip with your friends all night,” my parents reminded me every month when they got my phone bill.

Thus emerged a generation of people who communicate only through text. Cell phone calls were for emergencies and landlines were rarely used to talk to grandparents.

Psychologist Elena Touroni explains that, since young people are not yet used to talking on the phone, “now it seems strange to me, because it’s not normal.”

Young people can therefore expect the worst when their phone starts ringing or going silent, because no one under 35 has a ringtone set on their phone.

More than half of young people who responded to Uswitch’s survey admitted that they think an unexpected call means bad news.

Psychotherapist Eloise Skinner explains that anxiety around phone calls comes from “an association with something bad, a sense of fear or foreboding.”

“As our lives become busier and our work schedules more unpredictable, we have less time to just call a friend to check in,” she explains. “That’s why phone calls are reserved for the important news in our lives, which can often be difficult.”

For 26-year-old Jack Longley, “that’s exactly it.” He never answers calls from unknown numbers, because “it’s either a scam or marketing. It’s easier to ignore the calls than to try to find out which ones are real.”

But not talking on the phone doesn’t mean young people aren’t staying in touch with their friends. Our chat groups are busy all day, with a variety of common messages, memes, gossip, and more recently, voicemails.

Many of these conversations now happen on social media, especially Instagram and Snapchat, where it’s easier to send pictures and memes alongside texts. And despite the consensus that phone calls are unwanted, the use of voice messages is divisive among younger generations.

In the Uswitch survey, 37% of people between the ages of 18 and 34 said voicemail was their preferred form of communication. On the other hand, only 1% of participants between the ages of 35 and 54 preferred voicemail to phone calls.

“Voice messaging is like talking on the phone, only better,” says student Susie Jones, 19. “You have the benefit of hearing your friends’ voices, but without the pressure. So it’s a more polite way to communicate.”

But I have a hard time listening to five-minute voice messages from a friend telling me the latest news about her life. They fantasize, the messages are full of words like “like” and “uh” – and the whole story could be told in two text messages.

Text and voice messages allow young people to engage in conversations at their own pace. And they can respond more thoughtfully and thoughtfully.

Phone phobia at work

But how much does the phobia of phone calls in your personal life affect your professional side?

Attorney Henry Nelson-Case is 31 years old. He is also a content creator, and his video series about “devastated millennials” is incredibly relatable.

Scenes include the anguish of sending a company-wide email, the polite refusal to work overtime, and, of course, a video showing an employee going to great lengths to avoid a phone call.

He says that “the anxiety associated with real-time conversations, the potential awkwardness, not having the answers, and the pressure to respond immediately” make him hate talking on the phone.

“Phone calls expose us more and require a higher level of intimacy, while text messages are more distanced and allow us to connect without feeling vulnerable or exposed,” explains Elena Touroni.

Attorney Dunja Relic, 27, says she avoids calls at work because “they can take up a lot of time and delay work.” Eloise Skinner describes it as “it could have been an email.”

“There’s a growing sense of protection in our time,” she explains. “Calling someone requires the person receiving the call to take a break from their day and pay attention to the conversation, which is difficult for people who multitask.”

Businessman James Holton, 64, says his younger employees rarely answer his phone calls: “They either have a standard message saying they’re busy, or they forward my number, so the call never comes through.”

“They always have an excuse up their sleeve,” Holton says. “The most common one is ‘my phone is on silent, so I didn’t see the call and forgot to call back later.'”

He says he had to adapt after realizing there was “an obvious communication gap.” “If employees feel more comfortable with texting, it’s my responsibility to respect that decision.”

But does the preference for written communication and the tendency to work from home make us lose the ability to have informal, unplanned conversations?

For Skinner, if the current trend continues, “we may lose the feeling of closeness or connection.”

“When we communicate verbally, we feel more aligned, emotionally, professionally, or personally,” she explains. “This connection can create a greater sense of accomplishment, especially in the workplace.”

But supermarket manager Ciara Brodie, 25, bucks the trend. She says she “loves it and recognises it when my bosses at work call me.”

“It’s more thoughtful than texting because it requires a certain level of engagement that really lets you know that your manager values your information,” she explains.

She especially enjoys chatting on the phone with colleagues on days when she works from home. “It can be lonely, so it’s nice to stay in touch.”

Some might say that this new communication trend is further proof that we are the “snowflake generation”. But in reality, we are very far from this.

It’s more about adaptation. Of course, 25 years ago people were reluctant to switch from fax to email, but the change has made our communication much more efficient.

Maybe it’s time to recognize the power of text, and just as we retired the fax machine in the 1990s, we can leave the dreaded phone call behind in 2024.

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.