Discreetly released in Spain on platforms, ‘Magic Mike’s Last Dance’ delves into the postulates of the saga and its poetics of bodies

It has been of little use cult status than the previous two installments of ‘Magic Mike’, of 2012 and 2015, have acquired over the years: the final link in the trilogy, ‘Magic Mike’s Last Dance, It has not gone through Spanish cinemas. Available from Friday March 24 on Movistar Plus+, it is true that the film was originally conceived as an exclusive release on streaming, until the new management of Warner made the decision to take it to American theaters in February. Although far from the figures of its predecessors, which worldwide crossed the 100 million dollar collection despite your budget indie, the film has saved the furniture commercially despite a low profile promotional campaign and limited distribution, proof of the unconditionality of the fans and, above all, female fans that the saga has been generating in its ten years of life.

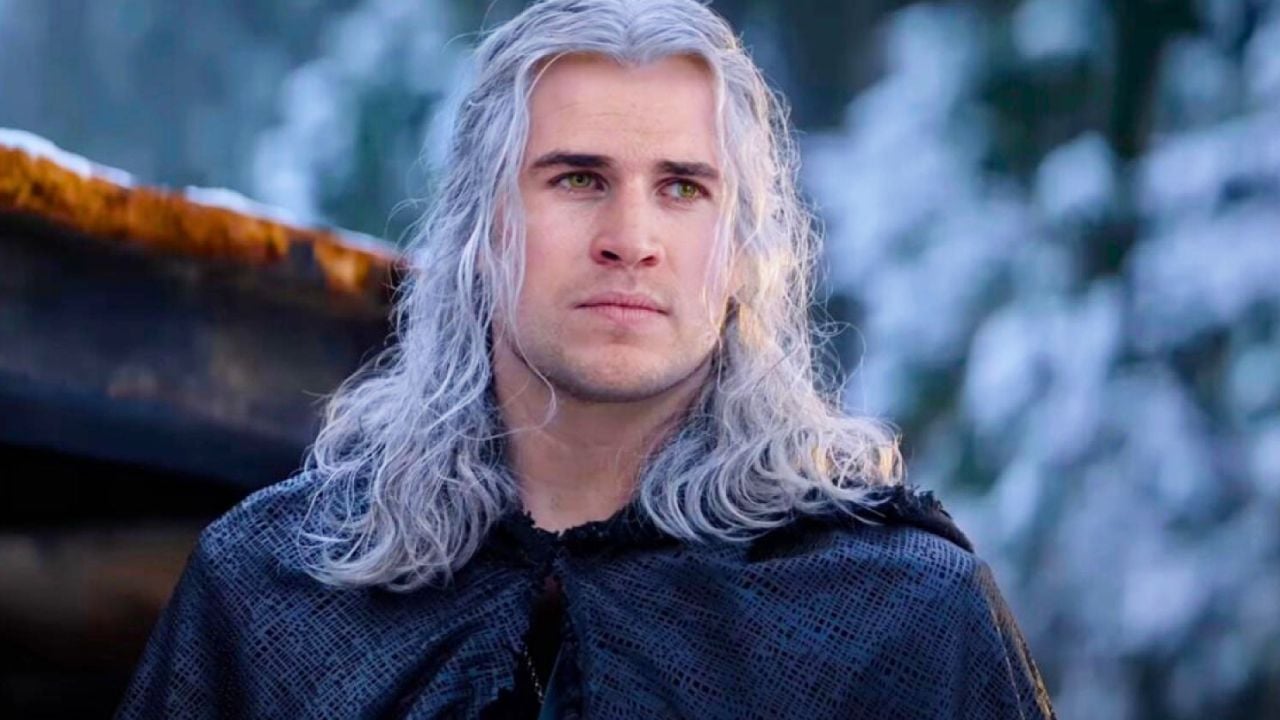

Precisely, a self-reflective character on the phenomenon of ‘Magic Mike’ conditions this third episode. Steven Soderbergh, responsible for the opening film, returns as director, having given the position to his assistant Gregory Jacobs in the sequel, ‘Magic Mike XXL’ —where, however, he was in charge of photography and editing under a pseudonym. What happened in the eight years that separate one feature film and another seems to have interested Soderbergh enough to finish what he started: originally planned, with writer Reid Carolin and star Channing Tatum, as a social comedy strippers masculine around the financial crisis and the subordination of all areas to economic relations (not only pleasure, but also pure affection, friendship and trust), the director would later see how ‘Magic Mike’ would become a talent show from HBO Max and a musical show in London.

This show is the starting point of ‘Magic Mike’s Last Dance’. According to Soderbergh in an interview with Total Film either in it podcast The Drop, Observing the concept of the work and the reactions of the spectators led him to “unexpectedly” consider this definitive delivery. Yes, along the lines of his collaboration with the former porn actress Sasha Gray in ‘The Girlfriend Experience’ (2009), the real life experiences of Channing Tatum as stripper teenager had served as the basis for Soderbergh in the first ‘Magic Mike’, Tatum’s own experience as director of the London musical adds more layers of referential reality to the third part, a film where its protagonist, Mike, is imagined as the director of a theatrical performance with strippers. The looks of the women, their participation in the show and, likewise, the economic mediatization of their desire is also part of the plot of this sequel, which has obtained the worst reviews (professionals and fans) of the entire saga.

The zombie apocalypse of the repressed people

Since his debut in 1989 with ‘Sex, lies and videotapes’, Soderbergh’s filmography has taken very different paths, largely due to the prolific nature of its author. As a good Steven Soderbergh report would conclude, the great variety of records exhibited throughout his almost 35-year career credits him as a restless filmmaker, with a left hand, an encyclopedic knowledge of the history of the genres and subgenres he touches and, with it, not a shred of naiveté in their approaches. Interestingly, the director has related ‘Magic Mike’s Last Dance’ to his ‘Ocean’s Eleven’ trilogy (2001-2007) by considering it a “process” film, where the narrative follows the plan that the characters have to execute; in this case, the London show. ‘Magic Mike XXL’, in fact, it ended in parallel to the first ‘Ocean’s Eleven’, with the heroes watching an artifice absorbed (the fireworks of July 4 and the lights and fountains of the Bellagio hotel, respectively) after consummating their feat.

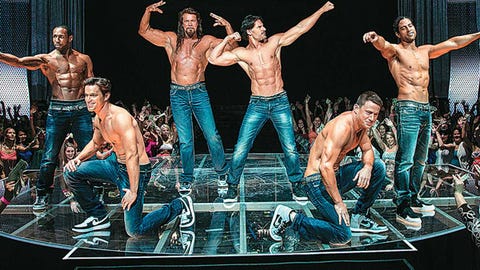

The idea of robbery cinema as a staging within another was the backbone of the franchise starring George Clooney, the smartest in the class. In the case of ‘Magic Mike’, however, it was in the second installment where it was fully embraced the narrative potential of the choreographies of striptease: after Soderbergh’s initial experiment with semi-documentary realism, in ‘Magic Mike XXL’ the screen was the canvas for the fantasy of unapologetic hedonism, where everyone enjoys dancing as a transcendental, cathartic and, in the mouth of one of the secondary, “healing” experiences.

Everything was positive, from the sexuality to the camaraderie between the leads. For journalist Chloé Cooper-Jones, who came to describe the proposal as “feminist” in an article in Vice, the film celebrated the existence of “men who communicate regularly with women without the promise of sex, who can celebrate a woman’s sexuality without implicit or explicit reproach, or who comfortably share their feelings without punching each other or hurling insults born of fear of gayness.”

In a scene of this third film, this festive desire is affected by talking about turning the swagger in front of the public into a “zombie apocalypse of the repressed people”, to which no one could resist. Despite these signs, ‘The Last Dance…’ takes a substantially different course. Following the classic structure of the saga, the character of Channing Tatum has a vehicular romance, here with an older woman (played by Salma Hayek) who becomes his benefactor after a striptease with a happy ending. Anyone who sees the saga as an empty game with the reversal of roles and sexual objectification can easily find new arguments here that reinforce them. For example, in The Conversation, academic Helen Warner pointed a problem of “male gaze” in his treatment of desire: “Rolling the bodies of men in the same way that [se hacía con] those of women does not translate into female empowerment. Rather, this kind of dehumanization reminds us how harmful patriarchy is to everyone.”

what women want

Every ‘Magic Mike’ movie, for better or for worse, has managed to surprise with an unexpected point of view, since none of the three episodes are very similar to each other. Unpublished in the saga, this end of the trilogy opens and closes a voice in off, that of the co-star’s daughter, who, throughout the narrative, covers the anthropological concept of dance and begins by explaining how it precedes human evolution. Another significant addition are the questions and setting of limits that, on this occasion, precede each dance: “Is it okay for me to play?”, “Do you want me to do this?”. If in the first film the issue of the difference between selling labor and selling the body hovered over the story, In Soderbergh’s approach to the experience of the female spectators in ‘The Last Dance…’ a curiosity about the tension between the limits of desire and the culture of consent seems to beat.

In the trial ‘Good sex tomorrow’ (2021, published in Spain by Alpha Decay), the writer Katherine Angel discussed the usefulness of the notion of consent as the beginning and end of all conversations about sex, considering that it placed on women the guilt of feeling dissatisfied: consent does not exclude having a bad experience. Angel proposed going further, demanding recognition of women as desiring subjects, demanding more from the other party. when it comes to understanding and reading their needs. In ‘Magic Mike’s Last Dance’, Tatum and his crew repeat that, for the play to work, they have to give women what they want and get into their head, an effort for which they have the invaluable suggestions of the character of Salma Hayek or the actress of the play. Not only that, there is also a remarkable number of contradictory scenes, where the characters say or ask each other for things that are different from what they end up doing, just like the main characters at the beginning.

After a pessimistic film and another euphoric one, Soderbergh has chosen as the conclusion to his saga the red herring of a romantic comedy. Musicals like ’42nd Street’ (1933), ‘A star is born’ (1937) or ‘All that jazz (The show begins)’ (1979) are in his DNA, but within that summa that forms the filmography of the director, where the texture of the digital image is what separates reality from fantasy, Soderbergh seems to wonder how much authenticity there can be in the processes (and gratification) of desire in a context dominated by capitalist logic, and to what extent that logic can be transcended. For Richard Brody, in The New Yorker, the answer is clear: “It is a cynical film about cynicism and artifice about artifice, where dance unites artists and businessmen with the power of the latter’s money. However, There is only one thing that cannot be faked, and that is love”.

Source: Fotogramas

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.