Erdogan’s 20-year legacy is at stake in voting against a powerful alliance in Sunday’s Turkish presidential and parliamentary elections.

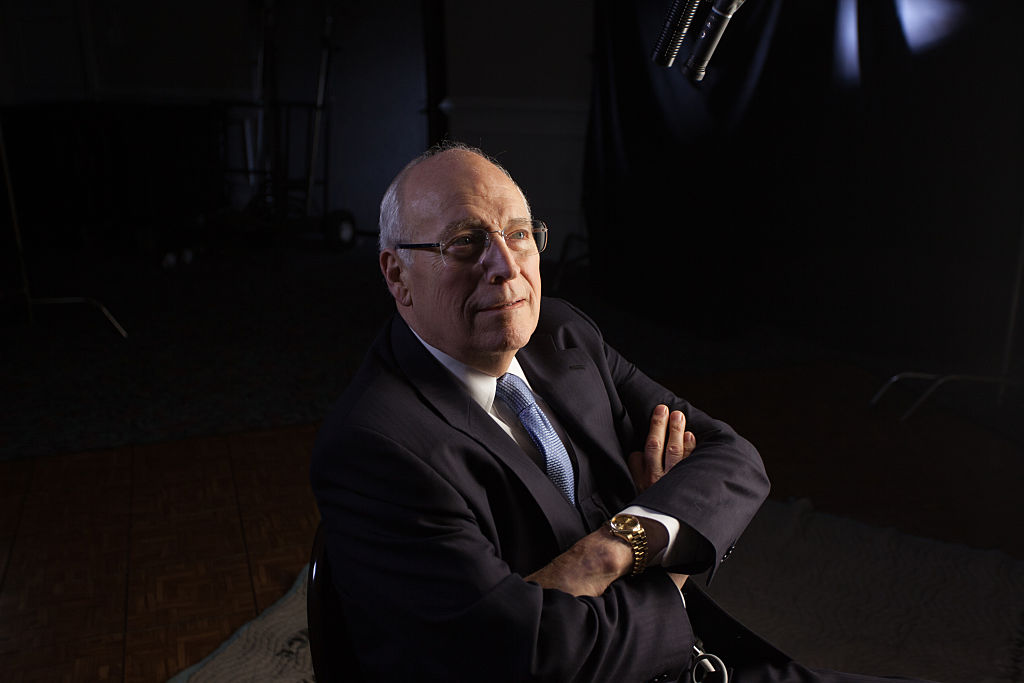

From humble beginnings, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has risen to political giant, leading Turkey for 20 years and reshaping the country more than any leader since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, considered the “father” of the modern Turkish republic.

However, his chances of extending his rule for a third decade hang in the balance as the country recovers from the most devastating earthquake since 1999.

The opposition accuses him of failing to prepare for disaster, Turkey being in a region prone to severe earthquakes, and of mismanagement of the economy.

rise to power

Recep Tayyip Erdogan was born in February 1954 and raised as the son of a Black Sea coast guard in northern Turkey.

When she was 13, her father decided to move to Istanbul, hoping to give his five children a better education.

Young Erdogan sold lemonade and sesame bagels known as ‘simit’, a type of bread popular in Turkey, to supplement his income. He attended an Islamic school before earning a business degree from Marmara University in Istanbul.

His degree has always been a contentious issue, with the opposition saying he didn’t have a full degree but something equivalent – a charge Erdogan has consistently denied.

Young Erdogan was also interested in football and played in semi-professional teams until the 1980s.

But his main passion was politics. In the 1970s and 1980s he was active in Islamist circles and eventually joined Necmettin Erbakan’s pro-Islamic Welfare Party.

As the party grew in popularity in the 1990s, Erdogan ran for mayor of Istanbul in 1994 and ruled the city for the next four years.

Erbakan, Turkey’s pioneering Islamic prime minister, served just a year before being forced to resign in 1997 by the military. And Erdogan has also clashed with the country’s staunchly secular authorities.

That same year he was convicted of inciting racial hatred for publicly reading a nationalist poem which included the lines: “Mosques are our barracks, domes our helmets, minarets our bayonets, and the faithful our soldiers.”

After serving four months in prison, Erdogan returned to politics. But in 1998 his party was banned for violating the secular principles of the modern Turkish state.

In August 2001 he founded a new Islamic party with his ally Abdullah Gul, the Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Erdogan’s popularity was growing, particularly among two groups: first, the pious Turkish majority who felt marginalized by the country’s secular elites, and second, those suffering from the economic crisis of the late 1990s.

In 2002, the AKP won the majority of votes in the parliamentary elections and the following year Erdogan was appointed prime minister. He remains party chairman to this day.

Three terms as prime minister

Beginning in 2003, Erdogan spent three terms as prime minister, presiding over a period of steady economic growth and winning international acclaim as a reformer.

The country’s middle class expanded and millions lifted out of poverty as he prioritized massive infrastructure projects to modernize Turkey.

Erdogan managed to reach voters from Turkey’s Kurdish minority even during his first years in power.

The rights of this population have improved and, after three decades of conflict, a new peace process was launched in March 2013, leading the militant group Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) to declare a ceasefire. But the deal only lasted two years and the prolonged cycle of violence returned.

In 2013, critics also began warning that Erdogan was becoming increasingly autocratic.

In the summer of 2013 protesters took to the streets, in part because of his government’s plans to turn a much-loved park in central Istanbul into a mosque and shopping mall, but also to challenge the more authoritarian regime.

Erdogan ordered the forced eviction of protesters from Gezi Park and the excessive use of police forces has unleashed an unprecedented wave of mass demonstrations.

This marked a turning point in government. To his detractors, he acted more like a sultan of the Ottoman Empire than a democrat.

Muslim revival

Erdogan’s party also moved to lift the ban on women wearing the headscarf in universities and public services, introduced after a military coup in 1980. The ban was eventually lifted for women in the police, in the army and in the judiciary.

Critics have complained that it has destroyed the pillars of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s secular republic. Though religious, Erdogan has always denied wanting to impose Islamic values, insisting that he merely supported the right of Turks to express their religion more openly.

However, she has repeatedly stated that a woman’s primary role in society should be “fulfilling traditional gender roles” which was “being an ideal mother and ideal wife” above all else.

She condemned feminists and said that men and women cannot be treated equally.

Erdogan has long championed Islamic causes and political Islam, groups ideologically close to Egypt’s repressed Muslim Brotherhood. Sometimes he even uses the latter’s four-finger salute – the raba.

In July 2020, he oversaw the conversion of Istanbul’s historic Hagia Sophia into a mosque, angering many Christians and secular Muslim Turks.

The building was built 1,500 years ago as a cathedral and transformed into a mosque by the Ottoman Turks, but Ataturk transformed it into a museum, a symbol of the new secular Turkish state.

path to the presidency

Barred from running for prime minister again in 2014 after reaching the three-term limit, he ran for the largely ceremonial role of president in unprecedented direct elections.

Erdogan planned to reform the office with a new constitution, which critics said would challenge the institution secular of the country.

But at the start of his presidency, he faced two major challenges.

His party lost its majority in parliament for several months in 2015 and the following year, on July 15, 2016, Turkey witnessed its first coup attempt in decades.

Nearly 300 civilians were killed blocking the advance of the coup plotters.

The conspiracy has been attributed to the Gulen movement, led by a US-based Islamic scholar named Fethullah Gulen.

His social and cultural movement has helped Erdogan win three consecutive elections, but the fall of the two allies has had dramatic repercussions on Turkish society.

After a coup attempt in 2016, some 150,000 civil servants were fired and more than 50,000 people arrested, including Kurdish soldiers, journalists, lawyers, policemen, academics and politicians.

This crackdown on criticism has aroused alarm abroad, contributing to the freezing of relations with the European Union (EU): Turkey’s attempt to enter the economic group has not advanced for years.

Discussions about the influx of migrants into Greece have exacerbated the malaise.

Erdogan narrowly won a 2017 referendum that granted him sweeping presidential powers, including the right to impose a state of emergency and appoint senior public officials, as well as intervene in the legal system.

international actor

During his leadership, Erdogan also gained prominence in international politics.

He built Turkey into a regional power, and his strong diplomacy angered allies, especially in Europe.

Although he headed a NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Western military alliance) country, Erdogan had close ties to Russia’s Vladimir Putin and positioned himself as a mediator in Russia’s war on Ukraine.

He helped broker a deal, opening a safe corridor for grain exports across the Black Sea and preventing its collapse when Russia decided to end its support.

He also kept Sweden and Finland pending his proposals to join the Western alliance.

He finally approved Finland’s membership, but kept Sweden out, claiming the country was home to Kurdish separatists and other dissidents he considered “terrorists”.

electoral setbacks

Many critics see the 2019 local elections as the “first blow” in Erdogan’s long reign, as his party lost in three major cities: Istanbul; the capital, Ankara; and Smyrna.

A narrow defeat in Istanbul to Ekrem Imamoglu of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) came as a major blow to Erdogan, who had been mayor of the city in the 1990s.

Now, Imamoglu is looking to extend that success nationwide by campaigning alongside the presidential candidate of a united opposition to Erdogan, Kemal Kilicdaroglu.

Criticism of the government’s lack of preparedness and slow response to a devastating earthquake that killed more than 50,000 people and left millions homeless in Turkey is one of the many challenges Erdogan is facing. Another is the dire state of the economy, with millions suffering from the cost-of-living crisis.

This Sunday, May 14, Erdogan will see his two-decade legacy at stake in a historic election against a powerful opposition alliance.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.