1978. At just 17 years old, Todd Haynes made his first film, Suicide, armed with a Super 8 camera. This 20-minute short film, with an ambiguous title, depicts a teenager trying to open his stomach in his bathroom.

After forty-five years, the filmmaker became a figure of American independent cinema. Recognized by the greats, from Kate Winslet to Christian Bale, the author has never stopped photographing the most vulnerable, the oppressed, and those living outside society.

This May 20th, in conjunction with the 76th Cannes Film Festival, Todd Haynes will present his tenth feature May December, starring Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman, in competition. Meanwhile, in Paris, the Center Pompidou will honor his work until May 29. AlloCiné’s opportunity to meet him to immerse himself in his world.

AlloCiné: Your first short film, Suicide, is a very striking work that lays the first foundation of what your cinema will be like. How do you make a movie like this at 17 years old?

Todd Haynes: I wrote it when I was 15 years old. It was for a thesis as part of an exam. We should write a myth about the hero and set him in the city of Oakwood. I took a red pen, a blue pen, a black pen and a pencil. I started writing this story by using different colors, where each color corresponded to a different voice in the character’s head.

All this turned into a kind of montage that took shape. The first line of this story was colored in red: “So I began to cut myself into pieces, carefully and thoroughly.” It is the suicidal fantasy of a child, a young boy trying to cope with pain and difficulties at school. But it’s also, of course, a true metaphor for filmmaking and editing.

“Suicide”, Todd Haynes’ first short film in 1978.

I wanted to show that the creative process is not all rosy. You are working with all your senses and need to dig into the darkest part of you. And I think that was partly inspired suicide.

It took us two years to make, from writing to sound. The story is much longer, but it got pretty crazy. We ended up mixing the film in 35mm even though we shot it in Super 8. It was an amazing experience. And that fueled my ambition to make other films.

Do you remember your parents’ reaction to your film?

My father is in the movie! He is the one who hits my little brother. My parents have always been an integral part of my process. When I was younger, I did a Romeo and Juliet movie at the age of nine, and my dad took care of the camera while I played all the parts. When I was Romeo in one shot, fighting with a sword, he was the other sword. My father was always there and so was my mother. They supported me a lot.

You’re talking about the kick scene. This image appears in many of your works. Where does this obsession with corporal punishment come from?

It was a trip down memory lane and childhood fantasies like that dream sequence at the end of Dottie Gets Spanked that ends with some crazy montage. This is a kind of orgasm. I dreamed about being spanked at the age of 4, and there was an erotic component to it, I know.

Excerpt from “Dottie Gets Spanked” by Todd Haynes.

When I remembered that dream, my grandmother, who was into art, had all these anatomy books in her studio, and I literally saw a montage of all these anatomical pictures that you see in Dottie Gets Spanked. So these come from childhood memories, but they combine a lot of interesting ideas and thoughts that made me look into the subject of kicking.

In 1991, you made your first feature film, poison, which follows three independent stories. Even before its release, the film is singled out by the American Family Association, a very conservative organization. You are accused of “propaganda” of homosexual sexual practices. Did you perceive this controversy as an obstacle, or rather an opportunity to make your film more visible?

It didn’t bother me, but I also didn’t care enough to pay more attention to the film. I wanted people to talk, ideally, about the film itself, not the controversy. But the controversy showed what the film was hinting at.

It depicted a divided society designed to isolate different people and make them outcasts, outsiders, problems. And you have to overcome these prejudices to solve the AIDS epidemic, because it has become a way for society to penalize and victimize people who are already marginalized.

We are all poisoned by society in some way.

What do you think about this new wave of Puritanism that can be seen in the United States as well as in Europe?

In any case, there is much freer hate speech in the United States than ever before, and especially by the far right. This is a small part of our country that is deteriorating. They just get a lot of attention. And of course the Trump era has contributed to that, but there are also a lot of people who are struggling.

A voice is being heard against this hate and I am only optimistic. Trump’s moment, despite the fact that he remains the only possible Republican candidate for the presidency, did not work. Therefore, it is an endangered minority that will age within the population.

One of the main themes of your cinema is about illness. Many of your characters are in poor health. You are approaching anorexia (Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story), misuse of the chemical industry (Dark waters), allergy (Safe)…

There’s this idea of toxicity, poison, environmental issues, social poisoning, and that we’re all somehow poisoned by society. But what was useful and amazing about Jean Genet, who was the inspiration for my first film Poison, was that he talked about the fact that we all have poison in our hearts. So the poison just doesn’t charge us.

In Dark Waters, Todd Haynes sheds light on the toxic drifts of the chemical company DuPont.

We also have feelings full of poisons. We poison ourselves. There is poison when we expel all our discharge, phlegm, urine, pus, and all that the body produces, and immediately say to ourselves:Oh, it’s not my part! It’s disgusting.“It’s an amazing contradiction because it’s part of us.

Of Safe that far from heavenwith you Carol, you highlight complex female characters who don’t hesitate to go against society’s norms, even if it means isolating themselves from the rest of the world. So is your film May-December. What excites you about his characters?

It’s hard to put them in one category because I see all the differences from story to story. And not all of them are necessarily strong women. They are also vulnerable and passive or diminished by the conditions they face. They don’t really solve the problems they face. At least that’s how movies like this are Safe and far from heaven.

These two films are directed by Julianne Moore. He is your favorite actor. How would you describe his approach to the game?

Julianne Moore There is a woman who has worked with extraordinary actors from all walks of life, but understands the camera lens like no one else. He knows how to step aside to let the audience come in and do their thing by filling in the gaps.

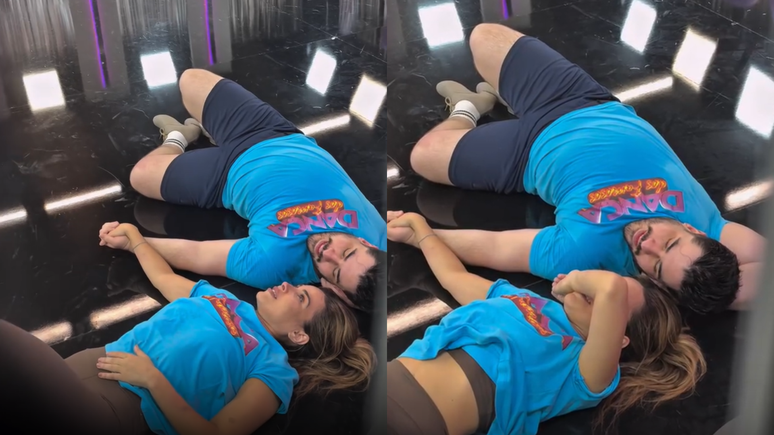

Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore in May in December.

That’s where the real emotional experience comes from and what the audience does. And you have to give the audience the space to do that, give them the tools, and sometimes take the tool away from them so they can rely on it more. And this is something Julianne Moore knew intellectually and intuitively as an actress at an early age.

Music is very present in your work. You made movies (A velvet gold mine, I’m not there…), Documentary (Velvet Underground) on musicians and even on Sonic Youth music videos. What fascinates you so much about the figure of a rock star?

What I love about them, especially Bob Dylan and David Bowie, is how they allow their music, their stardom and their creativity to continue to open up questions about self and identity and continue to disturb us in the most interesting ways.

In fact, especially in the glam rock era, which allowed young audiences and young people to feel comfortable not knowing who they were and to find out who they were, to change, to dress a certain way and a different way. This instability, this sense of radical instability, which is actually the norm rather than the exception or bad choice, is what these artists perpetuate.

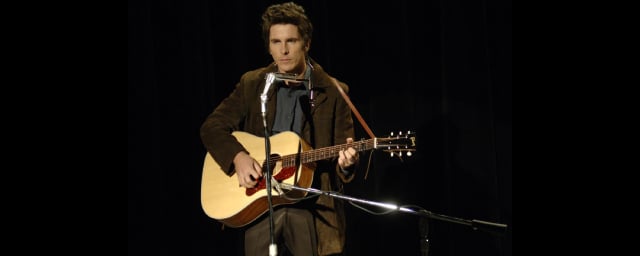

Christian Bale as a variation of Bob Dylan’s “I’m Not There.”

As for Bon Dylan, he did it out of a sort of personal necessity to continue making art. And his fans were very disappointed when he picked up an electric guitar and he was no longer a folk singer or a protest singer. And then he took it even higher when he became a Christian again. You are completely confused about who he is and what he believes.

And in a way, that means he’s alive. Old cells die and are replaced by new cells. It is a constant process of mutation. He made it the guide of his creative life.

Interview by Thomas Desroches, Paris, May 10, 2023.

The Todd Haynes retrospective takes place at the Center Pompidou, Paris, from May 10 to 29, 2023.

Source: Allocine

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.