Those responsible for the recent military coups in Africa are playing on anti-Western sentiment as much as possible.

The recent wave of military coups in Africa is a wake-up call for the whole world.

Since 2020, the army has seized power in several countries on the African continent: Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Niger and, most recently, in the oil-rich Central African country Gabon on August 30.

In Chad, after the president died in battle against rebels in 2021, the military ignored the constitution and simply handed over power to his son.

Also in 2021, the Sudanese army ousted the prime minister – whom they themselves appointed – and decided to lead the country independently. And in 2023, conflicts erupted between two rival junta groups, claiming thousands of lives.

Several other African countries have seen failed coup attempts (The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau and São Tomé and Príncipe). In Sierra Leone there was a military conspiracy that was unsuccessful.

In some countries, the military junta has announced that it will hand over power to elected governments, but only after a transitional period, which is expected to last several years. And there is no guarantee that this period will not be extended under the pretext of countering jihadist attacks, as in Mali or Burkina Faso, or to allow for the transformations deemed necessary by the military leaders.

More and more influential military officials are deciding they can shape the future of their countries, together with groups of supporters.

Rule or exception?

In the history of Africa, especially in most of the French-speaking countries of the continent, it is not uncommon for coups to occur.

But in the last three years its incidence has increased significantly, compared to the period between 2000 and 2020, characterized by the predominance of democratically elected governments and high rates of economic growth in most African countries.

It was at this time that the formation of the African Union took place, which brought a wave of optimistic predictions about the future of the continent.

But the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have had strong social consequences. Inflation has driven up food and fuel prices, exacerbating existing economic problems and political contradictions in African countries.

In Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, for example, jihadist groups have been activated, making West Africa, since 2012, one of the most unstable regions on the planet. In Guinea and Gabon there have been allegations of fraud and authoritarianism by elected presidents.

A significant factor in most African countries remains the population explosion. The number of young people is constantly growing and there are not enough jobs. As a result, support for elected governments was not enough during coups, while central city squares filled with disaffected youth in support of the military.

anti-Western sentiment

Those responsible for the military coups made the most of anti-Western and especially anti-French sentiments.

Almost all the countries that have suffered coups are former French colonies. In them, France exerted a large and lasting influence within the concept of “Françafrique”, or “French Africa” - a system of strong political and economic ties with influence over the domestic and foreign policies of African countries.

During the Cold War, France supported the change of power in some African countries. But even more recently, French presidents – notably Nicolas Sarkozy, who held the presidency between 2007 and 2012 – have been accused of meddling in the internal affairs of some African nations, particularly with France’s active participation in the war in Libya against Muammar Gaddafi, in 2011.

In recent years, France has been trying to build a new image among African countries, but there are widespread accusations of practicing “two weights, two measures”.

President Emmanuel Macron, for example, has condemned the coups in Mali and Niger, whose militaries have tried to sever relations with France. But the French representative has remained loyal to the military leader of Chad, Mahamat Déby, who is trying to maintain relations with Paris.

The military junta in Mali and Burkina Faso has actively begun to establish relations with Western opponents, primarily Russia. And the Burkina Faso junta, led by Captain Ibrahim Traoré, has also announced its desire to establish close relations with China, Iran, North Korea and Venezuela.

Army supporters use France and other Western countries as a scapegoat. They accuse them of resisting change and causing all the problems.

The reaction of the West

The July coup in Niger – a country rich in uranium and oil in West Africa – was the litmus test of the reaction of the West and of the democratic countries of the African continent.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), led by Nigeria, has issued an ultimatum to the military junta of Niger, demanding the return to power of elected president Mohamed Bazoum and threatening to send a unification military contingent to the country.

The deadline for the ultimatum has long passed and the threat of military intervention has not materialized. Consequently, the only way to fight the military regime remains through the imposition of economic sanctions. And failure to comply with the vehement threats served to convince ambitious militaries that establishing dictatorships in the region would not meet with much resistance.

In fact, the Nigerian military junta has established mutual assistance agreements with the armies of Burkina Faso and Mali, allowing them to send troops to their territory in case of intervention by ECOWAS. And Niger’s military rulers are now demanding that France withdraw its troops (there are 1,500 French soldiers in the country) and the French ambassador to the African country.

So far Paris has ignored the requests because the military junta is not a legitimate government.

The tension and uncertainty surrounding Niger has meant that the worst predictions that successive military coups would cause the collapse of democratic regimes in Africa, like a domino effect, have partially come true.

Of course, in some African countries the military has never been in power, such as in Senegal, Tanzania, Kenya and many others. It is difficult to imagine military coups in these countries.

But in many others, ambitious officials may not be able to resist the temptation to seize power, especially in French-speaking countries with their fragile political institutions and history of past coups.

The coup in Gabon

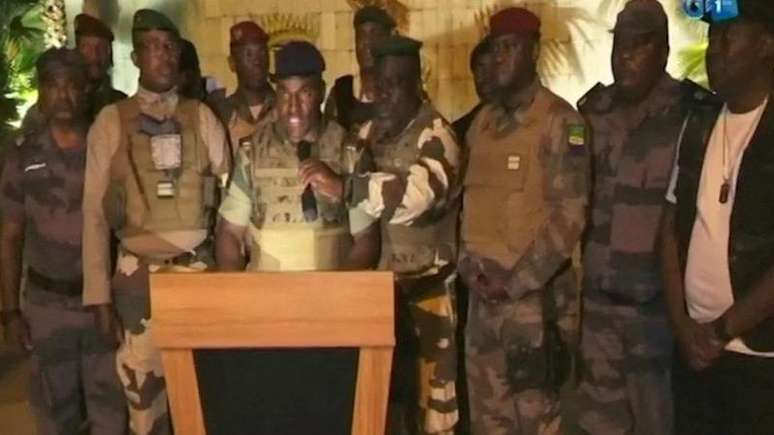

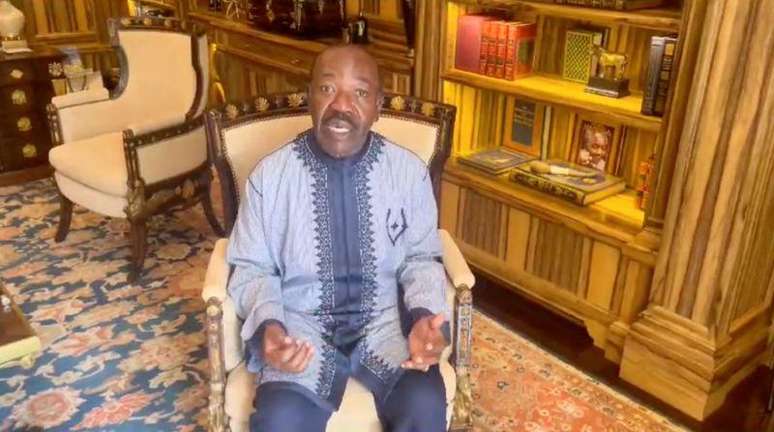

Even the most recent coup in Gabon can be considered a “palace coup”. After all, the military-created “Committee for the Transition and Restoration of Institutions” was headed by the cousin of ousted President Ali Bongo, the commander of the Republican Guard, General Brice Cloter Oligi Ngema.

Ngema was not born by chance. She was an assistant to the deposed leader’s father, Omar Bongo (1935-2009), who was the country’s president for 42 years.

After Bongo’s death, Ngema was neglected by his son for a time and sent into “diplomatic exile” as a military attaché. But he returned to the country, in a high position, in 2019.

It’s no surprise to see crowds celebrating the president’s removal from power. After all, the Bongo Dynasty ruled Gabon for 56 years.

The opposition has repeatedly accused the then president of electoral fraud and inheritance of power. But, as is the case with other military juntas, Gabon is also likely to have a transitional government that will delay the next elections for as long as possible.

And if Western powers demand the return of democratic government, the military could start looking for new international partners.

What happens next?

The establishment of military regimes in many African countries could have catastrophic consequences for the continent.

Military councils may use budgetary funds and borrow internationally without proper corporate oversight. They can also more easily silence journalists and their disgruntled opposition.

As Western powers and international financial institutions are unwilling to lend money to regimes deemed illegitimate, the military will continue to seek military and financial support from Russia and China, in exchange for access to natural resources and support for its foreign policy .

Mali, for example, which previously abstained from voting on resolutions on Ukraine’s integrity, now voted against a similar resolution in February 2023.

But Russian assistance hasn’t helped Mali, or Burkina Faso, solve its internal security problems. The year 2022, for example, was the deadliest year in these countries in terms of victims of jihadist attacks, according to the NGO Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

As a result, African countries that have fallen under military rule could eventually see their economies and political institutions further weakened, coupled with a host of unresolved security concerns and an even greater desire among young people to leave their jobs. village.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.