Sex in America is always on the mind. To admit this is superficial nonsense, but sexual politics are everywhere, especially in film and television. In the past year, several writers have discussed this topic: they have discussed the death of the sex scene and heightened the pleasure of seeing a woman come. The internet struggled and agreed to disagree with the male gaze, the female gaze, and other arguments about the sex scene’s target audience.

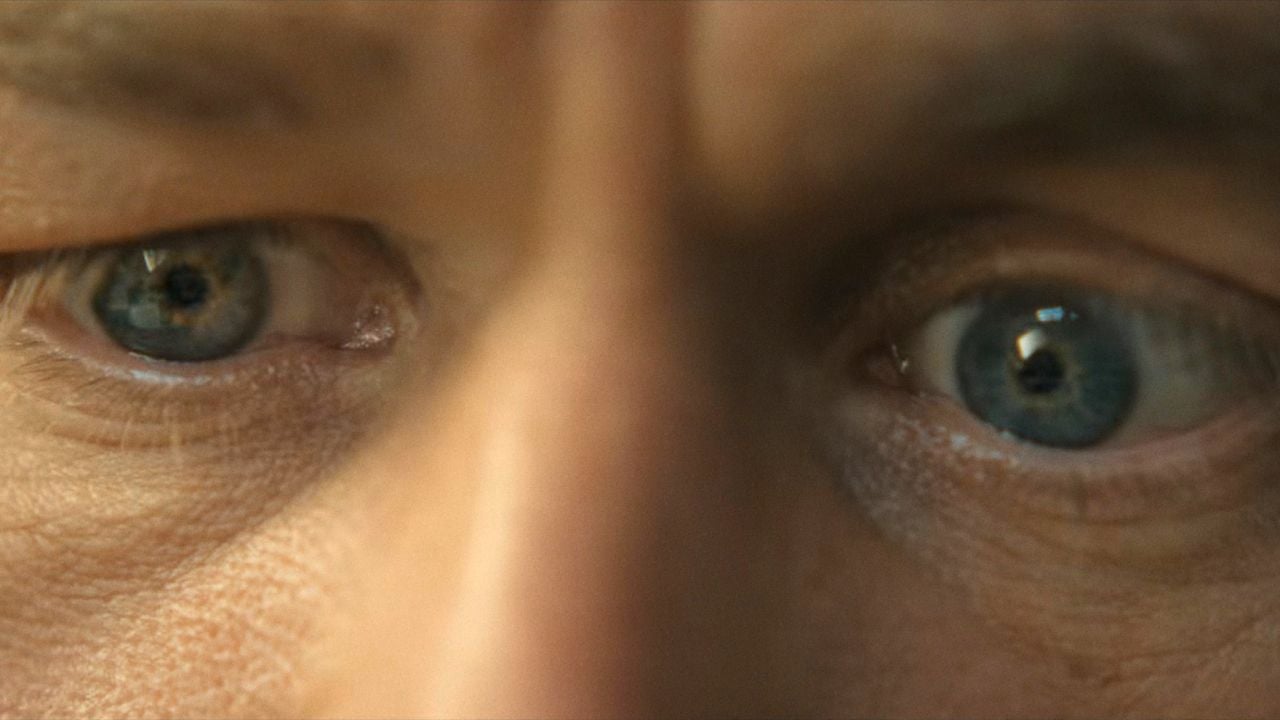

Behind these investigations and dialogues hide simple mechanical questions: What does it mean to invent an erotic state of mind? What gives the film a sensual aura? How is the sex scene created? Gift from Christy Guevara-Flanagan Body parts It is that, at least in part, it gives us some answers to these questions.

Body parts

A clever film that draws some mind-boggling conclusions.

Event: Tribeca Film Festival (Featured Documentary)

Directors: Christy Guevara-Flanagan

1 hour 26 minutes

to the best, Body parts Lower the curtain creating a sex scene. Interviews with stuntmen, visual effects experts and intimate relationship coordinators reveal the details behind the most painful cinematic moments. But the film, unfortunately, does not stop there. He scatters a bunch of giddy topics, jumping to conclusions about the politics of pleasure, the #MeToo movement, and a triumphant, unbridled narrative of women’s empowerment.

The film opens with Linda Williams, filmmaker and author. sex detectionWe’re talking about the role the media plays in shaping our relationship to sex. The way the films portray libidinal activities certainly directly conveys the prevailing understandings and conversations about desire and pleasure. He looks at the sexiest period in cinema (1920s and 1930s) and describes how that changed in 1934 with the introduction of the Hayes Code. Suddenly, evidence emerged of what was considered appropriate for society, and sex was presented as a fatal rather than pleasurable act. Williams’ wit and analysis inform the film, allowing her to move from broader ideas to outlining specific sex scenes.

Interviews with actors such as Rose McGowan and Jane Fonda and various directors and screenwriters illustrate these scientific pieces in more modern anecdotes. The foundation show is the most useful and interesting way to understand how Hollywood has treated sex for decades. The star talks openly about moments early in his career when he was under pressure to come out on the line so he wouldn’t risk ending his career. Other actors share similar stories of coercion. Many find the stories of being kicked out of the sex scene disturbing.

These disturbing testimonies and experiences are not limited to white, non-disabled, gay and straight women. Body parts He is tasked with examining images of sex, or lack thereof, for people of race, ethnicity, gender and disability. Media scientist Stephen Dunn takes viewers back to the era of Blaxploitation films and explains how he was driven by the notion of black sex and sexuality, while director Angela Robinson briefly touches on the lack of stony images of desire. Some of the analysis in this review takes a snap and you might miss what I think is related to the weird nature of the topic.

Money is a hinged line Body parts. Guevara-Flanagan takes viewers into the industry of the sex scene, speaking to different participants. Body doubles are usually a group of unrelated actors who support the performers during sex scenes. Shelley Michelle, one of the two interviewees, describes the profession with harsh words, comparing an audition to a “cattle bell”. Individual parts of your body are evaluated with clinical accuracy, and if you choose to participate in the film, there is little chance of getting credit. A visual effects specialist talks about the process of cutting and inserting (placement of the actor in his anonymous body) used in some of the scenes and describes in relative detail how much the actors ask him to clean faces and bodies. The doctor basically offers intimate relationship coordinators at work, showing how a sex scene (or rather, consensual) is constructed. Various directors and filmmakers talk about how they get these scenes.

Body parts He shudders as he transitions to the #MeToo movement and the Hollywood consensus. From the moment of its opening, the Doctor reflects an optimistic ending, eventually forcing him to invade this area with an unrealistic sense of optimism. Accusations of men like James Franco and Harvey Weinstein are considered substantially, as is the fact that these two men are just the tip of the iceberg in an industry deeply rooted in white supremacy and virginity. So it’s strange when the bottom third of the doctor opines that all this will change if more women are employed.

This is a peculiar spot where you have to land before him after submitting all the information. If there’s one thing we’ve learned in recent years, it’s that uncritical calls for more representation don’t cure industries that are plagued by broad structural problems. but Body parts It’s a smart film and a helpful introduction to the big questions about sex and cinematic depictions of desire. I wish your conclusions were more subtle.

Source: Hollywood Reporter

Emily Jhon is a product and service reviewer at Gossipify, known for her honest evaluations and thorough analysis. With a background in marketing and consumer research, she offers valuable insights to readers. She has been writing for Gossipify for several years and has a degree in Marketing and Consumer Research from the University of Oxford.