The demolition of Kowloon marked the end of a unique way of life in Hong Kong: it was a city with no laws and minimal services, but with a strong sense of community.

The demolition of Kowloon Walled City 30 years ago marked the end of a unique way of life in Hong Kong.

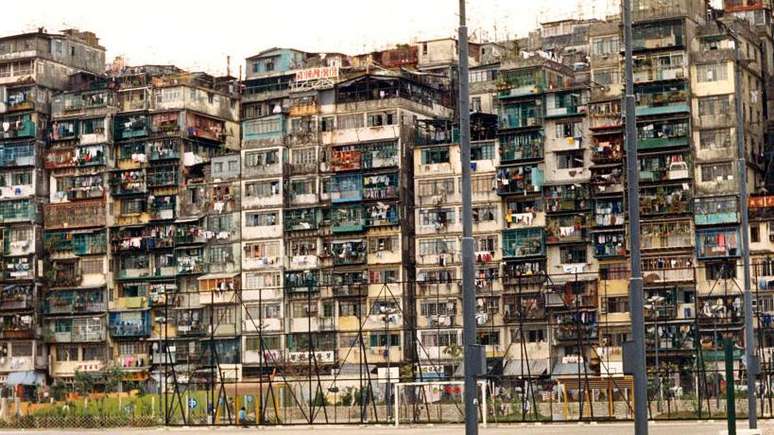

A few acres of land, left as a sort of enclave in British-controlled Hong Kong, at a whim of the colonial administration, became one of the most densely populated places on the planet.

While the rest of Hong Kong was a British colony, the 2.7 hectares of the ancient walled city remained nominally under mainland Chinese control.

This idiosyncrasy has turned this small piece of land into a lawless area.

It’s been 26 years since the sovereignty of Hong Kong was transferred from the United Kingdom to China and 30 years since the demolition of Kowloon, but the people who lived in this crowded city still remember the special feeling of community.

It was a place of crime, but also of cooperation.

Your origin

The history of the walled city dates back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when a military post was established to handle the salt trade in the region.

Centuries later, in 1842, Hong Kong Island was ceded by the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) to the British in the Treaty of Nanjing, but the walled city of Kowloon remained under Chinese control, home to around 700 people at the time.

China believed it needed to be present in the then British colony and considered using Kowloon as a control point to oversee the region, but over time abandoned this idea.

Therefore, with the British policy of non-intervention, the city was left in a legal vacuum, with no authority to take responsibility for it.

With the turn of the 20th century and the outbreak of World War II, Kowloon became home to immigrants and illegal groups seeking to escape the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, which began on December 25, 1941.

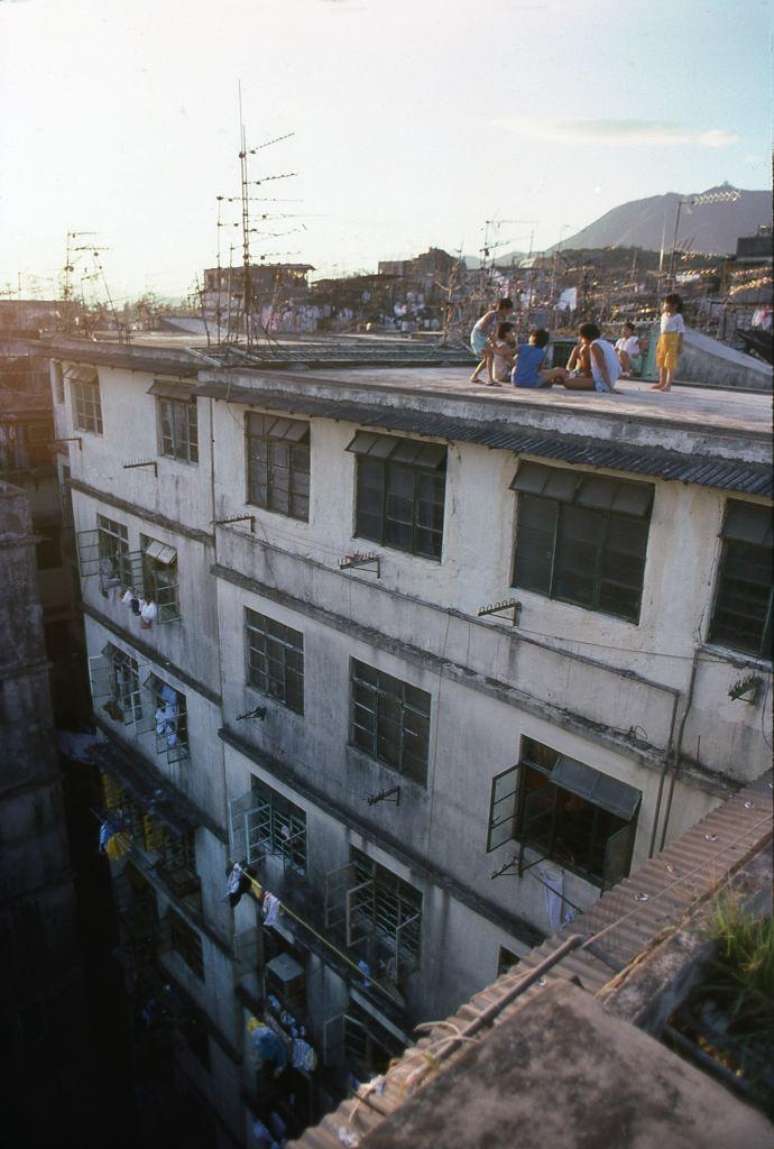

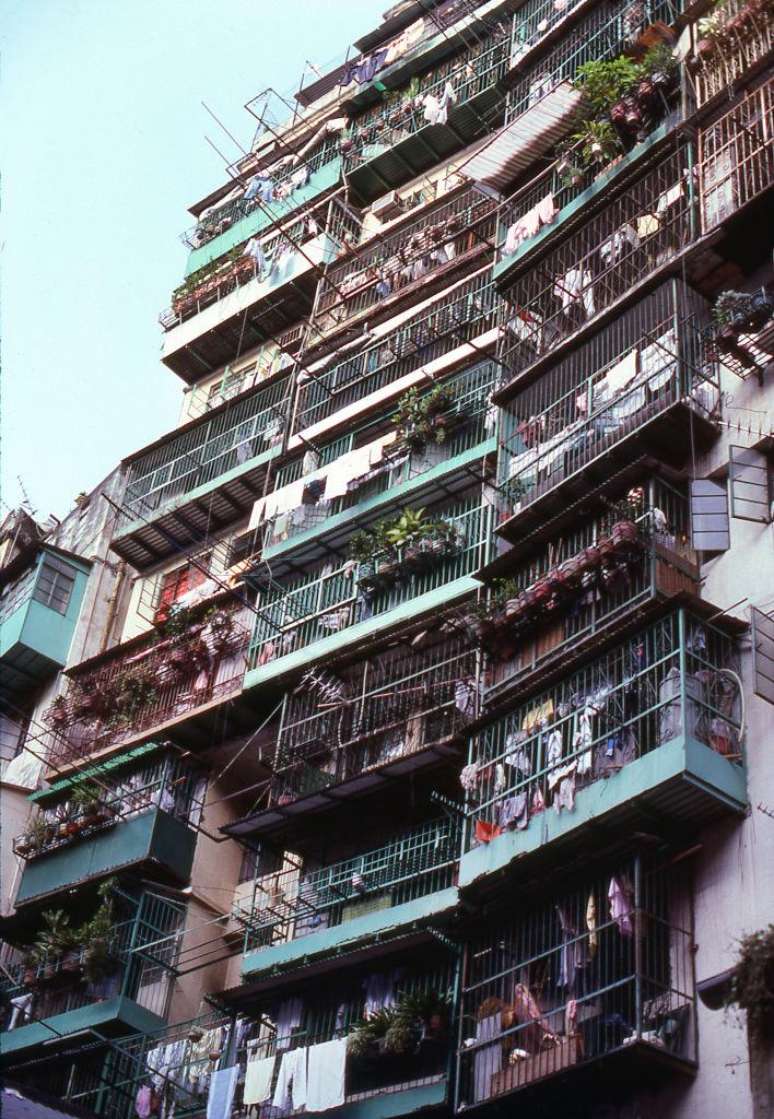

After the surrender of Japan, the city, now without walls, continued to grow, but, unable to expand horizontally, it expanded vertically.

From 17 thousand inhabitants during the Second World War it reached 50 thousand at the end of the 80s, becoming the city (within the city) with the highest population density in the world.

14-story buildings stacked on top of each other, like a living organism.

Opium dens, brothels and casinos run by criminal gangs dominated the area. The police, health inspectors and tax collectors were afraid to enter.

What was life like in there?

Because it was never handed over to the United Kingdom, residents often felt that the city truly belonged to China and that the Hong Kong government should leave them alone.

The result of all this was one of the most emblematic marginal neighborhoods in history.

Kowloon was rife with crime, prostitution and drug use, but there was a great closeness between those who called the place home.

Together, the residents have resisted the Hong Kong government’s attempts to expel them for decades.

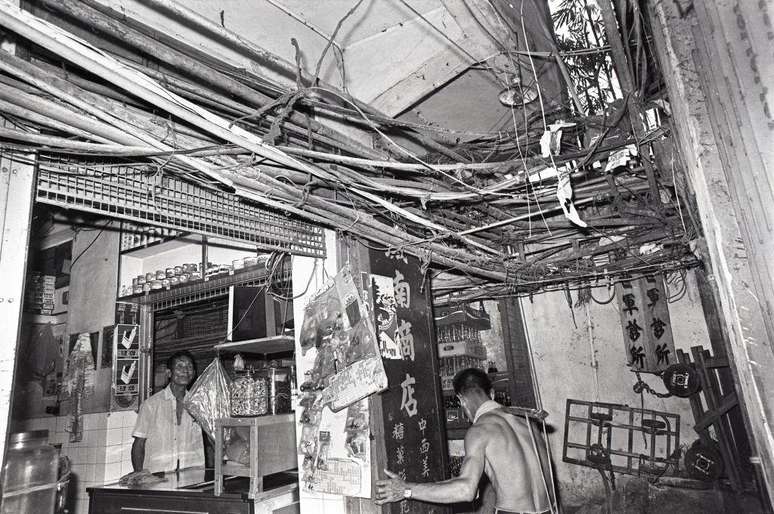

Chinese traders, healers, and self-taught dentists, along with criminals, fought to keep the city alive.

With 300 interconnected skyscrapers, all created by a single architect, Kowloon was truly a den worth seeing.

“The only reason we moved to Kowloon Walled City was because it was the only place we could afford,” recalls Albert Ng, who grew up in Kowloon Walled City after his family moved to Hong Kong from mainland China in the 70’s.

“Kowloon City was famous for things like prostitution, gambling and drugs. When I went to school in these dark alleys, I saw people doing illegal business and I discovered that they were up to something,” Ng points out in the radio program “Witness History”. from the BBC.

“City of Darkness”

“The first thing you feel is this warm humidity that has a strong smell. It’s disgusting. When you enter, you really feel like you’re entering the dragon’s throat,” recalls urban planner Suenn Ho, returning to Hong Kong, where she grew up , to study Kowloon Walled City with a scholarship in 1991.

“The first day is still very vivid in my memory. I had all my cameras and video recorders. It actually wasn’t very clever, because I really stood out as an outsider,” comments fascinated Suenn Ho, like many other urban planners, for the unique development of Kowloon.

The lack of control in the city has led to the flourishing of all kinds of illegal activities.

“The British officials couldn’t do anything, because every time they tried to act, the Chinese government told them not to intervene, because that was their territory. But China is far away. So eventually the opportunists emerge and start doing things illegal, taking advantage of the absence of law”, adds Suenn.

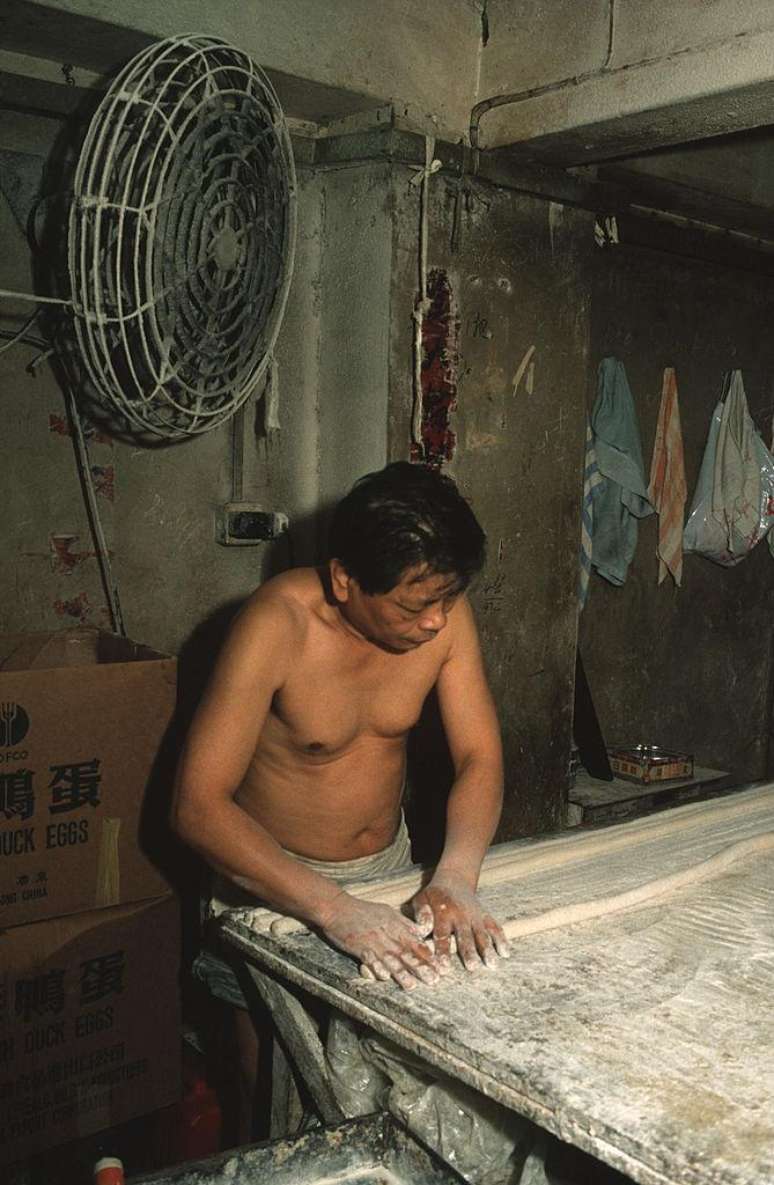

The Walled City’s few blocks attracted not only gangsters and drug traffickers, but also factories selling counterfeit luxury goods and unregulated food companies that produced fish balls and dumplings for Hong Kong restaurants.

“There were also many doctors and dentists, very many dentists. All these professionals worked illegally, because they could not practice in Hong Kong due to their poor knowledge of English and the inability to take the assessment test,” Suenn explains about it a practice that has led Hong Kong residents to seek treatment in the Walled City.

“When I grew up, my family had a maid there, and one day she told me that she had a toothache and that she was going to the walled city to have it removed. When she returned home and I asked her if they had pulled it out the tooth, she replied, “Well, actually, they took out the wrong tooth.”

“They lost the tooth? What happened?” I asked, and she said, “Don’t worry. They missed the tooth and then realized they had to take the other one out, so they took the other one out too, but they just charged me a tooth.”

“He thought it was a great deal,” Suenn says.

Although the physical walls of the Walled City had been torn down after World War II, it was still possible to clearly identify where the Walled City was located, as no building regulations existed within its perimeter. The city grew to fill all available space.

“Within the Kowloon Walled City, all the buildings were stacked on top of each other. There was almost no space between one building and another,” recalls Albert Ng. At the height of its population, between 35,000 and 50,000 people lived on an area of just 2.7 hectares.

Aerial photos from the time show the walled city towering above the surrounding suburbs, a huge mass of organic-looking buildings, as if from a science fiction film.

“But we really had fun. On the terrace we jumped from one building to another. The buildings were half a meter apart from each other,” recalls Albert Ng.

“Only the best pilots could fly to Hong Kong, because when you started landing, you thought if you could open the window of the plane, you could touch the clothes hanging on the clothesline on the terrace,” jokes Suenn Ho.

“We played flying the kite on the terrace and tried to guide it so that it would collide with the planes, but obviously we couldn’t,” adds Albert Ng.

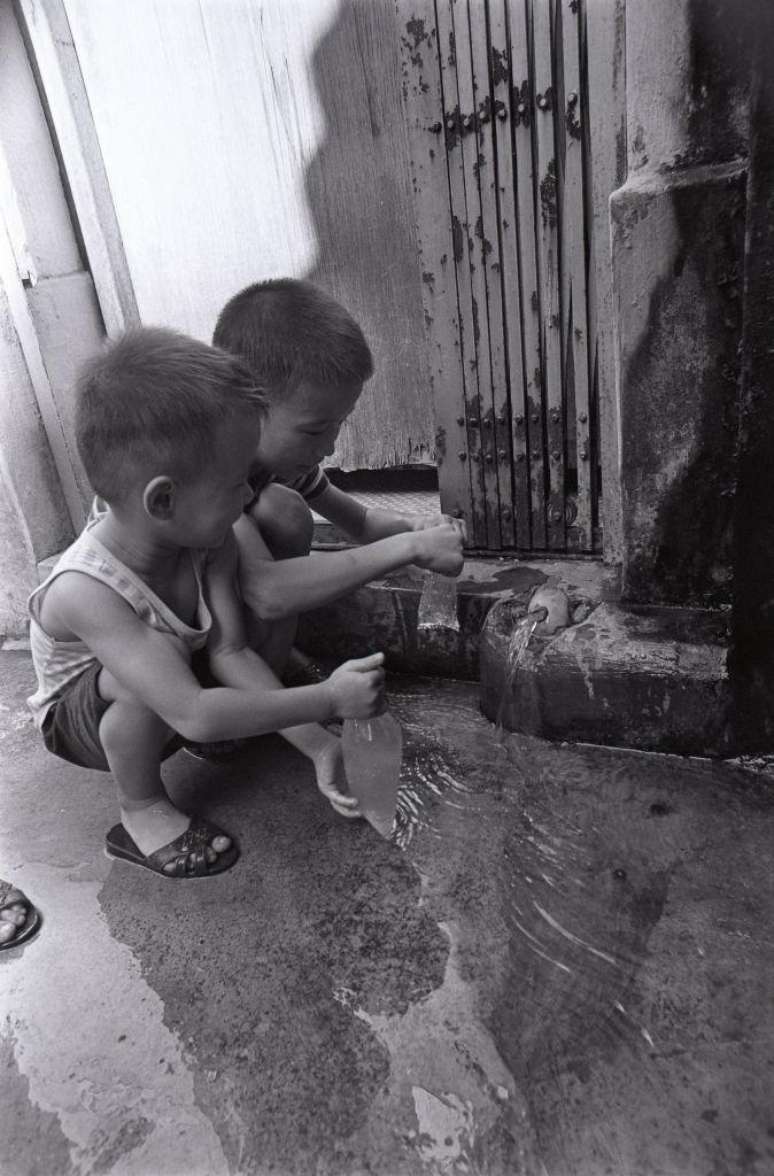

Because the city was built in such an anarchic manner, Albert Ng and his family did not have access to basic services available in other parts of Hong Kong.

“The environment was very dirty, with open sewers visible everywhere, and we had no running water in the house. Our walls were always damp and moldy. There was dirty water coming from outside the building and as a result I I contracted tuberculosis twice when I was in high school,” says Albert Ng.

Living so close to each other has given residents a strong sense of community.

“There was a lady from Shanghai who lived right across the street from us, and every time she made Shanghai dumplings, she would put them as best she could in a plastic bag or maybe in a bowl, tie it to a stick and pass it to us , and vice versa. When we did something, we passed it on to her. So I think living within the Kowloon Walled City provided a very, very good community life,” says Albert Ng.

Demolition of the city

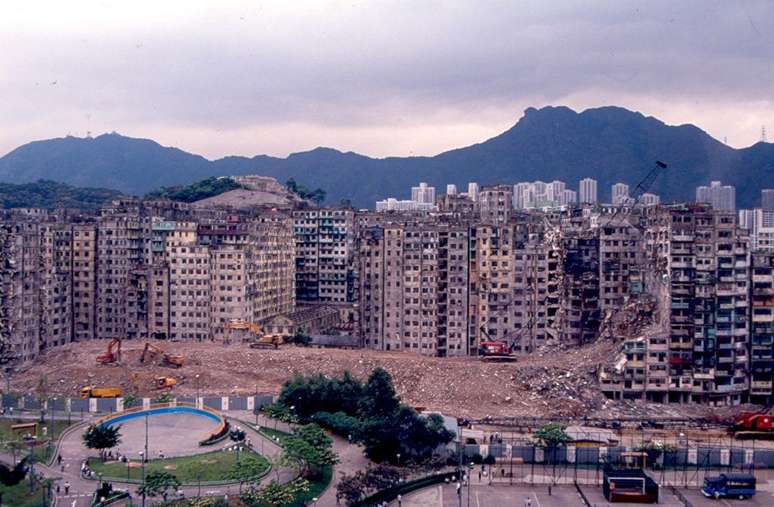

In 1987, anticipating the return of Hong Kong by the British to China in 1997, the Chinese and British governments decided it was best to demolish the walled city.

“When I heard the news that the government was going to demolish it, I was very happy. Living in what could be the worst city in the world was so difficult that, honestly, I couldn’t wait to move,” explains Albert Ng.

By the time Suenn Ho was conducting her research, much of the area had already been cleared. She had dinner with some friends on the last night at home before the eviction.

“It was a great emotion, because at the end of the dinner, the great-grandmother was sweeping the floor and the daughter, very angry, said: ‘Tomorrow morning they will take away our house and you are here sweeping the floor.’ ?’ And the great-grandmother said calmly: “You know, I have lived here for a long time, and if I have to leave my house tomorrow, I still have to clean it. This was my home,” recalls Suenn Ho.

Kowloon currently hosts a public memorial park with a lake.

Demolition finally began in March 1993. The area is now a public park.

“I feel like our life has started again and everything will be fine from this moment on. But, to my surprise, I still dream of returning to Kowloon. It is a precious part of our history. Like it or not, it was my home,” she says Albert Ng, who is now a pastor at a church in Hong Kong.

*Suenn Ho and Albert Ng spoke to Lucy Burns for the BBC’s ‘Witness History’ programme, which first aired in 2020. You can listen to the full program in English here.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.

![Here it all begins in advance: Carla discovers her true colors!… What awaits you in the week of October 27 – October 31, 2025 [SPOILERS] Here it all begins in advance: Carla discovers her true colors!… What awaits you in the week of October 27 – October 31, 2025 [SPOILERS]](https://fr.web.img4.acsta.net/img/1a/c9/1ac9c60c3279849c2babe78e208ce4ff.jpg)