Discover the surprising connection Sigmund Freud had with the region, captured in a new exhibition at the Freud Museum in London.

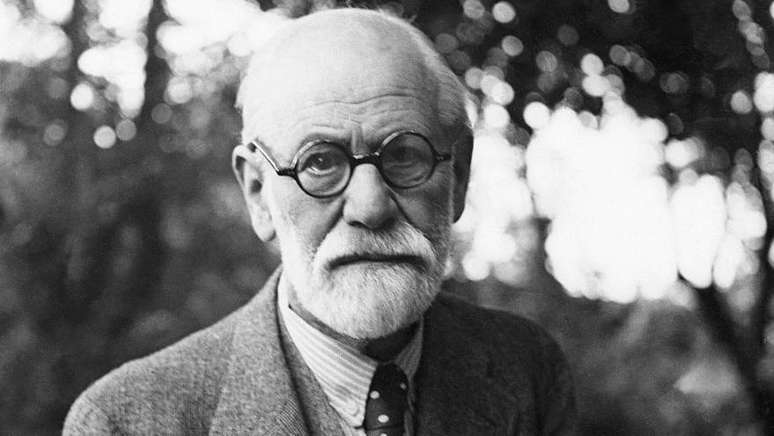

There are many facts known about the life and work of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939).

There is the Freud of books. The one who created the psychoanalytic method. The thinker of dreams, the unconscious, sexuality or the ego. The one who fled Vienna, Austria, under the Nazi threat. The avid cigar smoker.

Little is known, however, about international ties, particularly with regions as far away as Latin America.

But the truth is that one of the most important intellectuals of the 20th century had a particular connection with this corner of the planet, which was largely ignored by Europe at the time.

A new exhibition at the Freud Museum, located in north-east London where the father of psychoanalysis died in September 1939, speaks to this connection.

Through private letters, photographs, sculptures and books, the exhibition explores Freud’s enormous impact on Latin America, to the point that today the region is recognized as a major center of psychoanalysis.

Furthermore, the exhibition reveals the Austrian doctor and researcher’s fascination with the continent, who established close relationships with, among others, Brazilian, Peruvian and Chilean scientists.

“About Coke”

But how did Freud’s connection with Latin America begin?

According to researchers, the answer has to do with the use of coca.

As we know, around 1880, the researcher became interested in this drug – which was not illegal at the time – and discovered that digestion and mood improved after drinking water mixed with dissolved cocaine.

Freud’s findings in this regard were recorded in an 1884 article entitled Uber Coca-Cola (“About coca”, in free translation), where Latin America is mentioned for the first time in one of his writings, exploring the traditional use of the coca plant leaf in Peru and Bolivia.

“Freud’s relationship with Latin America began with research into the use of coca as a ritual medicine on the continent. It was his first intellectual contact [com a região]”, explains Mariano Ben Plotkin, specialist in the history of psychoanalysis and author of the book The esteemed Dr. Freud: a cultural history of psychoanalysis in Latin America (“Dear Doctor Freud: A Cultural History of Psychoanalysis in Latin America”, in free translation).

The historian adds that his mastery of Spanish was useful to him, a language he had learned as a child, self-taught, in order to read Don chisciotte, by Miguel de Cervantes, in the original.

“Freud did unique work on the anesthetic use of coca, which is very controversial today,” adds Plotkin.

Years after these studies, the doctor stopped defending the stimulant and analgesic benefits of coca, as reports emerged of the level of addiction and overdose deaths.

The Latin American ‘friends’

Even when he quit coke, he didn’t forget Latin America.

From Vienna, Freud continued to strengthen ties with leading doctors, psychiatrists and intellectuals on the continent.

Perhaps the most notable of these was Honorio Delgado, a Peruvian psychiatrist with whom he established a close relationship in the 1920s (and whom Freud described as his “first foreign friend”).

“Delgado came from Arequipa, from the Peruvian upper class. He conducted discoveries and experiments that were very current for the time, becoming one of the most important psychiatrists on the continent”, explains Mariano Ruperthuz, psychoanalyst and academic at the Andrés Bello University of Chile, in BBC News Mundo, the BBC’s Spanish-language service for Latin America.

Freud and Delgado exchanged letters, newspaper articles, and gifts for years. The Peruvian psychiatrist, together with his German wife, visited Freud several times in Vienna.

And although Delgado later rejected psychoanalysis, between 1920 and 1930 he was very active in expanding and spreading Freud’s ideas throughout Latin America.

So much so that he wrote the first Spanish biography of the Austrian doctor in Peru.

Freud also established relationships with illustrious Brazilian doctors, such as Durval Marcondes, who spoke German and translated some of the psychoanalyst’s research into Portuguese.

Marcondes was one of the founding members of the Brazilian Society of Psychoanalysis.

The scientist Gastão Pereira da Silva also corresponded with Freud and helped spread psychoanalysis in Brazil. He also hosted a radio program in Rio de Janeiro on dream analysis.

Other names also appear in the list of those who have had some type of relationship with the father of psychoanalysis, such as the Argentinians Jorge Thenon and Gregorio Bermann and the Chilean Fernando de Allende Navarro. Bermann went to visit him in Vienna, as did Honório Delgado.

Also on display in the London exhibition is a letter from Freud addressed to Juan Marín, a Chilean poet, novelist and diplomat, and to the Nobel Prize winner for literature Pablo Neruda, after the psychoanalyst was offered asylum in Santiago, following the Nazi persecution.

Although Freud never accepted such an invitation, for researchers this exchange of letters reflects, once again, Freud’s close connection with the continent.

‘Asymmetric’ relationship

Despite this, Mariano Ben Plotkin explains that these links between Freud and Latin American intellectuals were “quite asymmetrical” and “unequal”.

“Freud cared little about what they said about psychoanalysis. You can see it in the correspondence, where there are no theoretical discussions, but rather gratitude and a legitimate interest in that world”, he underlines.

“Freud accepted deviations from psychoanalysis in Latin America that would have been completely unacceptable in Europe. Because for Freud this region was a mission land, proof that psychoanalysis had reached distant and exotic places,” adds the historian.

This expansion of his theories across Latin America was extremely important for the Austrian doctor, the researchers say.

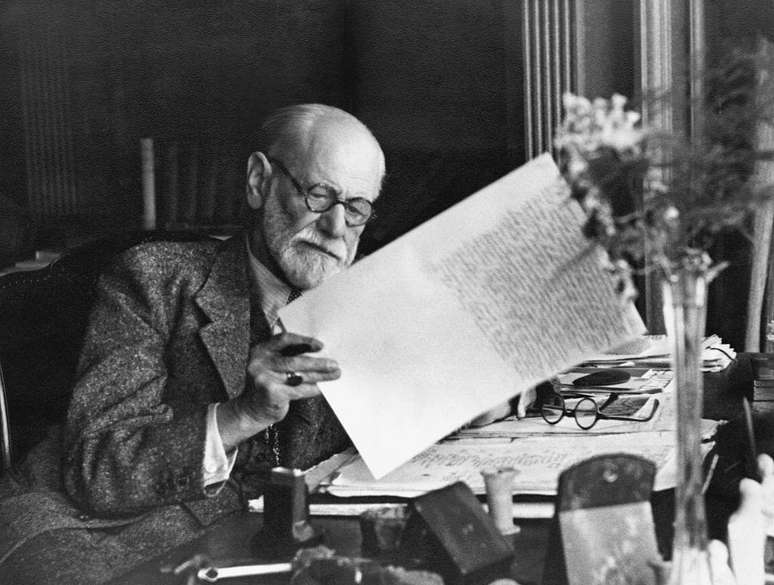

Proof of this was his strange interest in taking 34 of his 62 Latin American books – many of which had dedications – with him when he had to flee Vienna for London.

As a non-practicing Jew and founder of the psychoanalytic school in Austria, Freud was considered an enemy by Nazi Germany. His studies were publicly burned. The doctor’s entire family was the victim of intense persecution.

According to Mariano Ben Plotkin, of the 34 Latin American books that arrived in London, “Freud read none of them”.

“Half of them are written in Portuguese, and he didn’t read Portuguese. So you wonder: why did he bother bringing with him books that he had never read and would never read in his life? They had to show posterity that psychoanalysis had arrived in exotic countries”, says the expert.

Antiquities from Mexico and Peru

But Freud’s collection does not only include books from Latin America.

The psychoanalyst also preserved antiquities from Central and South America.

While it is unknown when or how he acquired these items, it is believed that these items may have been gifts or purchased in European antique shops.

A small terracotta statue of a kneeling man from Nayarit in western Mexico is on display in his London home.

Additionally, there is a Moche vase with a necklace from Peru that researchers believe was donated by Honório Delgado.

For Jamie Ruers, curator of the exhibition Freud and Latin Americathis was another of the things that fascinated the doctor from the continent.

“If we look at Freud’s antiquities, he was always fascinated by past civilizations. Most of the objects in his collection come from ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt… I think the idea of learning about incredible cultures and Ancient civilizations both always fascinated him,” he said.

“And Freud saw Latin America as an exotic place, no doubt,” he adds.

Freud’s influence in the region

All of the above perhaps explains why Freud’s ideas were so well received in Latin America, to the point that today cities like Buenos Aires are home to the largest number of psychoanalysts in the world.

“When you think of psychoanalysis, places like Vienna, Paris, London or New York come to mind. But new research (published with the London exhibition) challenges this, because there is another place in the world where it has actually been embraced : Latin America,” says Jamie Ruers.

This is reflected not only in the large number of doctors on the continent who followed in Freud’s footsteps – and published his studies – but also in the way these ideas permeated Latin American popular culture.

For example, in Buenos Aires in 1930, a special section called “Psychoanalysis will help you” was created in the women’s magazine Idilio, which analyzed and illustrated the dreams of readers.

The Italian psychologist Gino Germani was behind the project. Before the specialist’s death, Mariano Ben Plotkin spoke to him.

“I asked him why he thought he was doing that section on psychoanalysis. And he said, ‘Because he was selling it.’ Nothing else,” Plotkin says.

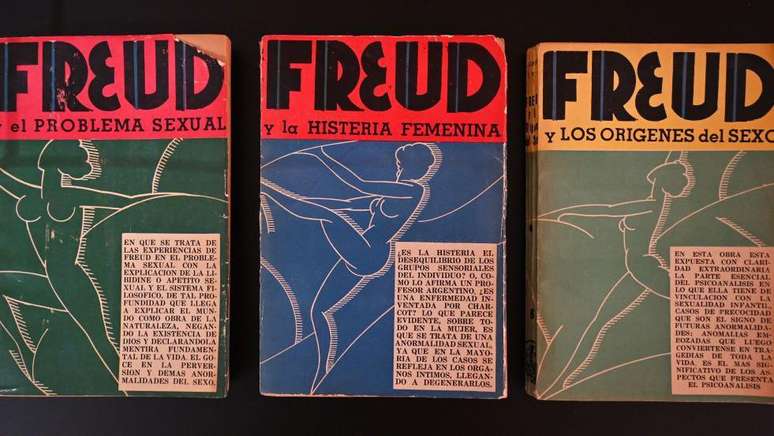

The same happened with a collection by the Peruvian poet and writer Alberto Hidalgo, through which he publicized Freud’s work.

“The collection was enormously successful, dealing with topics such as female hysteria or the origin of sex. It was published first in Argentina and then in other Latin American countries, and was even translated into Portuguese,” says Plotkin.

For the historian, psychoanalysis attracted Latin Americans so much because it allowed them to see “that there was the possibility of understanding the world from another point of view”.

This “other point of view” undoubtedly continues to impact many Latinos today.

And, 84 years after his death, Freud is present in a region that he never visited personally, but which is tormented by traumas and dreams like that method that the psychoanalyst created: listening to the former and interpreting the latter.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.