In 1879, one of the longest experiments in the history of science began. Members of the select group currently participating say it is exciting to be part of this initiative.

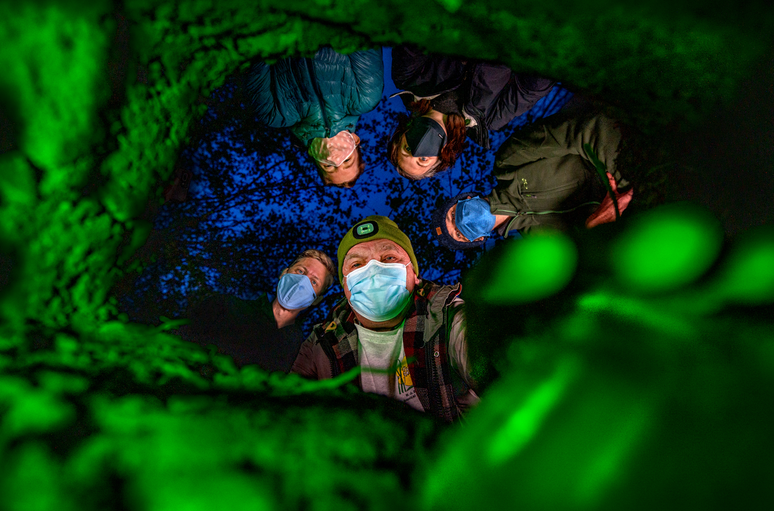

On a freezing April morning in 2021, American scientists took an old map, flashlights, a shovel and a measuring tape to search for a precious treasure buried 145 years ago.

In command of the small group was Professor Frank Telewski, biologist and leader of this small society of researchers at Michigan State University and custodian of the map inherited by several generations.

The area indicated on the map was identified and a hole began to be dug with a shovel. Scientist Marjorie Weber, the first woman to join the group, began digging carefully with her hands, to prevent a shovel blow from damaging the treasure.

He felt something hard under the ground, which made everyone cheer. But they soon discovered that it was the root of a tree. She continued a little longer, until she found something else: a stone. There was something wrong.

They checked the map and realized they had missed their initial calculations by about half a meter. Then they went back to digging again.

And there it was: a half-liter glass bottle filled with sand and seeds. Weber says it was like “bringing a baby into the world.”

The treasure was buried in 1879 and after 15 decades it was removed from the earth by this group of scientists engaged in one of the longest experiments in the history of biological sciences.

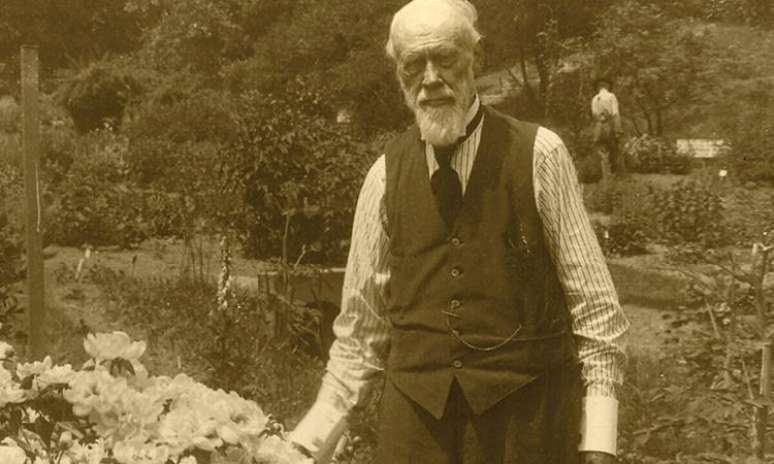

It was started in the past by botanist William J. Beal to determine how long a seed remains viable for germination.

The mission has been entrusted to several guardians, many of whom have not seen – and perhaps will not see – the end of it. Completion is scheduled for 2100. Although this too could be prolonged.

“Participating in Beal’s buried seed experiment was, without a doubt, one of the highlights of my career,” Professor Lars Brudvig, one of the scientists selected by the team, tells BBC News Mundo, the BBC’s Spanish-language service .

“To dig up and hold the bottle of 2021, last touched by Beal himself 141 years earlier, and then watch plant after plant sprout from those seeds… wow. It was a joy and an honor to be a part of this team.”

The grass

William J. Beal was a botanical scientist in the College of Agriculture at Michigan State University. He wanted to help local farmers increase agricultural production by eliminating weeds.

This type of grass seemed to grow out of control and at that time, in the late 19th century, farmers had to use hoes and spend a lot of time trying to keep it at bay.

Therefore, Beal wanted to understand their behavior and decided to investigate how long weed seeds could persist underground and be viable for germination.

To find an answer, he decided to fill 20 glass bottles with 50 seeds from 23 weed species. She buried them face down, to prevent water from entering, on the grounds of Michigan State University. And so as not to forget the exact location, he made a map.

The initial plan was to take out a bottle every five years to see if the seeds still worked.

He was responsible for monitoring the experiment in the first decades, a period in which some seeds continued to germinate.

At the age of 77 he retired and left the experiment in the hands of his colleague Henry T. Darlington, a 31-year-old botany professor who had many years ahead of him.

Beal’s ‘Spartans’

Since seed viability was maintained in the first five years, in 1920 the period increased to 10 years. And as they continued to sprout, in 1980 the wait was extended to 20 years.

Over the decades, the experiment has had seven guardians. The “Spartans”, as they call themselves, want these bottles to remain stored in a place away from curious people.

“It’s not signposted or patrolled, but it’s pretty safe and no one would stumble upon it by accident. If you drove past, the place would look like any other part of our 2,000-plus-acre campus,” Brudvig says.

“We used a map to triangulate the location based on key landmarks.”

Since 2016, the leader of the experiment is Frank Telewski, whom he appointed as custodian of a copy of the map in case something happened to it.

In 2021, they unearthed bottle number 14 of the 20 that Beal had placed underground.

The sleeping beauties

After nearly 150 years, some seeds continue to germinate, which has given scientists more information about their dormancy or longevity.

Unlike decades ago, experts are now able to conduct studies that they could not have imagined in Beal’s time, such as DNA research.

A recent molecular genetic test confirmed the presence of a hybrid Verbascum blattaria AND Verbascum thapsusor mullein, which was accidentally included among the seeds of pot number 14.

Apparently, Verbascum They are the most dormant plants, as others have lost the ability to germinate in the first 60 years.

Although Beal’s initial goal was to help farmers eliminate weeds by determining seed longevity, after 144 years there is still no answer.

Brudvig says the seeds they have are like Princess Aurora from “Sleeping Beauty.”

“Latent seeds are alive, but they ‘sleep’ and wait for the right stimulus before waking up (germinating). But while Princess Aurora awaits the kiss of her true love, the seeds in the soil seed bank await stimuli such as the light of sun, adequate temperature or adequate humidity conditions that will make them germinate and start growing,” he explains.

“A key issue is that seeds of different plant species can survive in a dormant state for different periods of time,” continues Brudvig.

“At some point it is too late, even when the right stimulus is given. For the plant species tested in Beal’s seed experiment, we learned that this time period ranges from 5 to 140 years.”

Do weeds never die?

The group pays close attention to seed management to achieve consistent results. They dig the seeds at night to prevent sunlight from affecting them in any way. And in laboratories they are able to generate conditions from the natural environment.

“We used a growth chamber with carefully controlled temperature, light, and humidity during plant germination for this experiment,” says Brudvig.

In addition to the questions originally posed by Beal, the experience remains relevant to answering additional questions that the botanist set out to resolve.

“The relevance of the experiment has also grown over time, in ways that I’m not sure Beal could have imagined nearly 150 years ago,” the scientist says.

For example, both rare native plant species and problematic invasive plants can remain dormant in the soil, sometimes for many years, increasing the potential benefits and challenges for managing native ecosystems.

Knowing more about this can help efforts to restore native ecosystems, such as grasslands and forests, from areas of ancient cultures.

“Our results help document which plant species, e.g Verbascumwhich might be problematic weeds for a restoration project like this, and which other species might not be, depending on how long a field was cultivated before being restored,” explains Brudvig.

It will still take several generations of Spartans to reach bottle number 20, which is expected to be unearthed in 2100. But scientists have not ruled out the possibility of extending the period between each excavation.

Will they germinate more than 220 years later? Weeds never die, as the saying goes?

These discoveries will be the responsibility of other generations.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.