In a year when around 50 elections will be held around the world, including Brazil, experts and governments are trying to prepare for the possible uses of artificial intelligence models in creating disinformation narratives.

Six fingers on the hands, face that doesn’t seem to belong to the body, eyes that don’t follow the movements, arm that moves strangely.

So far, these are common problems with synthetic images generated by artificial intelligence (AI).

The apparent flaws made it possible to spot the use of artificial intelligence at a glance. From now on, however, experts warn that human analysis alone will no longer be sufficient in this process.

“This window is closing,” warns Mike Speirs of Faculty AI, a London-based consultancy that develops models for detecting synthetic content (produced by or with the help of artificial intelligence).

“There is a constant refinement of models based on the almost adversarial nature between those who generate (content) and those who work to identify,” he adds.

In a year when around 50 elections will be held around the world, including Brazil, experts and governments are trying to prepare for the possible uses of artificial intelligence models in creating disinformation narratives in order to influence outcomes.

The challenge is great.

Models that generate content using AI learn from user-identified errors and detection methods.

Therefore, both human practitioners and mechanisms developed to detect the use of AI in a still or moving audio or image need to monitor improvements made by “adversary” synthetic content creation systems to understand new defects and therefore be able to find them.

As content generation and detection models evolve, flaws become less and less obvious, especially to the naked eye.

“The way we understand today that content is synthetic may not be valid tomorrow,” says Carlos Affonso Souza, director of the Rio de Janeiro Institute of Technology, adding, however, that the most popular applications still leave more than five fingers.

‘Arms race’

Oren Etzioni, professor emeritus at the University of Washington and researcher in the field of artificial intelligence, is emphatic: “It’s an arms race. And we’ve gotten to a point where it’s extremely difficult to make this assessment without using intelligence models artificially trained for this.”

However, access to tools for detecting synthetic or manipulated content is still quite limited. In general, it is in the hands of those who are capable of developing them, or governments.

“If you have no way of knowing what’s true, you’re not in a good place,” he adds.

ITS-Rio’s Souza says one of the challenges presented is to constantly train and update detection models not only to recognize manipulated or AI-produced content, but also to educate humans exposed to it.

“We are currently poorly equipped, both in terms of technology and methodology, to address this debate,” he says. “We will have to make use of digital education tools, constantly educating and updating society on the topic.”

Speirs agrees. “This is a broader social problem, in which technology plays an important role. Therefore, in addition to investing in detection, we also need to invest in media education.”

Etzioni says he is generally optimistic about artificial intelligence, but recognizes the scale of the problem, especially for the electoral process.

“Social media gave us the ability to easily share information. But the ability to generate content still belonged to people. With artificial intelligence all this has changed and the cost of producing content has dropped to zero. This year it will be critical for us to understand the potential of this in disinformation.”

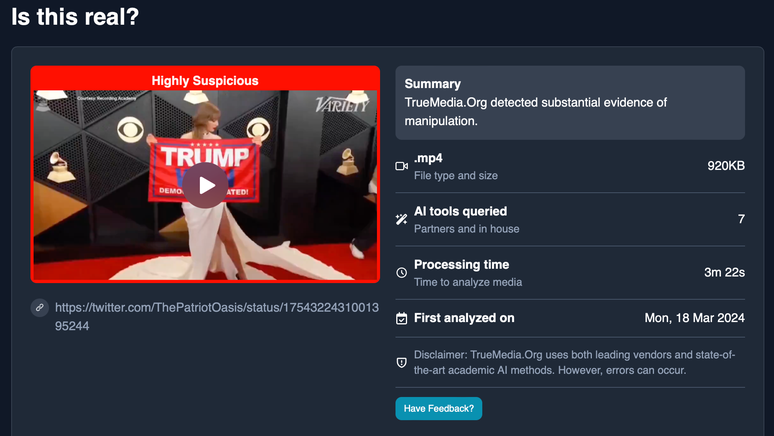

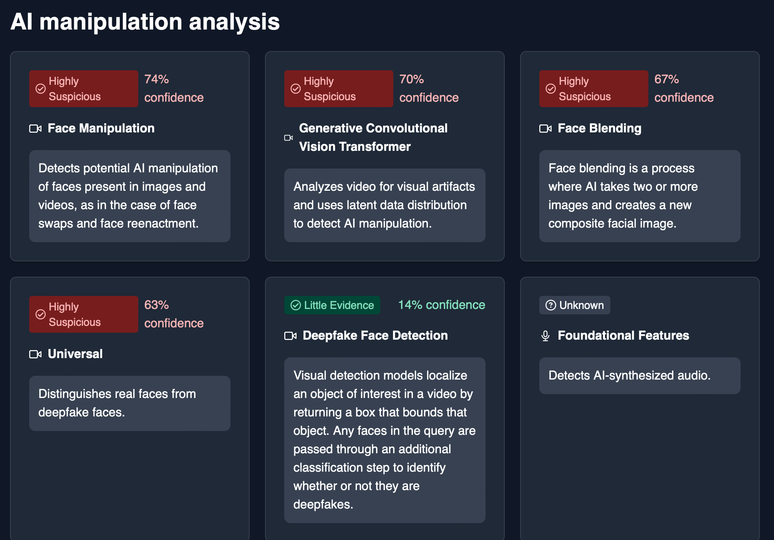

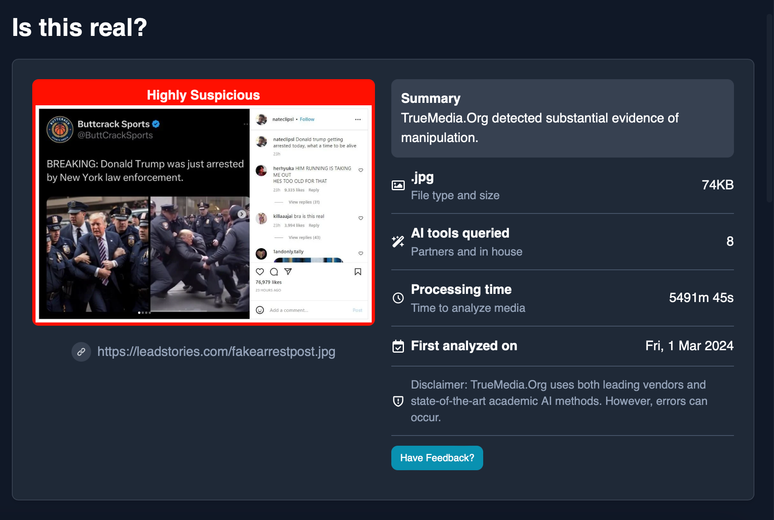

Fearing the impact on the information ecosystem, particularly with the use of deep fakes in the US presidential election, Etzioni created a non-profit detection tool, True Media, which is offered free to journalists.

The content is analyzed by the organization’s AI models within minutes, and the user receives an estimate of how likely the content is synthetic or manipulated.

“In a world where people can be easily manipulated, it is important that the press is part of the solution.”

Brazil and the limits of the TSE

In Brazil, there is no less fear about the impact that AI content generation will have on the electoral process.

In an effort to anticipate possible problems that may arise, such as the difficulty of quickly knowing whether content has been generated or manipulated by artificial intelligence and to prevent the spread of false narratives based on synthetic content, the Higher Electoral Court (TSE) has updated the rules of electoral propaganda in January, defining the possible uses of AI.

Content generated with artificial intelligence tools will be allowed as long as it is marked by campaigns, deep fakes are prohibited and platforms must “immediately” remove these – and other – content that violates the rules, under the risk of being held civilly or administratively liable, according to the rules.

Forbidding deep fakes and require the immediate removal of this type of content, the challenge of detection lies with the platforms.

For Francisco Brito Cruz, executive director of InternetLab, the new rules force technology companies to exercise greater supervision and moderation on the content circulating within them.

“Nowadays they have no legal incentive to ban deep fake in its terms of use and moderate this type of content without a court order. They do it because they want to, but they don’t have to. And they will only be held responsible if they fail to comply with an order. With the new resolution there will be those who will think they have to act, yes (before receiving a court order),” he warns.

Souza, of the ITS, views the measure with reservations.

“I understand that the TSE will, in a sense, entrust this first line of combat to the platforms. And, if they fail, they will be held accountable. In a sense, it is to think that the liability regime is, in itself, a sufficient incentive for companies to adopt means to identify synthetic content. It seems insufficient for this to develop,” he analyzes.

In the 2022 election, platforms had a two-hour deadline after receiving a court order to remove content or accounts.

The current text does not clarify whether active monitoring will need to be carried out to identify and immediately remove such content, or whether the immediate removal obligation only concerns accounts and content subject to court order, generating widespread discussion among digital law experts .

InternetLab’s freedom of expression and elections coordinator for the Internet Rights Coalition, Iná Jost, says that calling for the immediate removal of content without citing the need for a court order is at odds with the Marco Civil da Internet and the electoral law.

“We need more information. Actively removing content without very clear regulatory and legal parameters exposes free speech to undue restrictions that can be very harmful to the debate of ideas,” he says.

And the risk of active monitoring, Souza warns, is a high number of false positives, that is, content removed as AI, when in reality it is not.

“All this will take on a political connotation. And there will be parties interested in the analysis of the content who will say that the removal was done to favor one candidate or another, and that the platform is partial.”

And he warns: “We can expect that any discussion about synthetic content, and the traps we are building for ourselves with this accountability system, will fuel narratives of misinformation largely supported by artificial intelligence.”

The report contacted the TSE, but did not receive a response until the close.

This Wednesday (29/5) the National Congress decided by a wide margin to maintain the veto imposed by then President Jair Bolsonaro on the national security law. Among the vetoed sections are the one that criminalized deceptive mass communication, the so-called fake news,

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.