The pages of medieval books are filled with an intriguing creature: the giant snail.

The knight draws his arm back and prepares to attack. He wears typical 14th century armor, with chain mail, belted tunic and helmet.

Standing on a small meadow, he holds a shield in his hand on which, inexplicably, his own face is depicted. With his other hand he brandishes a mace, which points to a religious text on the yellowed page of the medieval book on which it was drawn.

But even within the pages of ancient books, knights face mortal dangers.

This particular knight’s adversary is a particularly elusive beast, an enemy that is often found creeping along the edges of the pages, engaging noble adversaries in life-or-death combat.

These creatures sometimes appear to float as they attack knights in mid-air. And in some cases there is more than one.

This is the warrior snail, a unique phenomenon in medieval times. And why they were illustrated remains a complete mystery today.

“This has created great perplexity among art and literary historians, who wonder what exactly they mean,” says medieval literature professor Kenneth Clarke of the University of York in the United Kingdom.

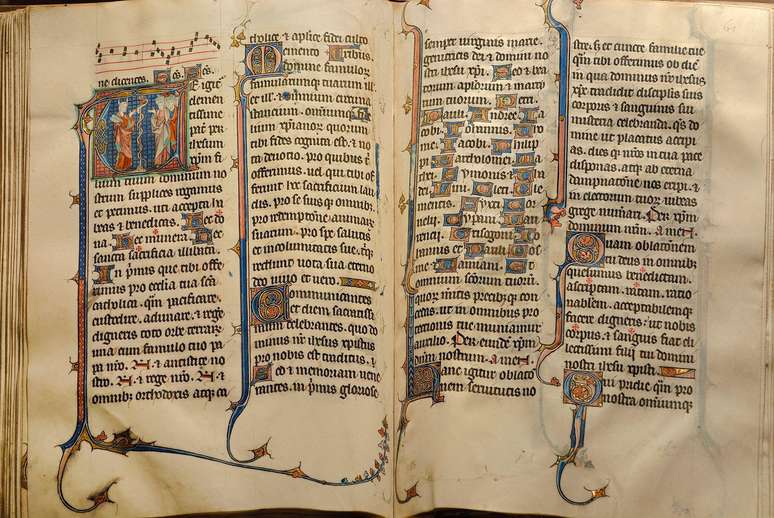

Artwork found in the margins of books is known as “marginalia”.

In the Middle Ages, when the text of a manuscript was complete, the most important parts could be elegantly finished, such as detailed borders of wavy foliage, fantastical creatures, and other miscellaneous designs.

Sometimes they were added immediately. In other cases, many decades later. But it was not a casual task. They were often painted with precious pigments such as lapis lazuli or highlighted in gold.

“They were very, very, very expensive books, with very few readers,” according to Clarke.

These decorations are found in a wide variety of religious works. They include psalters (with psalms), books of hours (with prayers), breviaries (with daily prayers), pontifical books (with rituals conducted by bishops), and decretals (papal letters).

The decorations could be bizarre, funny, grotesque and even crude. Bare buttocks, penises, medical conditions, and a surprisingly large number of bloodthirsty rabbits adorn the pages of what would otherwise be sober, devotional books.

Often the marginalia appear to have little relation to the text of the book. But for a brief period in the late 13th century, book decorators across Europe adopted a new obsession: warrior snails.

In a comprehensive study of these fighting gastropods, art historian Lilian Randall counted 70 examples, in 29 different books. Most of them were printed between 1290 and 1310.

These illustrations are found throughout Europe, particularly in France, where a prosperous manuscript production industry flourished at the time, according to Clarke.

The specific scenarios in which warrior snails appear vary. But overall, they followed the same shape as an aggressive snail, attacking a rider.

Often the mollusk’s antenna (technically, its upper tentacles, or omatophores) was pointed aggressively forward, as if it were a sword. One of these snails appears fighting a naked woman.

Some of them are illustrated not as ordinary molluscs, but as hybrids of snails and humans, obviously ridden by rabbits.

At some point, the warrior snail meme began to appear in other places in the medieval world, such as cathedrals. The molluscs were carved into their facades or, in one case, hidden behind some kind of folding seat.

But why are they there?

“The fight between the snail and the knight is an example of the world turned upside down, a broader phenomenon that produced many different medieval images,” says professor of medieval art Marian Bleeke, of the University of Chicago, US.

“The basic idea is the inversion of expected or existing hierarchies,” he explains. “The intention is to surprise and even be funny – I think we understand that implicitly today.”

But we still don’t know if these drawings had deeper symbolic meanings beyond changing the status quo.

“The knight had to be strong and courageous, capable of defeating all enemies,” says the master. “But here he’s hiding out of fear of a snail or even being overpowered by it. What we might not agree on is where we should go from this point.”

There are many interpretations for these illustrations, such as the idea that the battle against the snail symbolized class struggle, or even resurrection.

One leading hypothesis is that the knights depicted facing the snails represented cowardice and may have been included ironically alongside religious texts.

Randall points out that many slug scenes include a knight kneeling in prayer before his gooey adversary. In others, he is laying down his sword. And still others show a woman begging the valiant knight not to fight such a deadly enemy.

In developing the idea of the vile knight, Randall suggested that the snail might be a political commentary. In this case the knights would represent the Lombards, a Germanic people who inhabited the Lombard empire, in the territory where Italy is today, at the end of the 8th century.

“[Os lombardos eram exibidos] like this group that collected taxes but was also involved in usury,” explains Clarke.

In medieval France, where most of the snail drawings were found, the Lombards were vilified in various ways. They were said, for example, to be cowardly and unhygienic. Randall noted that in the 12th century they were synonymous with behavior contrary to chivalry in general.

A popular legend has it that a Lombard farmer had come across a heavily armed snail and that the gods encouraged him to fight it. But his wife begged him not to be so imprudent.

Clarke is skeptical of this specific idea, considering how common snail wars were in medieval books. And Bleeke explains that today’s historians generally don’t believe that images in the margins of books have such narrow meanings.

“I really don’t think images work that way,” he says. “I would like to observe how the snail was represented, what it looked like and where it was located, in order to analyze the meaning it represented in a specific case.”

Regardless of whether Randall was right or not, Bleeke believes the drawings can teach us something important about impressions of masculinity in the medieval world.

“The strong, courageous knight is an ideal, or an idealized version of masculinity. The fight against the snail undermines this notion,” he explains.

“For me, these images show us that gender has never been as stable or safe as some people like to think. It has always been contested.”

Read the original version of this report (in English) on the BBC Innovation website.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.