Patricia Wiltshire never imagined she would end up helping solve crimes, but the professional has been contributing to justice for decades.

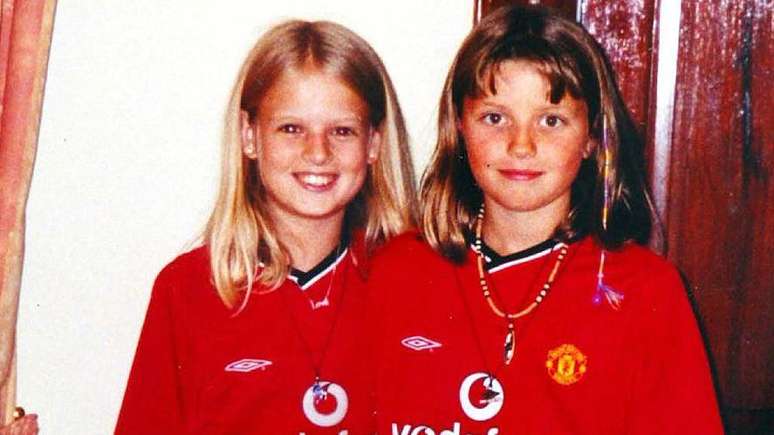

On a summer Sunday in 2002, Jessica Chapman went to a barbecue at her best friend Holly Wells’ house. They played all afternoon and, around 6 p.m., they went out to buy candy and never came back.

That day, August 4, one of the most extensive searches in British criminal history was carried out, with the help of volunteers from Soham, Cambridgeshire, where the girls were from, and even US Air Force personnel stationed at nearby bases.

Police explored every possible lead and used the media effectively, ensuring the disappearance of the two 10-year-old girls was widely publicised, with calls from parents asking for their return and details of rewards for information.

However, nearly two weeks after Jessica and Holly went missing, hope has been dashed.

A ranger, who days earlier had noticed an “unusual and unpleasant odor” in a forest, returned on Aug. 17 to investigate the source of the smell.

He found two bodies in an irrigation ditch surrounded by weeds.

Although in a state of decomposition and with signs of an attempt to burn them, a DNA test confirmed, a week later, what was feared.

It was difficult to establish the cause of death, but it was known that they had not been killed there, but had been transported dead and abandoned 30 kilometers from their homes.

But when, how and who?

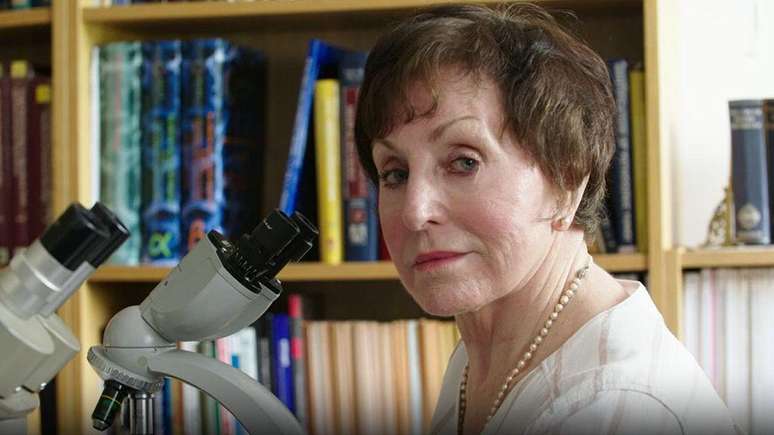

“The Welsh Witch”

In the time between the girls’ disappearance and the discovery of their bodies, the investigation team assembled a panel of experts, including forensic ecologist, botanist and palynologist Patricia Wiltshire.

By that time, she was already a well-known consultant because her findings helped bring justice to several cases.

“Sometimes the police call me ‘the Welsh witch’ because of the way I process a lot of data and come up with ideas,” she says. “But it’s not magic, it’s analysis.”

The scientist says she never imagined that her professional path would lead her to this specialization.

Born and raised in a small town in South Wales, she left home at 17 and went to London.

She worked for many years, first as an assistant in a doctor’s office and then as a secretary in a company, a profession that her first husband considered more appropriate for a woman.

Since she always loved nature, she enrolled in evening classes in botany and her teacher encouraged her to enroll in university.

He says he had never thought about it, but he went to have an interview with the principal of King’s College London and, “after a long conversation, in which I did most of the talking, he said to me: ‘I’ll see you in October’.”

“I learned as much as I could about amazing things. I went to other departments and did advanced studies in biogeography, geology, and parasitology of all kinds.”

After graduating, he continued to teach at the same university for 15 years, until accepting a new job at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London.

“The interesting thing is that I got this job because of my love of all things microscopic,” she says. “You don’t realize what really fascinates you until you try it all, and I loved the little things.”

Thus began his career as a palynologist.

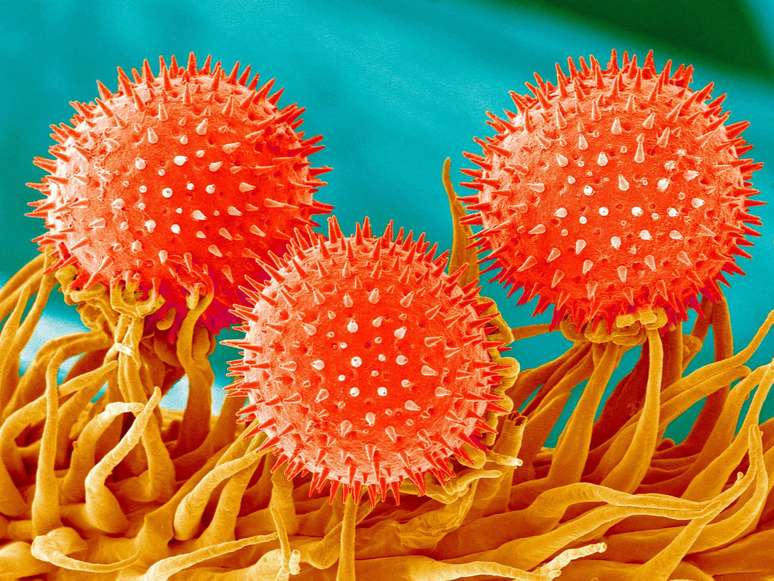

Palynology is the scientific discipline that deals with the study of plant pollen, spores, and some microscopic planktonic organisms, both in living and fossil form.

“I devoted myself to environmental reconstruction, in places like Pompeii and Hadrian’s Wall.”

Studying this area reveals what the landscape was like in ancient times because pollen and spores “can survive for millions of years.”

However, studying pollen to find out whether fields were once agricultural or wild and what grew in them is far from solving crimes.

What motivated the change of direction?

“A call.”

In 1994, when Wiltshire was 50, he received the phone call that changed the course of his career.

She was a Hertfordshire police officer who asked her if she could help investigate a murder case.

A charred body had been dumped in a ditch, and tire tracks were found in a nearby area. Police needed to know if the suspects’ car was at the crime scene.

“I’ve never done anything like this before, but I scanned everything in (the suspects’) car and found that the pollen on the pedals and wheel area matched pollen on the edge of a farm field.”

“When the police took me to the crime scene, I asked them not to tell me where they found the body, because I wanted to test my study.”

“It was a very large place, but after walking around I was able to pinpoint the exact location based on the type of flowers that were in that area,” he says. “It was a moment eureka for me because I didn’t think it would be that specific.”

Despite his initial skepticism about forensic ecology, he began working on an increasing number of cases and climbing “a very steep mountain of learning.”

“If I hadn’t had all the experience I had in hospital laboratories doing palynology, bacteriology, all that weird and wonderful stuff, all that ecological field work, I wouldn’t be able to do what I do now.”

On its side was pollen which, unlike other tests, is not easily removed as it incorporates into everything that touches it.

“It’s all around us and you inevitably come into contact with it,” he says. “Every contact leaves a trace,” the palynologist observes, quoting Edmond Locard, the pioneer of forensic science known as the “Sherlock Holmes of France.”

And use these traces to establish who went where.

“Actually, there’s more: by mapping clothing, I can tell which body part did what,” he says. “In one specific attempted murder case, for example, a man tried to strangle a girl under a streetlight and said she wasn’t there.”

“Because I took detailed samples from the crime scene, I was able to reconstruct what he was doing at that moment. After examining his clothing, I proved that he had not only been there, but had also tripped over the fence with his left shoulder, dragged the girl through a fence, knelt down, and so on.”

From his first case in Hertfordshire, Wiltshire was able to use the wide range of subjects he studied to develop forensic ecology, which has helped solve many cases over the years.

Some with huge repercussions in the UK, such as the murders of Sarah Payne, aged eight, in 2000, and Milly Dowler, aged 13, in 2002, as well as the murders of five women by a serial killer in Ipswich in 2006.

And what happened to Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman, whose bodies were found in a ditch?

The answer in the nettles

The police asked her to go to the crime scene.

“When I go to a crime scene, everything is important: the terrain, the vegetation, the amount of light, the insects. Everything forms an image from which you can get a lot of information for the police,” he told the BBC.

In this case, he said, they wanted to know how the killer ended up in the ditch, because they couldn’t find a way out.

“The nettles were chest-high. I walked carefully and found them. The vegetation that had been trampled, I could see what happened. But of course that’s not enough: you have to prove it.”

For Wiltshire, trampled nettles found at the crime scene were key to calculating when the bodies were left there. So he designed a groundbreaking experiment.

“The nettles were trampled, but they recovered, so the important thing was their growth. When you trample a plant, you interrupt the flow of hormones from the tip to the rest of the plant. What you see is not only the interruption, but also a chronology.”

“We set up on a local farm where there were beds of nettles, and the director came in twice with a big weight on his back.”

“Those nettles were photographed every day and we watched them recover. They behaved exactly like the nettles at the crime scene.”

“After about 12 and a half days we reached the same number of nodes and the same distance between the nodes.”

The Wiltshire experience revealed that the girls’ bodies were placed in the ditch shortly after they disappeared.

“I showed the police where the attacker entered the ditch, and when I went in, I found Jessica’s hair on a branch,” he says. “The approach route is important because there could be clues and you can look for fingerprints along that route.”

Meanwhile, police investigations have identified the prime suspect, Ian Huntley, the caretaker of the girls’ school where the girls studied.

Overwhelming evidence

During the investigation, Huntley positioned himself as something of a spokesperson for the town of Soham, and was frequently interviewed by the press.

He constantly asked the police for information, not only about the investigation, but about other details that aroused the investigators’ suspicions.

During a forensic investigation at their home, fibers were found from the shirts Jessica and Holly were wearing. But he had an explanation: that day the girls had left because one of them was bleeding from her nose, and he helped them, which was plausible.

Investigators continued to search for further evidence.

They searched the school where Huntley worked and found items of clothing – burned and cut – that the girls were wearing when they were last seen.

When Wiltshire analyzed the clothes, he found that “all they contained were fragments of vegetation, chiefly the fruit of the alders which hung thickly over that ditch.”

“I realized right away that the girls were dressed when they were thrown into the ditch.”

This was all part of the incriminating evidence against Huntley.

Wilstshire was one of the experts who gave evidence at the trial which sentenced Ian Huntley to life imprisonment with a minimum of 40 years.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.