166 years ago, on October 31, 1858, children and adults began dying mysteriously in Bradford, England, sparking panic in the country.

Giving a handful of candy is as synonymous with Halloween as a spooky costume or a ghoulish pumpkin.

But 166 years ago, on October 31, 1858, this normally harmless tradition caused the deaths of several children, caused panic in Bradford, England, shook the country and led to changes in the laws of the United Kingdom.

All because someone wanted to save on the use of sugar in the production of pharmacy sweets.

When William Hardacre finished the day’s work, he congratulated himself on his sales success.

That day, the owner of the local market stall, known to many as Humbug Billy, had not only sold five kilos of mints to Bradford residents, but had also bought them cheaply.

Picking up the candy from the retailer, he noticed that it was darker than usual. He bargained with the confectioner Joseph Neal and managed to save half a penny per pound.

But Hardacre’s failure to question the quality of the product was a grave mistake: by nightfall the next day, many of his customers were dead.

Initially, the doctor who treated nine-year-old Elijah Wright in the early hours of Halloween 1858 thought the boy had died of cholera.

The doctor, John Roberts, thought the symptoms – vomiting and convulsions – were consistent with the disease, then common in England.

An hour later, Joseph Scott’s father left the house to find a doctor for his 14-year-old son, who had suddenly become seriously ill. By the time Scott returned, it was too late.

Both boys, it later turned out, had bought candy from Humbug Billy the day before, but the connection had not yet been made.

It was Dr. John Henry Bell who suspected sweets when he visited two boys in the mid-afternoon.

Bells around the city

Five-year-old Orlando Burran and his three-year-old brother John Henry lay dead before him; the father and two other people from the same house were also ill that morning and had all eaten the mints.

The doctor then took some sweets to be analyzed by the chemist Felix Marsh Rimmington.

As the day progressed, reports began to come in from across the district of people falling ill and dying.

Alerted by the sweet suspects, the police went to the home of Hardacre, the market seller, and discovered that he was also ill, in bed, and that he had sold around 1,000 sweets the day before.

“The police were horrified to discover that she had been there [tantos] sweets out there,” says Lauren Padgett, a doctor and assistant curator of collections at Bradford Museums and Galleries.

“At that time, it was late Sunday night, and they went out into the streets ringing bells to get people’s attention, shouting warnings. They went from bar to bar telling people, ‘Don’t eat the sweets, they’re poisonous.'”

Notices were quickly printed and posted in public places.

A list of those dead or seriously ill was published in the Bradford Observer newspaper and on 4 November the death toll reached 18, of which the youngest was just 17 months old.

The newspaper describes the growing list of victims as “the most terrible tragedy that perhaps ever hit the district… [espalhando] suffering, mourning and anguish”.

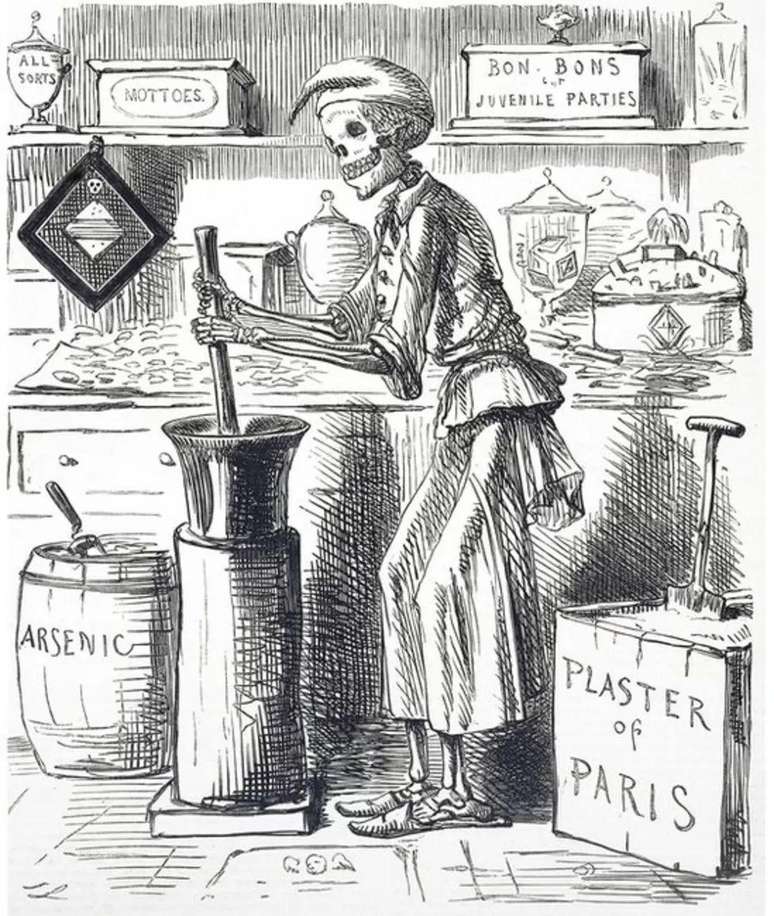

Investigators were quick to understand how the candy was tampered with.

They followed Hardacre’s trail to the confectioner, Joseph Neal, who thought he had replaced some of the expensive sugar in the sweets with chalk powder.

In the 19th century it was common practice to use the powder in place of expensive ingredients, as it could be purchased cheaply in pharmacies.

What Neal didn’t know was that on the day he sent his colleague for chalk powder, the apothecary Charles Hodgson was ill and told his inexperienced apprentice, William Goddard, where to find the product.

Unfortunately, in the same place there were two barrels of unmarked white powder: one containing harmless powder and the other containing poisonous arsenic.

“Goddard went to a barrel he believed contained chalk and collected 5.4kg, gave it to the young man who took it back to the sweet shop, where another employee began mixing them to make lozenges,” Dr Padgett says.

“This employee became seriously ill from exposure to arsenic, but instead of raising the alarm, he continued to produce them.”

When Humbug Billy went to get the goods, he got the discount due to the strange appearance of the sweets, which were then sold at his market stall.

When chemist Felix Rimmington analyzed the candy, he stated during the investigation that he found “arsenic in abundance, enough to kill.”

In just one tablet, he found 16 grains of arsenic, four times the amount considered a poisonous dose and enough to kill someone multiple times.

“It was an insane amount of arsenic,” adds candy and confectionery historian Alex Hutchinson.

“To us 21st century consumers, it seems crazy that this incredibly poisonous, odorless and tasteless item could be stored in an unmarked barrel along with other unlabeled material and could simply be handed over to someone on the other side of the world. counter, ” he says.

‘Disastrous for everyone’

Newspapers across the country covered the case, which caused a wave of protests.

The artist John Leech was perhaps as well known for his drawing of a skeleton mixing sugar in a sweet shop published in Punch magazine as he was for illustrating the first edition of A Christmas Carolby Charles Dickens.

Officially 20 people, including many children, died and another 200 became seriously ill, but Padgett suspects the numbers were much higher.

“It was very distressing for everyone,” he says. “Bradford was very small and close, so when something happened in the community, everyone was affected, and that’s what happened in this case. Chances are, people knew someone who was affected.”

The poisonings in Bradford, which had a population of around 50,000, highlighted the importance of ensuring the safety of medicines and consumer products.

The case provided impetus for the creation of the Pharmacy Act of 1868, which not only restricted the sale of toxic products and dangerous medicines to qualified pharmacists, but also established a regulatory framework for the sale of poisonous compounds that to this day requires the substances to be properly labeled.

Had it been in place ten years earlier, the law might have prevented Goddard from choosing the wrong barrel and selling the poisonous powder. But it wouldn’t have solved the larger problem of adulterated foods: the industry needed regulation and reform, says historian Alex Hutchinson.

“Until the 1820s, most of us lived in villages or small towns where we knew the people who provided our food. But with the Industrial Revolution, manufacturers began producing goods in large quantities and adding substances to dilute foods and preserve their shelf life, improve their appearance or make them cheaper and that was the issue in Bradford.”

A law preventing undeclared adulteration of products was finally passed in 1875 in the form of the Food and Drug Sale Act.

But the warnings could have been heeded much earlier, Hutchinson says. In 1820 the chemist Friedrich Accum wrote in his book Death in the pot (Death in the pan) that everyday foods such as milk, flour, beer and sweets were routinely adulterated.

“Accum’s book was a huge bestseller: he warned consumers to be aware of adulterating elements [em seus alimentos]”she says.

“But there was simply no legislation to protect people, and I think Bradford was the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Although laws have been put in place to prevent a tragedy like the one in Bradford from happening again, it is perhaps shocking to learn that no one has been convicted.

Trickster Billy was never arrested, but he lost the use of his legs and arms due to the bullets he ate. Neal, Goddard and Hodgson were arrested for manslaughter, but the inquest concluded that “arsenic was sold and mixed accidentally under the assumption that it was chalk dust”.

The grand jury dismissed the charges against Neal and Goddard, and, according to the Bradford Observer, the same judge halted the proceedings against Hodgson.

“No other outcome was expected,” the court report said. “The only truly criminal aspect of the episode was what the law could not achieve: the practice of adulteration and the supply of powders for that purpose. If the tragic episode teaches this lesson, it will not have been in vain.”

Ultimately, the chain of events that led to the Bradford poisonings was “pure incompetence,” Hutchinson adds. “But as a Halloween story, it’s pretty creepy.”

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.