Mark Jenkin is a cinematic force. The Cornish writer-director has cultivated a unique style of hand-crafted, experimental short films since 2002, culminating in the 2019 BAFTA-winning feature film. Bait: A fantastic black and white drama about the tensions of gentrification in a Cornish fishing village. Playing with cinematic grammar while remaining firmly in his West Country backyard, Jenkin managed to create something that felt both out of the past and thrilling, a trick he’s now repeated with his latest film.

Men (pronounced “Ennis Main,” meaning “Stone Island” in Cornish) is a startling and haunting second feature that consolidates his signature style, while expanding into new territory. BaitIts black-and-white aesthetic evoked early silent films, but had a modern setting (the Airbnb flooding Cornwall was the source of many complaints); Menmeanwhile, it’s set half a century ago, but sees Jenkin transitioning to color photography, albeit still shot on 16mm, and still carefully crafted using traditional artisanal methods.

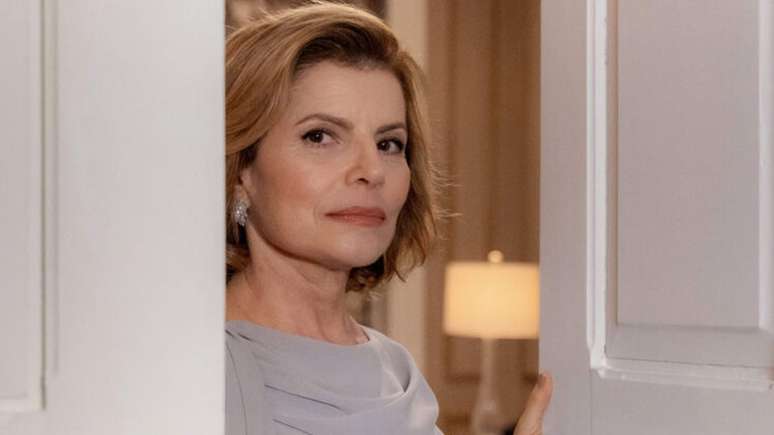

The departure from black and white is truly amazing, the quality, grain and finish make some of the colors really stand out, especially the bright red raincoat of the film’s main character, the unnamed “volunteer” (Mary Woodvine) . . It’s a visual motif that (albeit nonchalantly according to Jenkin) has echoes of Nicolas Roeg. Don’t look nowanother psychological horror about pain and loneliness, released in the year this film is set.

The experimentation that is Jenkin’s trademark is combined with new narrative experimentation.

This looks specific to 1973, but then, how Bait The lo-fi approach also gives it a timeless feel, as if the whole film is just a lost reel of found footage, washed up on the Cornish coast. The pace is calm and deliberate: we watch the volunteer carry out a carefully maintained ritual, leaving his ramshackle hut on a small island each morning, to check the progress of a cluster of presumably rare wildflowers, measure the soil temperature, and record the their discoveries in a logbook written in pencil. (His daily update, “No change,” sounds like that movie’s answer to “All work, no play…”)

Of course, any interruption of this endlessly repeating ritual leaves a strange feeling of unease. (Perhaps most disturbing is when tea supplies run out – it’s British horror, after all.) Jenkin’s trademark experimentation – eerie static close-ups of still faces, disorienting editing – is combined with a new narrative experimentation. , when the metaphysical reality of the Volunteer becomes blurred and visions of milkmaids, singing schoolchildren and even the Volunteer himself begin to appear inexplicably.

There are hints of the collective grief that accompanies a coastal community losing souls to the sea and a pagan connection between flowers and the Volunteer, ghosts of the past bubbling through the roots. But the logical explanations are only slightly implied. In the proud traditions of English popular horror, Men it can be a difficult experience; leaving you with the feeling of something old, but also, in Jenkin’s ambitious storytelling, completely new.

Source: EmpireOnline

Camila Luna is a writer at Gossipify, where she covers the latest movies and television series. With a passion for all things entertainment, Camila brings her unique perspective to her writing and offers readers an inside look at the industry. Camila is a graduate from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) with a degree in English and is also a avid movie watcher.