At the beginning of his career, Elvis solved an industry sales obstacle – but with his sudden success, came the reaction of a conservative society, horrified by the swaying hips of the King of Rock.

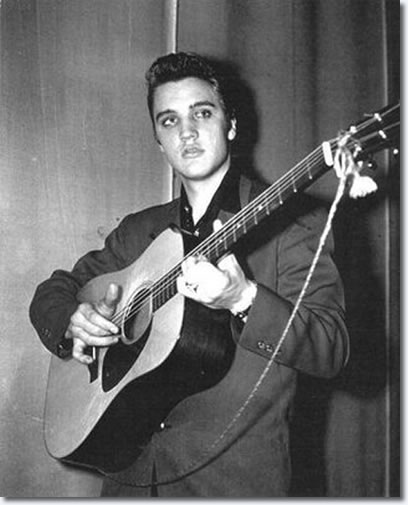

When 1956 began, the young Elvis Presley was at a marketing crossroads. RCA label executives scratched their heads: “What exactly to do with it?” Elvis had mixed the black sound with country music in Sun Records and became known in Louisiana Hayride, which was a country radio show. The so-called “rock culture” did not yet exist. Clear, Bill Halley & His Comets had blown up with “Rock Around the Clock,” putting ferment in the impending revolution. black artists like Chuck Berry (“Maybeleine”) and Little Richard (“Tutti Frutti”) were on the pop charts. There was no figure to connect the dots. Nobody knew it would be Elvis.

The bet

Steve Sholes, the man who bet on Elvis, was in a peculiar situation. He’d seen the singer perform several times at the Hayride and in country caravans, and instinctively sensed that Elvis had something more. The country music crowd was predominantly male, middle-aged, and conservative, but at Elvis’ concerts, it was mostly hysterical teenagers, wanting to get a piece of the singer. It was these people who should be the target. Sholes put pressure on RCA’s Marketing department to simultaneously promote Elvis as a country and pop artist. The executive aimed to achieve the same impact as Bill Halley, who started out in obscure western swing bands and was currently the country’s No. 1 artist.

For Elvis, oblivious to the machinations that took place in the offices of his new record company, 1956, until then, was pure routine. He spent the first few days of January in Memphis and hit the road with Johnny Cash. Then he did a few more shows with the Lousiana Hayride crew. The singer was so exhausted from these days on the road that when he returned to Memphis on January 8th to celebrate his 21st birthday, he didn’t party: he slept all day. On the 10th, he was in Nashville for the first recording session for RCA. He recorded, among others, “Heartbreak Hotel”, which was not well received by producer Chet Atkins and label executives. Even so, it was chosen by Sholes as their debut single. The launch was scheduled for the 27th of that month. The young man went on the road on his grueling tours, and the audience’s excitement was increasing. Wisely, Colonel Parker, invested in television. The singer was hired to appear on the TV Stage Show, run by brothers Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, veterans of the big band era. His first appearance on the show, which was broadcast from New York, was on January 28. On a rainy night, he sang the “Shake Rattle and Roll”/”Flip Flop Fly” and “I Got a Woman” medley. Elvis performed five more times in the following months, performing “Blue Suede Shoes”, “Baby Let’s Play House”, “Tutti Frutti”, “Money Honey” and others, but giving a special boost to “Heartbreak Hotel”.

All the promotion done by RCA and Elvis’ efforts paid off. By the end of March, “Heartbreak Hotel” had sold over 1 million copies and was No. 1 on the pop, country and R&B charts. Steve Sholes was finally able to laugh. He had heard that he had signed the wrong singer from Sun Records. After all, Carl Perkins had blown up the Memphis label with “Blue Suede Shoes,” which was soon recorded by Elvis as well.

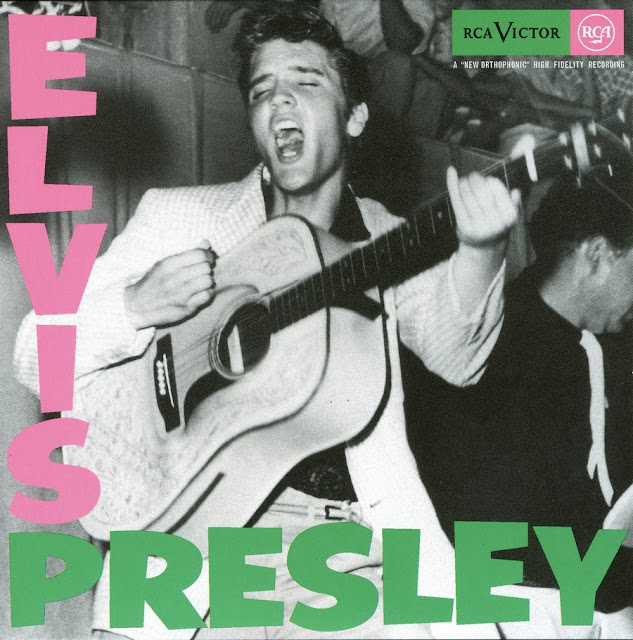

the first album

the first album by Elvis Presley, which had only the singer’s name, was also released in March. It was another trump card for Sholes. Teenagers didn’t have the money to buy them, but Elvis already had enough money to take a chance on the 12-inch format. In a short time, the record was already at the top of the charts.

With royalties from “Heartbreak Hotel”, the singer bought a house on Audubon Drive, located in a middle-class suburb of Memphis, at number 1034. Gladys and Vernon, his parents, liked the room, spacious and simple, where they could receive relatives. Soon the calm was disturbed by fans who started camping near the venue, hoping to find the idol. At first, he attended to everyone, but gradually his routine became disturbed. Elvis also spent more time on the road and was unable to fully appreciate his new residence.

tour and TV

On April 13, Elvis debuted in Las Vegas. The Colonel had secured a two-week stint at the New Frontier Hotel, along with comedian Shecky Greene and Freddie Martin’s orchestra. It wasn’t exactly a huge success. The city’s public, made up of wealthy adults, was not interested in the “atomic singer”, as had been promoted by the Colonel. The onlookers who went to the concerts only applauded politely, and the chaos and screaming present in the normal concerts passed far from the hotel’s stage. Critic Bill Willard wrote: “To teenagers, Elvis is a wizard, but to Vegas spendthrifts, he’s just a bore. Its trio of instrumentalists makes a raw sound, which has everything to do with the meaningless lyrics pronounced by the singer”. For Elvis, the days in Vegas served as a learning experience. He toured the other shows, watched his mother’s idol Liberace, and tried to soak up as much of the local showbusiness atmosphere as possible.

Afterwards, he was cast in Milton Berle’s show on the NBC TV network. It was a significant step. Berle was a television icon in the 1950s, and his show had one of the biggest audiences at the time. The transmission was made from San Diego, from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hancock. Elvis, dressed in dark clothes, rocked to the sound of “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Blue Suede Shoes”, and even participated in a humorous picture with Berle, in which he played his “brother”, Melvin. The singer found that a little appealing, but knew that his mother, Gladys, a fan of Berle, would like to see him perform alongside the veteran. Something symbolic happened backstage at the Milton Berle Show: in addition to Elvis Presley and his musicians, drummer Buddy Rich and his band were also on the show. DJ Fontana, Elvis’ drummer and Rich’s fan, came over to greet his drummer colleague. He was snubbed. Rich called Elvis and his musicians rednecks and was horrified when he realized that the future King’s troupe was playing without score and without rehearsing. When Elvis introduced “Blue Suede Shoes”, Rich sneered: “Gee, that’s a dread. Thank God it will pass.” Soon Rich’s jazz would become a museum piece. “I Want You, I Need You, I Love You” was the next single, but Elvis never had fond memories of the song. The flight on the way to Nashville for the shoot was bumpy and the small plane ran out of gas, nearly crashing. Nervous, Elvis did not respond on the recording and even got the lyrics wrong. In the end, a satisfactory matrix was obtained. The record inevitably reached number one in May.

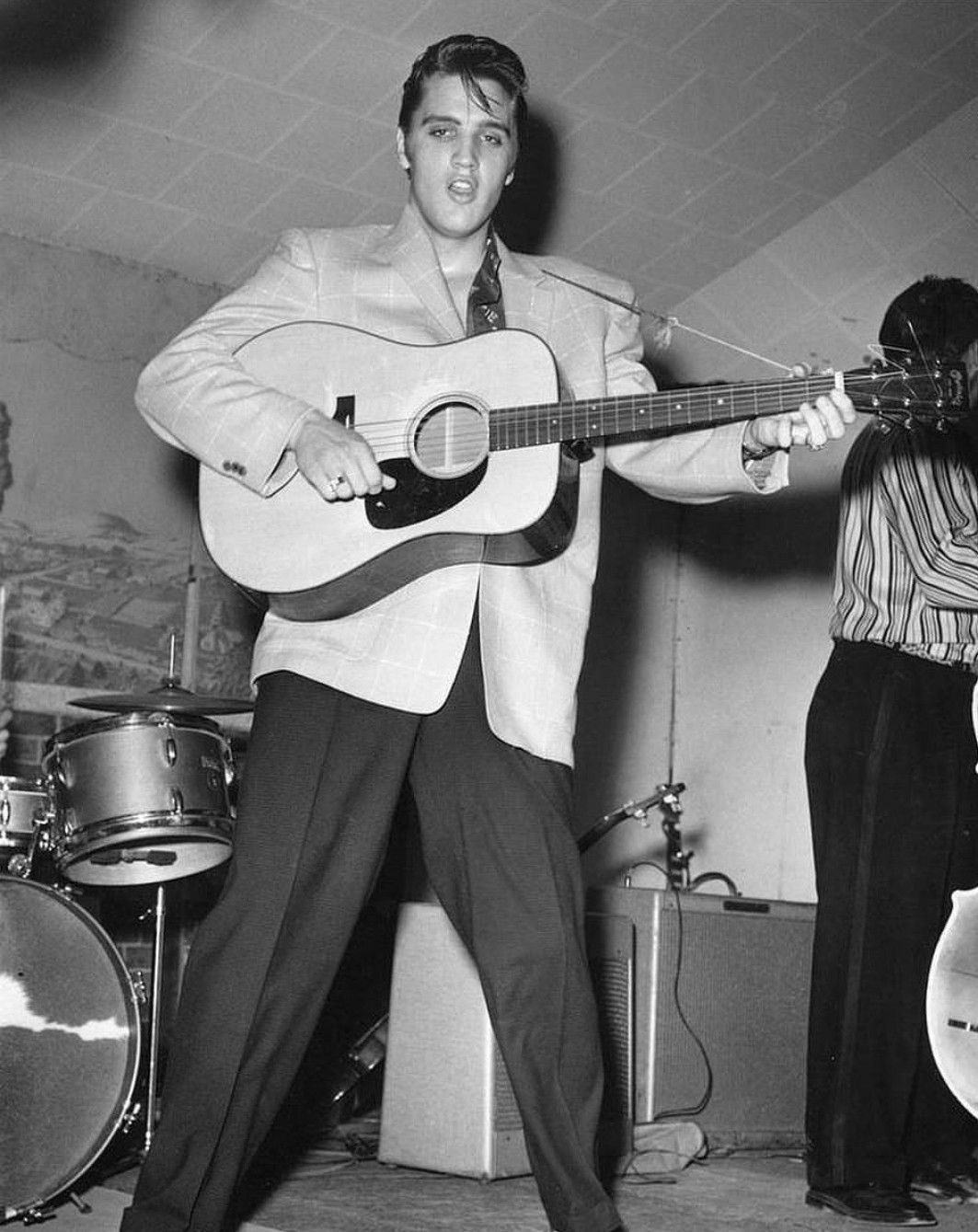

Elvis was already used to what happened in a television studio. For his second appearance on Milton Berle’s show, scheduled for June 5, he was much more relaxed. The playful presence of the presenter also helped. He went to promote “I Want You, I Need You, I Love You”, but he was entitled to one more musical number. On his ill-fated stint in Las Vegas, Elvis watched Freddie Bell and the Bellboys perform “Hound Dog,” a song by blueswoman Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton. The band’s interpretation of Bell was comical and the singer liked it, thinking it would go down well in live performances. On Berle’s show, he dispensed with the guitar. He swayed and danced like a stripper, twirling the microphone sensually but without apparent malice. He thought it would just be funny, but it wasn’t.

“Rock’s Guilt”

The next day, Elvis was finally getting national headlines and the attention of adults (and people who had never heard of him). Unfortunately, not in the way he expected. “Popular music has never gone as low as yesterday,” said Ben Gross of the New York Daily News. “On Milton Berle’s show, the singer swiveled his hips in such a vulgar and animalistic manner that his performances should have been confined to harbor docks and brothels, not national television.” The pompous The New York Times opined through the words of columnist Jack Gould. “Mr. Presley has no vocal ability whatsoever. The sight of young Presley babbling his unintelligible lyrics with his inadequate voice, complemented by his primitive movements, cannot be described in a family newspaper. It takes us back to the Stone Age.” Until then, the media had been shy about the new musical format christened by Alan Freed, rock, and now led by Elvis. Juvenile delinquency, the loosening of moral and cultural values, disorder in the streets, racial mixing and disinterest in religion: it was all now the fault of rock music and, by extension, its Hamelin Piper Elvis Presley. Southern American culture, always treated with indulgence and indifference, was now antagonized by the big-city media.

For Elvis, his relatives, friends and associates, the reaction to Berle’s concert was one of shock and awe. Before, Elvis was treated warmly. Now he was the public enemy, the poster boy for bad examples. In an interview with the Reuters news agency, he tried to defend himself. “I don’t try to be sexy, ma’am,” he told the reporter. “I just move with the music. I just swing my legs. It has nothing to do with any other part of my body.” Elvis resented the nickname Elvis The Pelvis (“that expression is the most childish thing coming from an adult”) and vented, “I don’t see how any kind of music can have a bad influence on people. I don’t understand how rock and roll can make someone rebel against their parents.” He also defended the style of music he sang. “People of color have been singing and playing like this for so long I don’t even know. They play like this in the tenements and listen to this music on the jukebox. Nobody gave a shit until I started singing that style. I learned from them. Back in Tupelo, Mississippi, I could hear old Arthur Crudup blasting. I thought that if I could convey that same feeling, my music would be like no one else’s.” Colonel Parker kept his cool and didn’t think damage control was necessary. The important thing was to let things cool down and everything to follow its course – many important agreements, already negotiated, could not be trivialized in polemics. Asked about the pupil’s movements, the manager said: “Next time, I’ll put a roll meter on the show”.

Source: Rollingstone

Camila Luna is a writer at Gossipify, where she covers the latest movies and television series. With a passion for all things entertainment, Camila brings her unique perspective to her writing and offers readers an inside look at the industry. Camila is a graduate from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) with a degree in English and is also a avid movie watcher.