Doctors and needles go together in modern medicine. According to medical literature, the history of the injection began between 1642 and 1650, when Christopher Wren, better known for being an architect than for his medical training, used a vein cutting technique (in which the vein is surgically exposed and a cannula is inserted inside under direct vision) to inject poppy sap into dogs through “needles” made of goose feathers.

The experiment was disastrous, as was the one carried out on humans by doctors Major and Esholttz in 1660, with fatal results due to the lack of knowledge of the adequate dosage and the need to sterilize the utensils. Documentation of the disastrous consequences of these experiments delayed the use of injections by approximately 200 years.

In 1776, Kohler in Germany cleared an infection in a patient’s esophagus through an intravenous infusion of tartar emetic, inducing vomiting which helped cure the problem. This crucial experiment allowed medicine to give injections a new chance.

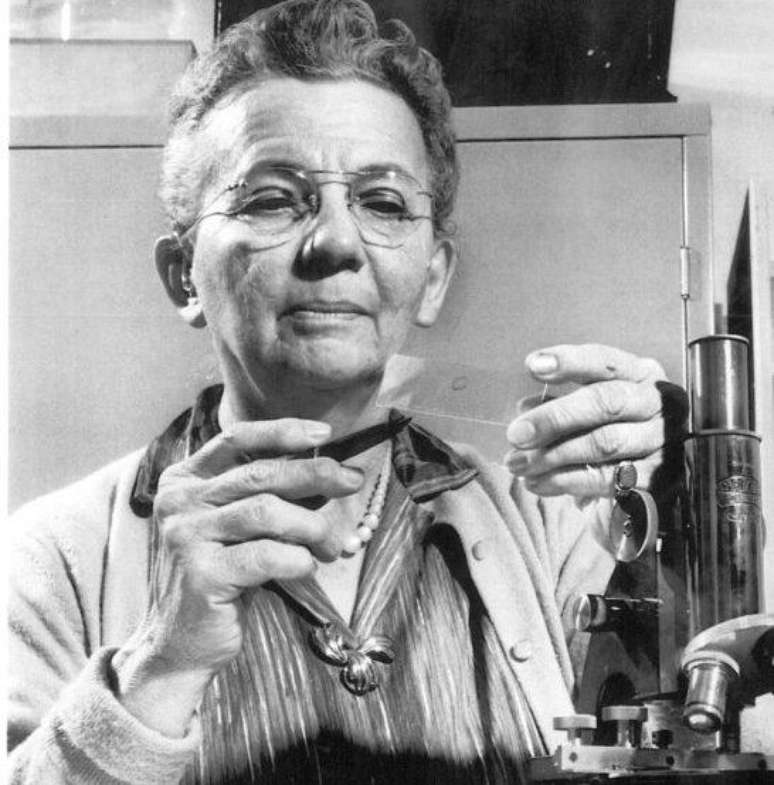

In the second half of the 20th century, Florence Seibert invented the first method of sterilizing an injection. Today if we don’t die after having an injection it’s thanks to horseshoe crabs, which are becoming extinct because of this.

Seibert, the visionary

In the 1930s, the American biochemist, born in Easton, Pennsylvania, worked on a method to eliminate bacterial contamination present in solutions intended for vaccines and other injections, as part of her postgraduate work.

Seibert noticed that tuberculosis patients suffered from sudden fevers during or after injections and intravenous treatments. After discovering which proteins caused illnesses due to bacterial contamination of the water used to prepare the solutions, Seibert invented a distillation device that prevented bacterial contamination. Thus the Pyrogen Test was born.

Pyrogens are particles that arise from viruses, bacteria, yeast, fungi or chemicals that can induce an inflammatory immune reaction when injected and metabolized into the human body.

For two decades, rabbits have been chosen as test subjects, which has had a significant impact on the safety of pharmaceutical and medical products and is the focus of contamination control.

From the 1950s onwards, ethical concerns arose regarding the inappropriate use of animals in laboratory experiments, as pyrogen testing involved subjecting rabbits to discomfort and, in some cases, suffering.

Bleeding at all costs

Rabbits were successfully replaced by crabs, better known as horseshoe crabs, as pathobiologist Frederik Bang and medical researcher Jack Levin realized that the blood of these animals clots more sensitively to the presence of bacterial endotoxins because carries a protein called amebocyanin. Therefore, the Limulus Test was created to extract the Limulus Sample Lysate (LAL) reagent.

As a result, academic researchers, biomedical companies, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have perfected LAL manufacturing and approved it as a new method for testing endotoxins in drugs. The problem is that, every year, half a million horseshoe crabs are caught so that 30% of their blood is drained in laboratories, before being returned alive (or not) to the ocean.

The harvesting of horseshoe crabs and their misuse for bait has grown as LAL production has increased since the 1990s. Regulation along the entire U.S. coast has been limited, making companies increasingly secretive and prone to resorting to illegal practices to obtain greater quantities of horseshoe crabs and their improper use as bait. Crabs. Records achieved by National Public Radio indicated that in some states, fishermen paid by bleeder companies handled crabs in ways that caused damage or violated harvest laws and were not punished.

Meanwhile, about 94% of migratory coastal birds in the Calidris hoary they have disappeared over the last 40 years, classified by the federal government as threatened with extinction. They depend on horseshoe crab eggs for food during spring, the main migratory season of the year, providing enough energy to complete their journey, which can range from the tip of South America to the Canadian Arctic.

The crab population has declined moderately along the Atlantic coast, where they are caught for bleeding and used as bait on a large scale. Around New England, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has determined that these animals are considered “vulnerable to extinction.”

Mafia industry

In the 1990s, researchers at the National University of Singapore invented the first process to create a synthetic endotoxin-sensing compound using horseshoe crab DNA and recombinant DNA technology. Thus, recombinant Factor C (rFc) emerged, an effort to try to rein in the fishing and biomedical industries, preventing the destruction of the horseshoe crab population.

Over time, several biomedical companies have produced their own versions of rFc, but LAL continues to be used because the United States Pharmacopeia (a quasi-regulatory organization that sets safety standards for medical products) considers rFc a “alternative” method of endotoxin detection, requiring case-by-case validation for use – a potentially time-consuming and expensive process.

Therefore, companies increasingly end up resorting to the traditional method of bleeding horseshoe crabs. Environmentalists want the Pharmacopoeia to certify the RFC for use in industry without the need for further testing or validation. LAL manufacturers are believed to be blocking approval of synthetic blood to protect their market, putting money before a limited resource and potentially irrecoverable environmental damage.

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.