In the past, codpieces were added to armor to protect the fertility of knights on the battlefield. But they soon began to be used to enhance and adorn men’s private parts.

Around the year 1536, the Swiss painter Hans Holbein the Younger was completing the drawing of Henry VIII’s horse in his famous painting of the King of England.

With a thin brush in his hands and a watercolor palette at his side, the artist encountered difficulty in giving the right emphasis to the volume of his client’s trousers.

It is often said that in Holbein’s drawing – a life-size sketch for a mural that once covered the entire wall of Whitehall Palace in London – the king appears majestic and virile.

Henry VIII’s feet are firmly planted some distance apart and his two hands rest suggestively below his waist. Everything seems to direct the viewer towards the king’s genitals, which are absurdly disproportionate.

A contemporary account states that the final painting left all who saw it “ashamed and crushed”.

For a brief moment in the Renaissance, between the invention of the microscope, printing press, and pencil (among many other technologies that underpinned modern society), upper-class men were more concerned with promoting another innovation: the codpiece .

These “beautiful personal penis palaces,” as one writer once called them, consisted of fabric pockets sewn onto the genitals and stuffed to form a bizarre array of suggestive shapes: spirals, spheres, and upside-down sausages. Some even had faces printed on them.

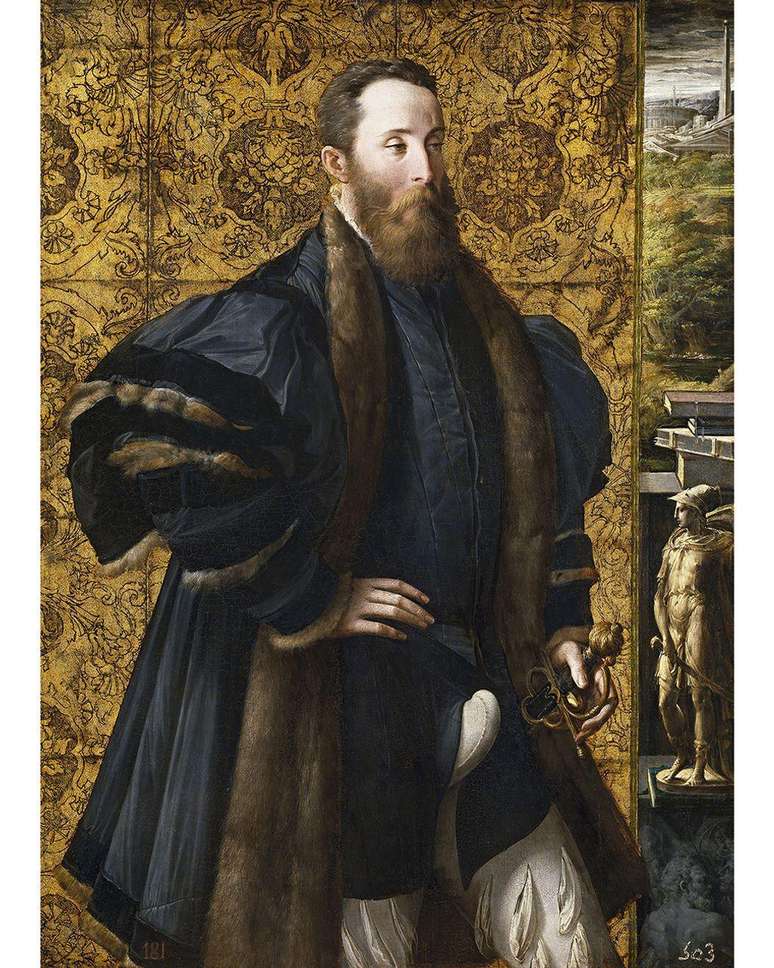

It was a rare opportunity for men to add a touch of style to their private parts. And many opted for packages in sumptuous fabrics, such as silk, velvet and satin, embellished with jewels, gold and beautiful bows, a true expression of male fertility.

But what were the braghetti for? And why did they disappear?

Discreet start

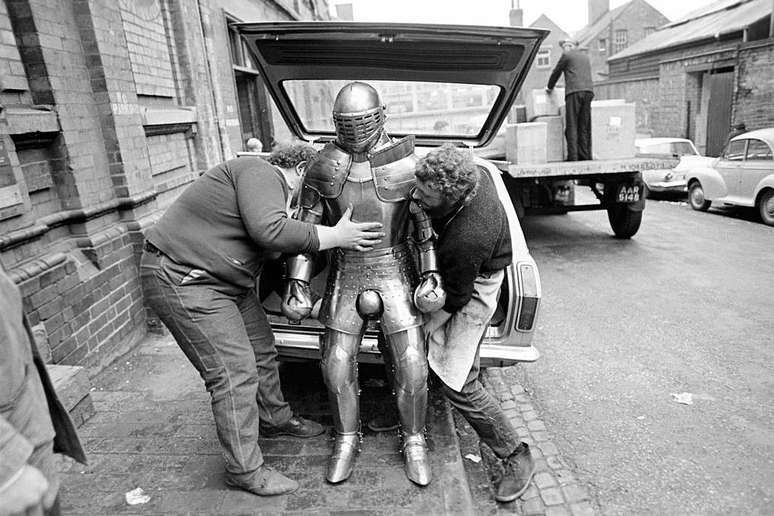

In the beginning, codpieces were made of steel and added to armor to help protect the fertility of knights on the battlefield. But they soon represented a practical solution to an annoying everyday problem of the time.

Until the late 15th century it was common for men to wear a long tunic or doublet – essentially a dress – with tights covering the legs. But fashion soon changed.

The gibbons gradually decreased in size over the years, until they became so short that they no longer covered their groins. This was especially dangerous since the tights worn by men at the time had the legs separated, leaving open spaces that could be quite revealing.

“Basically, you put one leg in one of the stockings and tied it to the doublet. And then you did the same with the other leg,” explains modern Italian historian Victoria Bartels of the Syracuse University Center in Florence, Italy.

But, with the trend of new, shorter versions of dresses, “there was kind of an area that needed to be covered,” according to her.

The problem was particularly illustrated in medieval poetry The Canterbury Tales. In the story’s prologue, a character known as “the person” complains:

“Unfortunately, some of them show the bulkiness of their forms and the horrible enlarged limbs, which resemble hernia disease.”

Open spaces have generated a moral panic. The priests feared that the new fashion would become irresistible to “sodomites” and lead to the corruption of young people.

The first codpieces were loose triangles of fabric that were inserted to cover the openings between each leg of clothing. But it didn’t take long before men took advantage of this new garment and began to include padding.

Two decades later, the loose triangles had transformed into phallic objects of gigantic proportions.

The first would-be conquerors filled their breeches with horsehair, cloth and straw. Sometimes they hid useful items such as handkerchiefs and money.

Bartels even found news of its use to preserve dried flowers, but only in satirical texts.

From the streets of Florence, where they were known as bagto Paris, where they received their French name braguettesyoung men showed off their fake genitals, attracting stares wherever they went.

What began as a secretive tool began to be used to the opposite effect.

And the symbolism of this baggy piece of clothing wasn’t limited to the Renaissance men who wore it. The very English word for this – code – comes from “cod,” which in Old English meant “scrotum.”

A satirical text found by Bartels compared the protection offered by codpieces (especially on armour) to that provided by walnut shells and seeds. After all, just like the “braguettes naturelles” (natural brachettes), they helped ensure the propagation of the new generation.

Henry VIII’s drama of having a legitimate heir led him to create a new branch of Christianity. His search for fertility also led the English king to make maximum use of the figurative associations of the codpiece.

The mural in the Palace of Whitehall was destroyed by fire in 1698, but the original design survived and led other artists to copy it. Therefore, the codpiece used by the king can still be seen in dozens of paintings today, sending the message to the beholder that Henry VIII was more than capable of producing an heir.

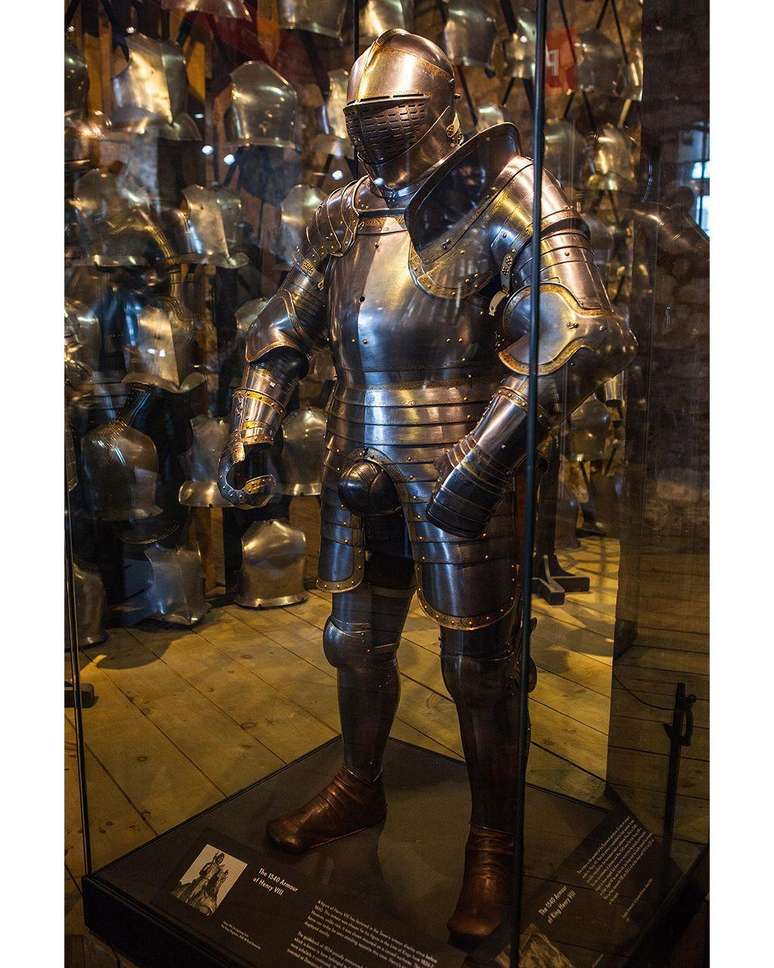

Two hundred years after his death, admirers could still visit the statue of Henry VIII in the Tower of London and marvel at its fertility.

In the work, a painted wooden effigy was adorned with a billowing cloth cape and had a secret mechanism that revealed a swinging codpiece.

“If you press a spot on the floor with your feet, you will see something surprising in this figure, but I will say no more,” one visitor wrote, according to the book. Push: a spasmodic pictorial history of the codpiece in art (“Impulse: a spasmodic pictorial history of the codpiece in art”, in free translation).

Women even used to insert pins into the effigy, in a sort of ritual to help them have children.

At that time, such bold displays of virility were not uncommon.

On the cast iron portal of the Colleoni Chapel in Bergamo, Italy, built in the late 15th century, is the Colleoni coat of arms. Above it are three comma-like shapes.

These shapes represent the testicles. It is believed that they were included to show the male strength of the lineage.

There is also a similarity between the surname Colleoni and the Italian expression balls, which refers to the testicles.

Men also wore ornaments in the groin area to convey their military courage.

Initially, codpieces were actually added to the armor. But Bartels explains that the rise of these pieces coincided with the Italian Wars (1494-1559).

During these conflicts, mercenaries from northern Europe fought on behalf of Spain, France and Italy.

One of the benefits soldiers received was exemption from the Sumptuary Laws, which determined the degree to which any social group could become unruly. And they took advantage of this opportunity in clothing.

“They dressed super flashy… they wore these huge pantaloons,” according to Bartels. And so another link was formed between the codpiece and military culture.

Even for his contemporaries, these open and overt displays of masculinity were often the subject of great ridicule.

According to historian Will Fisher, in the book The materialization of gender in early modern English literature and culture (“Materialization of Gender in Early Modern English Culture and Literature,” in free translation), humorists of the time thrilled their audiences with suggestive scenes in which a character seemed about to reveal his genitals… until until they got something unexpected out of their pants, like an orange.

Other unusual items found in fictional codpieces included “poems, bottles, napkins, guns, hair, and even mirrors.”

The codpiece was already in decline at the end of the 16th century, when according to Victoria Bartels available sources began to define it as something out of fashion.

Interestingly, just before these bulky accessories began to disappear, they began to shrink to tiny proportions.

“You start to see another fashion trend called ‘pea belly,’” Bartels explains. They were enlarged, unpadded jackets that were worn over the shirt, creating a bulge in the belly area. “It seems ridiculous to modern eyes.”

Once upon a time they were accompanied by padded shorts or even in the form of skirts. Bartels explains that this combination highlighted the same region of the body as the codpiece, as both incorporated the genitals.

Currently, few “pea bellies” still survive.

Among those that have been preserved are bulges of metal armor, a wool and velvet set that belonged to a Swedish count and his sons, and a set of pieces that are part of the Museum of London, initially classified as shoulder cushions by a Victorian curator, according to historian Lucy Worsley.

In addition to these remaining objects, we can observe the priapic grandeur of this lost garment only in paintings and sculptures of the time.

But although authentic Renaissance codpieces are now rare, public enthusiasm for them has not entirely disappeared.

In the 70s and 80s, rock bands like Jethro Tull and Kiss began to surprise the public with versions of leopard-print, leather, studded or decorated with demon faces.

The band Kiss even had its own seamstress until the band folded last year.

Knickers have also made a comeback in high fashion, as part of a trend called “Tudor power dressing”, and in historical television series, such as the British one Hall of Wolves.

But modern manufacturers have not yet managed to make codpieces as large as those of the past.

Read the original version of this report (in English) on the website BBCFuture.

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.

![It All Begins Here: What’s in store for Thursday 16 October 2025 Episode 1286 [SPOILERS] It All Begins Here: What’s in store for Thursday 16 October 2025 Episode 1286 [SPOILERS]](https://fr.web.img3.acsta.net/img/7d/99/7d99acbb3327f48a72b40f684092775e.jpg)

-qe1jxfyoo3eh.JPG)