Research shows that men, especially low-income men, are more susceptible to what sociologists call “social infertility.”

Fertility rates are plummeting around the world, even faster than expected. China is experiencing record birth rates. And in Latin America, official birth statistics are well below forecasts in several countries.

In the Middle East and North Africa, birth rates are also falling more dramatically than expected. This is a result of people having fewer children, but also because, in almost every country in the world, more and more people simply don’t have children.

Isabel created the group Nunca Madres after the end of an unpleasant relationship in her early thirties, which led her to the conclusion that she did not want to have children.

She faces criticism for this choice every day, and not just in Colombia, where she lives.

“What I hear most is, ‘You’ll regret it, you’re selfish. Who will take care of you when you’re old?'” he reports.

For Isabel, not having children is a choice. For others, it is the result of biological infertility. And for many more people, it’s a confluence of factors that means a person doesn’t have the child they want – what sociologists call “social infertility.”

Recent research has shown that men are more likely to be unable to have children even if they want to, especially low-income men.

A 2021 study in Norway found that the rate of childlessness among men was 72% among the 5% with the lowest incomes, but only 11% among those with the highest incomes – a widening disparity by almost 20 percentage points over the last 30 years.

When Robin Hadley was in his 30s, he desperately wanted to be a father. He had not attended university, but worked as a technical photographer in a university laboratory in the north of England.

Before that, he had married and tried to have a child with his wife, but they eventually divorced.

He was saddled with a mortgage that he struggled to pay and couldn’t afford to go out much. Therefore, dating was a challenge. When her friends and colleagues became parents, she felt a sense of loss.

“Baby birthday cards or baby showers, they all remind you of what you are not — and what you should be. There’s a pain associated with that,” she says.

His experience inspired him to write a book about childless men. When he wrote it, he realized that he had been influenced by “all the factors that impact fertility outcomes: economic, biological, temporal, and relational choices.”

And he noticed that most of the studies on aging and reproduction he read were missing childless men – they were also almost completely absent from the national statistics of most countries.

The rise of “social infertility”

There are several reasons for social infertility, such as lack of resources to have a child or not finding the right person at the right time.

But at the root of all this is another issue, says Anna Rotkirch, a sociologist and demographer at the Finnish Institute for Population Research who has been studying fertility intentions in Europe and Finland for more than 20 years. He observed a profound change in the way we view children.

Outside of Asia, Finland has one of the highest childless mortality rates in the world. However, in the 1990s and early 2000s, the country was celebrated for combating fertility decline with globally recognized child-friendly policies. Parental leave is generous, daycare is more accessible, and men and women have more equal participation in domestic work.

Since 2010, however, fertility rates in the country have fallen by almost a third.

Rotkirch explains that, like marriage, having a child was once seen as a milestone event, something young people did as they began their adult lives. It is now seen as a culminating event: what you do when the other goals are achieved.

“It seems that people of all classes find that having a child increases uncertainty in their lives,” Rotkirch notes.

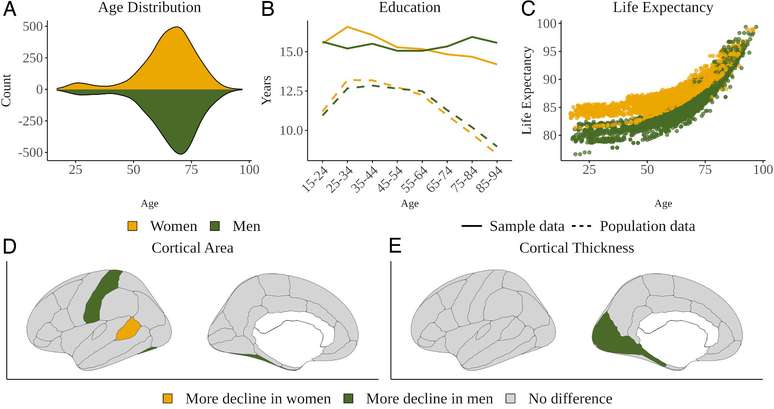

In Finland, it found that wealthier women are less likely to become involuntarily childless. On the other hand, low-income men are more likely to not have the children they want.

This is a big change from the past: previously, people from poorer families tended to transition into adulthood earlier: they dropped out of school, found jobs and started families at a young age.

A crisis of masculinity

For men, financial uncertainty has a compounding impact that further reduces the likelihood of having children. This has been called the “selection effect” by sociologists, where women tend to look for someone of the same social class or higher when choosing a partner.

“I see he was out of my league intellectually and in terms of trust,” Robin Hadley says of the relationship that ended when she was younger.

“I think, in hindsight, the selection effect may have been a factor.”

When he was in his late 40s, he met his now-wife, who helped him go to college and earn a doctorate. “I wouldn’t be where I am now if it weren’t for her.” By the time they thought about having children, they were already over 40 and it was too late.

In 70% of the world’s countries, women surpass men in terms of educational attainment, which has led to what Yale University sociologist Marcia Inhorn calls mating gap (“disparity of love”). In Europe, this has led to men without university degrees becoming the group most likely to be childless.

Invisible men

Most countries do not have reliable data on male fertility because they only consider the mother’s fertility history when registering a birth. This means that childless men do not exist as a recognized “category”.

Some Nordic countries, however, consider both. The Norwegian study, which identified the huge disparity in procreation between rich and poor men, said countless men are being “left behind”.

The role of men in declining birth rates is often ignored, says Vincent Straub, who studies male health and fertility at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.

He is interested in the role of “male malaise” in fertility decline: the disorientation felt by young people as women gain power in society and their expectations of virility and masculinity change.

This has also been called the “crisis of masculinity”, represented by the popularity of right-wing anti-feminists such as controversial influencer Andrew Tate.

“Men with lower levels of education are in a much worse situation than in previous decades,” Straub tells the BBC.

In many high- and middle-income countries, technological advances have made manual work less valued and more insecure, increasing the disparity between those with college degrees and those without.

It has also increased the “love gap” and has a significant impact on men’s health.

“Substance abuse is increasing globally, and is highest among men of reproductive age, both in Africa and in South and Central America.”

All of this has an impact on social and biological fertility. “I feel like there’s a missing connection between fertility and these types of social and cultural changes,” she says.

And this can have a fundamental impact on men’s physical and mental health. “Single men tend to have worse health than men who are in relationships,” Straub notes.

Straub and Hadley found that the fertility debate focuses almost entirely on women. And all the policies created to address it are missing half the picture.

Straub believes we should focus on fertility as a men’s health issue (too?) — and discuss the benefits that caring for a child offers fathers.

“In the European Union, only one man in 100 interrupts his career to care for a child; among women, one in three does so,” he says. This happens despite countless evidence that caring for a child is good for men’s health.

Through her organization Nunca Madres, Isabel met with some representatives of a large international bank in Mexico. They told her that although they had offered six weeks of paternity leave, no men had taken the leave.

“They think this is a woman’s job, and that’s how men feel in Latin America,” she says.

“We also need better data,” says Robin Hadley. Until we record men’s fertility, we won’t be able to fully understand it, nor the effect it has on their physical and mental health.

And the invisibility of men in fertility debates goes beyond reality. While there is more awareness today that young women need to think about declining fertility, this is not a conversation that exists among young men.

Men have a biological clock, too, Hadley says, citing research showing that sperm effectiveness declines after age 35.

Making this invisible group visible is one way to address social infertility. Another might be expanding the definition of fatherhood.

All researchers who have commented on the issue of childlessness have been keen to point out that childless people still have a vital role to play in raising them.

Behavioral ecologists call this alloparenting, explains Anna Rotkirch. For much of human evolution, a child had more than a dozen caregivers.

One of the childless men Hadley spoke to for his research commented on a family he regularly met at the local soccer club. For a school project the two boys needed a grandfather. But they didn’t have any.

He took on the role of their stepfather and for many years, when they saw him at football, they said: “Hi, grandfather.” It was a wonderful feeling to be recognized in this way, according to him.

“I think most people without children are actually involved in this type of care, it’s just invisible,” Rotkirch says.

“It’s not on the birth certificates, but it’s very important.”

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.