Since July, Santiago Schnell will be the president of Dartmouth College, one of the eight elite universities that make up the Ivy League in the United States.

When Santiago Schnell was large enough to decide which career to pursue, he already suffered from autoimmune diseases, including cancer.

During the elementary school, he was divided between two passions: the father’s computers and the experiments of natural sciences of the neighbor, Professor Serafin Mazparote, author of the biology textbooks used in Venezuela.

But between father and teacher Mazpartate, computers and natural sciences, another uncontrollable force interfered with their study routine: the battle of the body against themselves.

“Since I was born, I had fragile health: terrible allergies, will to go to the bathroom that I could not control. And nobody understood what was happening to me,” says Schnell, 53 years old, while preparing to become president of Dartmouth College on July 1.

Dartmouth is located in New Hampshire on the eastern coast of the United States. It is one of the eight universities that make up the Ivy League, together with Harvard, Yale, Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Pennsylvania and Princeton, a group of private higher education institutes recognized for their academic excellence.

A computer and a teacher

While his mother visited the doctors of Caracas for a diagnosis, his father tried to familiarize Schnell with the calculation, convinced that it would have been the discipline of the future.

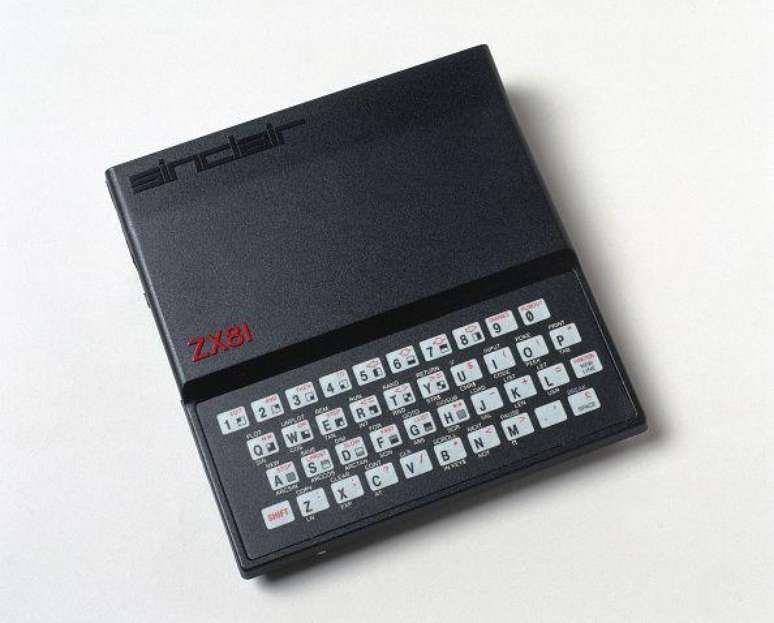

“My father gave me a Sinclair Zx 81, an English car that was one of the first personal computers, long before Apple or IBM, so I was able to learn to program and think logically.”

It was 1981 and Schnell was 10 years old.

“Almost nobody had a personal computer at home at that moment, much less in Caracas. He caused a very fast change in my life because I started thinking about algorithmic procedures to solve problems.”

During the family tours, Schnell abandoned Sinclair Zx 81 and accompanied Professor Mazparte to shipments to collect samples from his experiments and take photographs to illustrate his books.

“I was incredibly surprised by his ability to predict things by doing an unexpected observation. For example, we walked in the jungle and, when he saw some ants, he could predict that, at 10 or 20 meters away, we would find the type of bird that aente those ants.”

“Having this mental ability to see more than anyone else, being a Sherlock Holmes of nature, combined with my father’s computers, aroused my passion for science.”

Unexpected diagnostics

But when Schnell came to high school, he was not tormented only by allergies and stomach pain. He also developed reddish crusts on the scalp, which scratched and wounded, and eventually released white flakes that seemed dandruff.

The doctors diagnosed him with psoriasis, a chronic autoimmune disease that causes an abnormal increase in the production of skin cells. The unexpected effect was that the treatment that suppressed its immune system led him to develop cancer at the age of 15.

“Autoimmune diseases have become even more aggressive after cancer. I have not lived to tell the story, but health problems only increased my curiosity for the medical sciences.”

In search of a diagnosis that explained allergies, psoriasis and cancer, the doctors discovered Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammation of the intestine that constantly forced it to the bathroom.

After passing cancer, Schnell acquired a new understanding of his purpose and interest. “My health was so tired that I thought perhaps, with my mind, I could help you.”

The first laboratory

In 1991, Schnell began his degree in Biology at Simón Bolivar University, created to form engineers, architects and scientists to participate in important Venezuela development projects such as Guri Hydroelectric and Caracas Metro.

In his free time among the lessons, he visited the Institute of Advanced Studies (Idea), a center dedicated to scientific and technological innovation, to which Schnell could walk in about 15 minutes from Simon Bolívar University.

To gain access to the laboratory, the doctor and the Venezuelan researcher Raimundo Villegas, who had been minister of science and technology, launched a challenge: cleaning the tubes of the tests, pipettes and other glass tools for four months.

“Villegas said to me: ‘If you can do this well, exceptionally, we will give you something different,” recalls Schnell.

“This experience taught me to pay attention to details,” he said in a video chain with the BBC Mundo. “Glass cleaning is perhaps one of the most important tasks, because molecular biology experiments fail if there is contamination in the glass.”

In the laboratory, he also learned to pursue his ideas without copying those of others, even if he is often called “crazy”.

“Nobody cares if we scientists make mistakes. We formulate a hypothesis, we do the experiment and, if we do not work, we start again. What do I have to lose? Let me fail.”

Although Schnell was just a university student, Villegas allowed him to participate in research on the development of the brain and artificial insemination to create laboratory embryos.

“In this process, I realized that I liked computational measurements. But to dedicate myself to it, I needed someone who taught me to think as theorist.”

The charm of enzymes

Villegas indicated Schnell to Claudio Mendoza, a computer physicist who worked at the Venezuelan Institute for scientific research (Ivic), an organization that coordinated several centers dedicated to the basic sciences and applied to Venezuela.

From an astrophysical point of view, Mendoza participated in projects to study “stars, planets and cosmic dust, to understand how the universe and life originated from a chemical perspective in space”, explains Schnell.

From this collaboration the Schnell-Mandoza equation came from this collaboration, a mathematical formula that facilitates the study of biochemical processes through enzymes, proteins that accelerate chemical reactions in living organisms.

“We simplify the speed with which enzymatic reactions can be measured both in the laboratory and in the clinic,” says Schnell.

“Claudio taught me that there must be beauty in computational mathematical models, that the equation must be seen as a universal law because it is beautiful and simple.”

While his allergies and his pain worsened, Schnell decided to devote himself to mathematical and computational biology, a discipline that did not formally exist in Venezuela or in most universities in the world.

However, in the late 90s, there was a center dedicated to the study of this theme at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Although they had no contacts there, Mendoza promised Schnell who would help him get to Europe.

Continuum

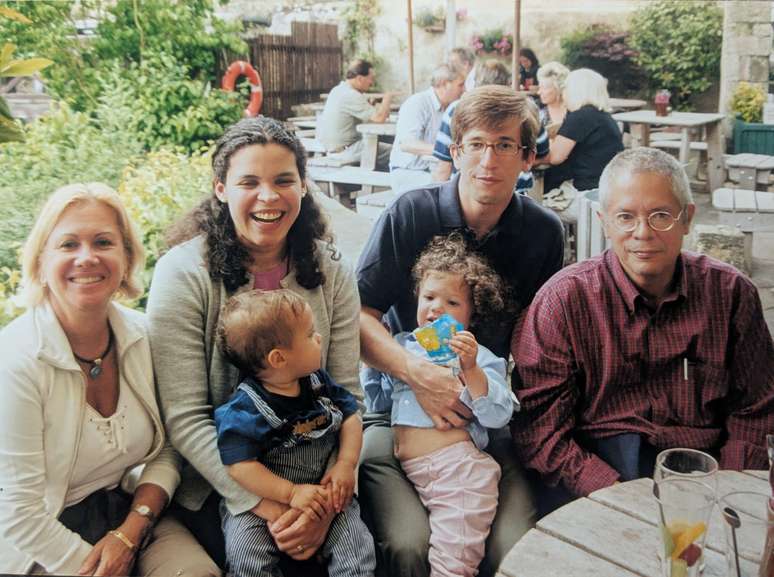

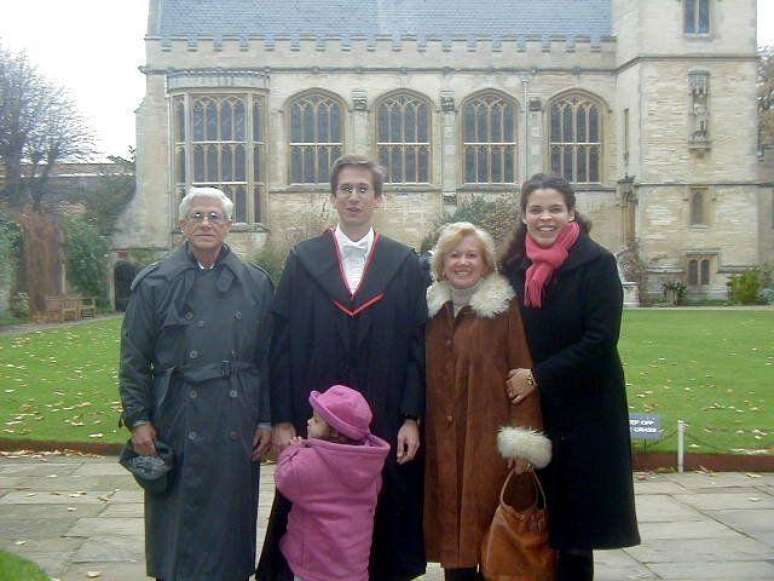

In order to expand the scope of the equation he had projected with Mendoza, Schnell arrived in Oxford in 1998, where he met Philip Maini, a British mathematician who was starting his career as a mathematical biology teacher and was willing to be his doctoral thesis consultant.

“I felt completely inappropriate because I saw these people with a level of cultural and scientific training that I didn’t have. That’s why I can’t believe that I will be a rector of a university of the Ivy League.”

During the 27 years of Schnell’s academic career in Europe and the United States, he focused on the continuum between health and illness, a model that says that the two phases are not opposite, but part of a spectrum.

“With all the technology we have, we are not yet able to measure the continuum,” he says. “For example, having a smartwatch capable of measuring blood pressure and predicting that you will have an emergency before it happens.”

Schnell would like to have this technology to avoid the worst outbreaks of Crohn’s disease when he went to the bathroom 40 times a day in the middle of his academic days as a professor at the University of Michigan.

Or the surgery that has removed its large intestine, which now means that it downloads its waste in a bag that transports inside the shirt.

Or the traces of Haddad syndrome, a rare genetic disease that forces him to sleep with artificial breathing every night to avoid suffocating.

Or autoimmune arthritis that causes joint inflammation, especially when playing tennis.

Although he has not studied diagnostic methods relating to diseases that suffers, he underlines the importance of the activities and results that fill the 50 pages of his curriculum.

“Where I have greater recognition is in the development of mathematical equations, software and statistical techniques so that people can measure, both in the laboratory and clinical, proportional health factors such as the efficiency of enzymes that can cause diseases when they fail.”

Dartmouth’s challenge

Santiago Schnell does not consider the decisions of President Donald Trump against the University of Harvard or the suspension of visas to foreign students in the United States the greatest challenge that will face the presidency of Dartmouth University.

He is convinced that his biggest challenge will be to help restore the trust of American society in scientists.

“The notion of neutrality and which college teachers and researchers are public employees have been lost. We must return to this notion; we are here to improve the life of the population through the education we offer and the research we do”.

He has not been in Venezuela for years, but when he thinks of Simon Bolivar University, devastated for a decade of humanitarian emergency, he feels grateful.

“That’s where I learned to think scientifically and persist in my ideas. The legacy of the University of Simón Bolivar accompanies me every day.”

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.