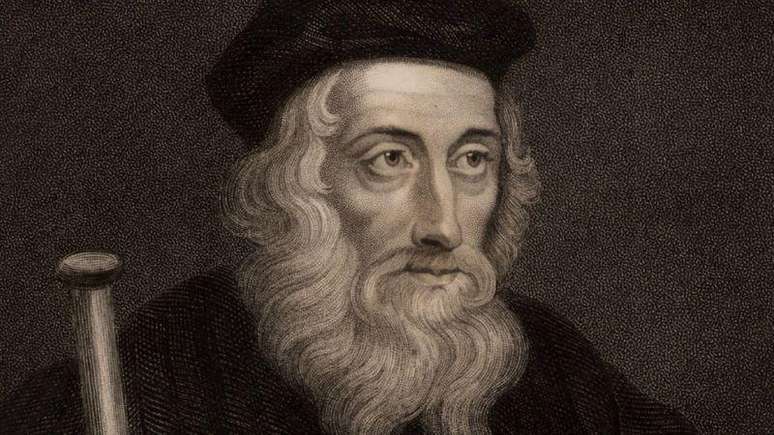

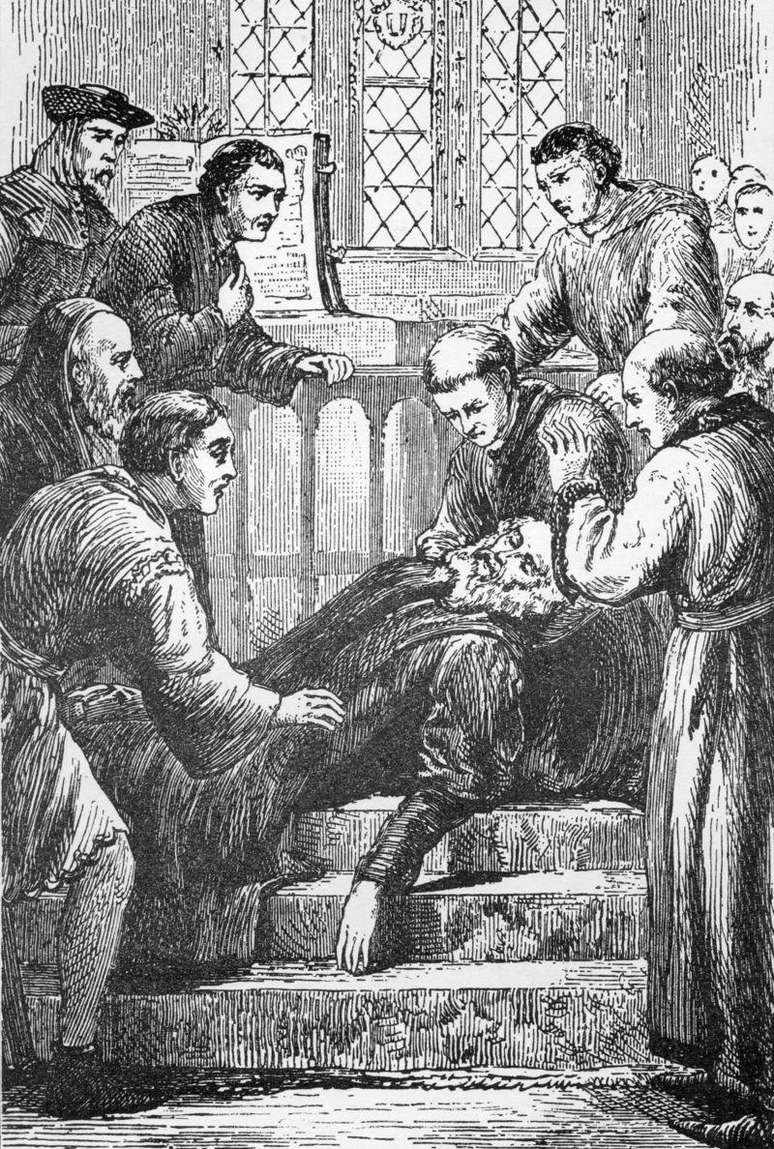

The Catholic Church, which banned the translation of the sacred text, punished him for his heresies nearly four decades after his death.

John Wycliffe’s death sentence, in the early 15th century, occurred when the accused had been dead for 30 years.

However, more than ten years after the conviction, his body was reportedly removed from the grave, the remains ended up burned and the ashes thrown into the River Swift in central England.

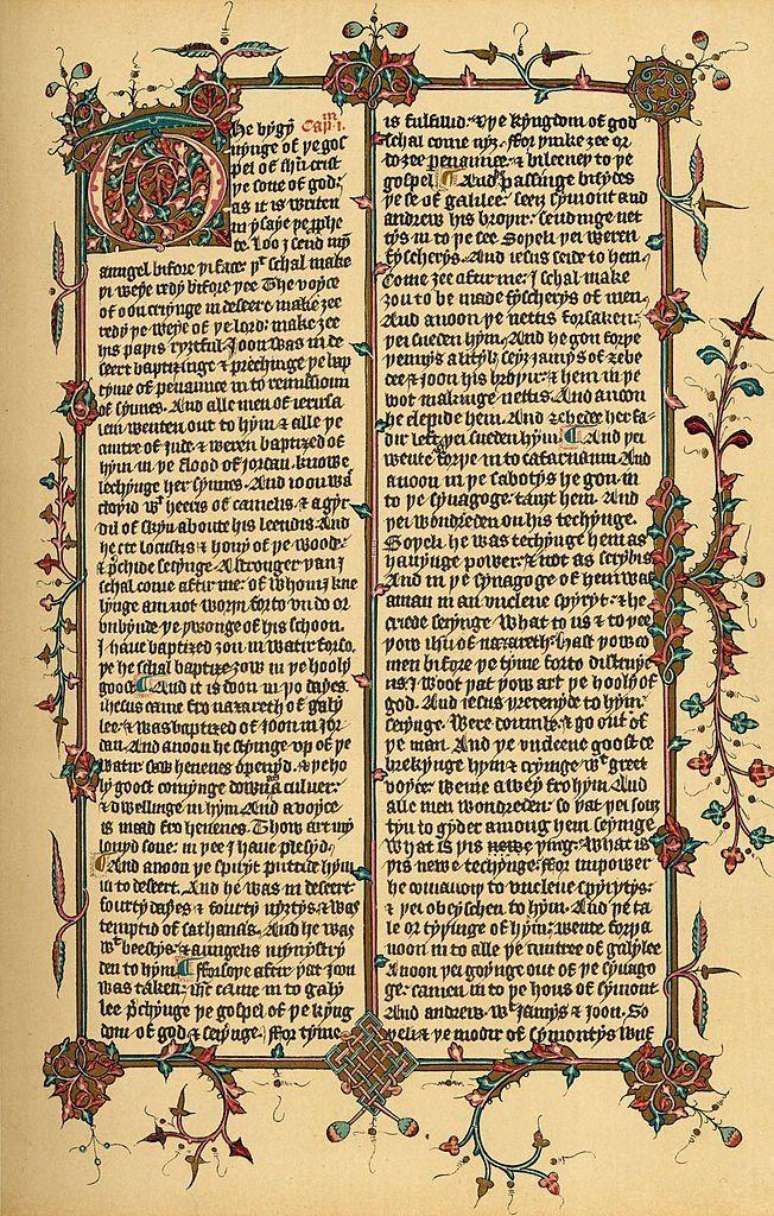

This is what happened to this medieval English philosopher and theologian, who is credited with proposing the first complete translation of the Bible from Latin into the English language, which was completely forbidden by the Church.

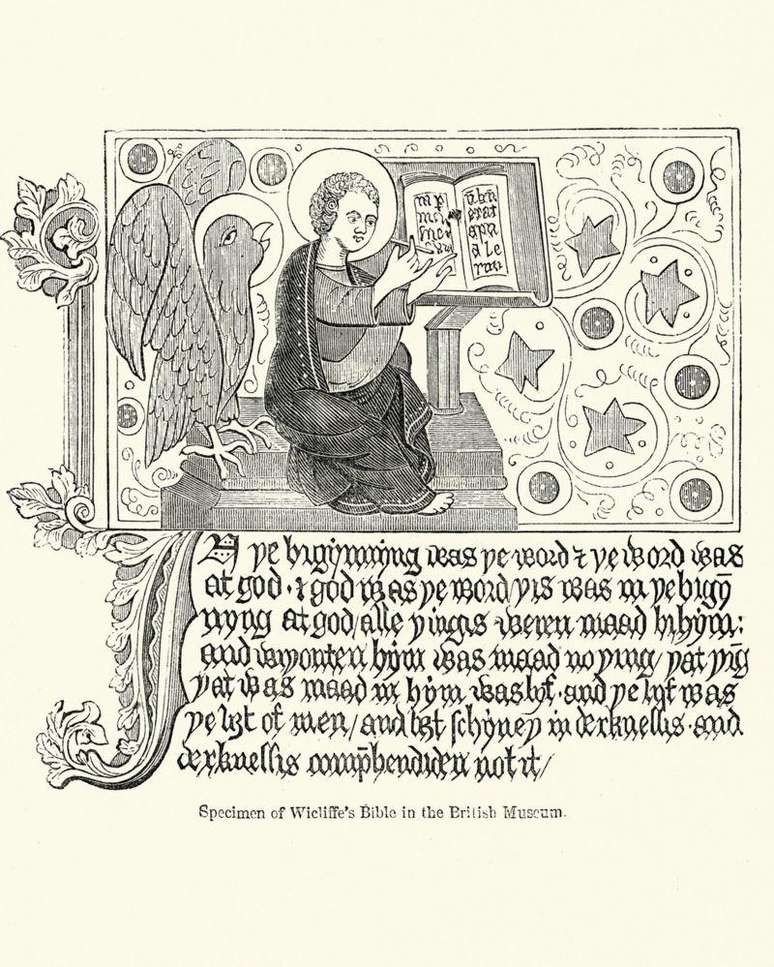

This translation, known today as the Wycliffe Bible, was just one of many questions the philosopher raised against it modus operandi of the Catholic Church. His ideas inspired a movement of dissent considered heretical and laid the foundations for a reform (or revolution) that occurred more than a century after his death.

Wycliffe’s argument was that “the Church that existed in the late fourteenth century was not an accurate reflection of the Church that could be traced in the Bible, the Gospels, the Epistles and Acts,” explained Anne Hudson, professor emerita of English medieval at the University of Oxford. , UK, in a BBC program about Wycliffe.

According to Hudson, the medieval philosopher was by no means a fundamentalist. On the contrary, he elaborated his thoughts on him starting from the discrepancy he saw between the material wealth of the Church in relation to the social reality of the time.

the world around

In the same programme, philosopher Anthony Kenny, of Balliol College, Oxford University, recalled that Wycliffe’s early philosophical writings and teachings reflect nothing heterodox or heretical — although there was already a tendency in this reasoning that was beginning to define this future path.

“It was extraordinarily realistic,” described Kenny. “And he drew political conclusions from that realism.”

According to the specialist, the universal was more important than the individual, and the commonalities were more valuable than the particular characteristics of a person.

“Then he fell into a theoretical communism based on realism,” says Kenny.

Wycliffe began thinking more about these ideas and writing about them at a time when not only was the Church being questioned, but society as a whole was being debated.

“There’s a backstory to all of this,” contextualizes Rob Luton, a professor of medieval history at the University of Nottingham in the UK.

“There is the Avignon papacy, when the pope’s residence was transferred to France, which raised many questions about authority within the Church itself.”

“Like the rapid social change that occurred after the Black Death, which challenged the traditional ways of society and questioned how one could act as a Christian in the face of these changes,” he adds.

Another striking fact of this period was the Hundred Years War, which pitted England against France and the presence of ecclesiastical authority on Gallic soil.

For Wycliffe it made no sense that the kingdom and nobility of England should respond to and financially support an authority located in enemy territory.

more radical

Wycliffe even questioned the doctrine of transubstantiation – the ability to transform bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ – which was (and continues to be) a core part of Catholicism.

The philosopher did not deny the presence of Christ, but questioned the need for the sacrament.

“This was very important for the clergy, because this is one of the greatest powers that priests have. By denying the Eucharist, this power would be taken away from them”, underlines Professor Kenny.

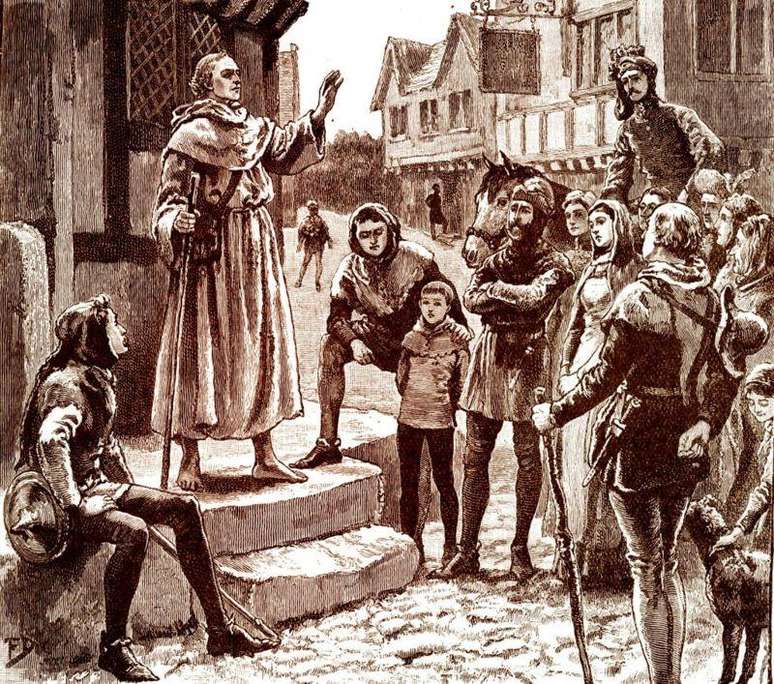

An important aspect of Wycliffe’s theories is that he wrote them in English so that they were accessible and more people could discuss them.

This, incidentally, is the same reason he insisted on translating the Bible: the idea was to reinforce the sacred text’s importance as the ultimate authority for Christians.

Inheritance

And although this translated version of the Bible has been attributed to him, his name does not appear in the text.

“I have to point out that this must have been a collaborative effort,” Hudson points out.

It was therefore a long and expensive process, considering that printing had not yet been invented at the time – and today about 300 copies of Wycliffe’s Bible are known.

Many copies were produced and distributed long after Wycliffe’s death in 1384 by an army of followers of his doctrines who formed a movement known as the “Lollars”.

These ideas have managed to gain strength thanks to the passivity of a Church distracted by internal problems, in a period that has had up to three popes at the same time.

Indeed, such was Wycliffe’s influence on other great theologians – such as the Czech Jan Hus and later reformers – that the philosopher is regarded as the “morning star”, as one of the forerunners of the Protestant Reformation.

However, the Church tried to solve the problems in 1414 through the Council of Constance, a kind of emergency summit formed to try to unify the papacy.

And one of the council’s first resolutions was to attack those who questioned the authority of the Catholic leadership.

Hus was sentenced to death and immediately executed, while Wycliffe was found guilty of heresy. The “Lollari” began to be chased.

Although it took until 1428 for the sentence against Wycliffe to be carried out, his remains were exhumed, burned and thrown into a river.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.