Under Lula, the minimum wage becomes a real gain again, after the stagnation of the Temer and Bolsonaro governments. But the floor at R$ 1,320 buys even fewer basic food baskets than in 2018.

The new minimum wage of R$ 1,320 went into effect this Monday (01/05), representing an increase of 1.4% or R$ 18 compared to the value of R$ 1,302 in force since January 1st.

Adjustment above inflation had been one of the electoral promises of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT), who thus resumes the appreciation of the minimum wage, one of the hallmarks of his first two terms.

But how much has the minimum wage appreciated in every government since the end of hyperinflation with the approval of the Real Plan?

And what is the impact of this year’s adjustment and that planned for 2024 on general government accounts?

We asked economists Daniel Duque, researcher at Ibre-FGV (Brazilian Institute of Economics of the Getulio Vargas Foundation), and Vilma Pinto, director of the IFI (Independent Fiscal Institution) of the Federal Senate.

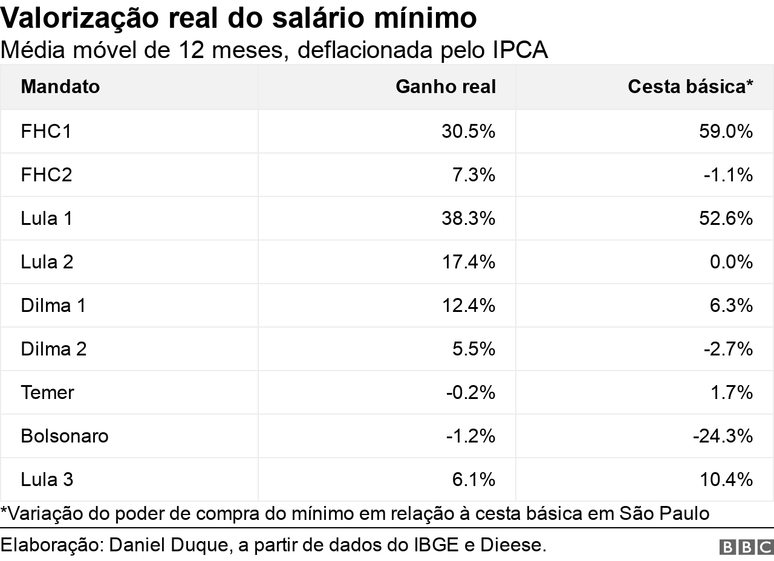

How valued is the minimum wage in every government

When Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB) assumed the presidency in 1995, the minimum wage was R$70 and would reach R$240 by the end of his second term in 2002.

Under Lula, it went from R$240 to R$545 in eight years, between 2003 and 2010. Under Dilma Rousseff (PT), it went from R$622 to R$880, in just over five years of her mandate, interrupted by the impeachment.

Michel Temer (MDB) took over the government with a minimum of R$ 880 and handed over R$ 954. Under Jair Bolsonaro (PL), the amount ranged from R$ 998 to R$ 1,212.

Now, during Lula’s third term, the low started in January at R$1,302 and rose to R$1,320 in May.

But, to evaluate how much the minimum has been appreciated in each government, it is not enough to look at the nominal values. Inflation must be discounted for each period.

To make this calculation, FGV’s Daniel Duque deflated minimum wage values from the HICP, the country’s official inflation index.

And what the data shows is that the low appreciated 30.5% in FHC’s first term and 7.3% in the second, for a total of 40% real appreciation in the toucan’s eight years.

Lula has recorded the greatest appreciation among the presidents who have governed the country since hyperinflation. In his first term, the minimum appreciation was 38.3% and in the second, 17.4%, totaling 62.4% gains above inflation in eight years.

In the Dilma government, with the country’s growth losing momentum, real increases in the minimum wage also lose strength: they were 12.4% in the first term of the PT and 5.5% in the second, up to 18.5% in just over five years in office, until his impeachment.

Under Temer and Bolsonaro, the country abandoned the policy of real appreciation of the minimum, starting to adjust the basic salary only for inflation.

As a result, the floor stagnated, recording a negative change of 0.2% in just over two years of management of the emedebista and a real devaluation of 1.2% in Bolsonaro’s four-year period.

Now, with the two adjustments already announced by Lula in 2023, the minimum real gain has returned: 6.1% until May, considering the inflation forecast for the current month in the Focus bulletin.

Purchasing power in relation to the basic food basket

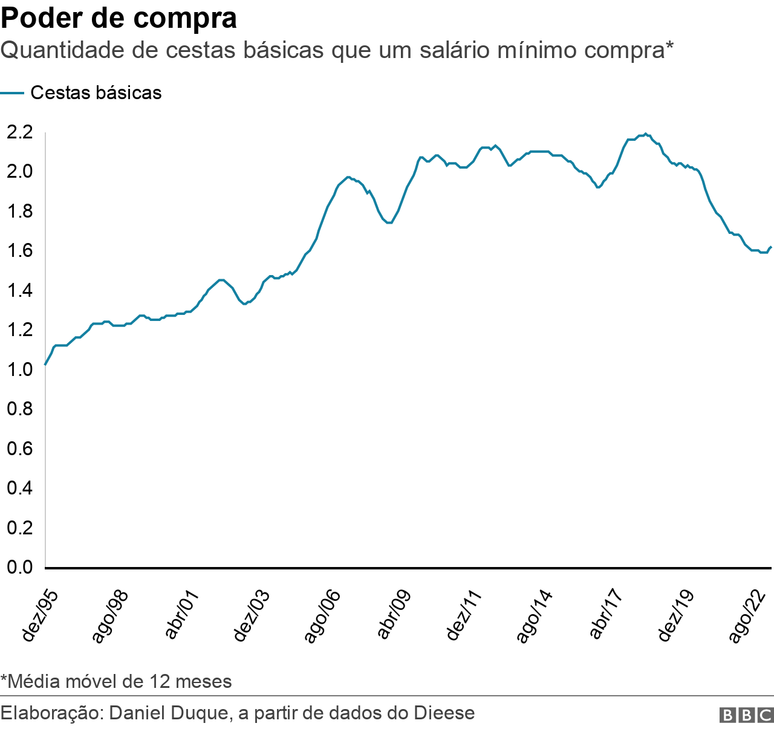

Another way to assess what has happened to the minimum wage in each government is to look at the purchasing power of the minimum wage in relation to the basic food basket.

Using the value of the basic food basket in São Paulo calculated by Dieese (Inter-union Department of Statistics and Socio-Economic Studies), Duque notes that the purchasing power of the minimum wage has grown by 57.4% in both FHC terms; 52.7% under eight years of Lula; only 3.4% in Dilma administrations; 1.7% under Temer; plummeting by 24.3% during the four years of Bolsonaro’s rule, amid sharp increases in food prices over the period.

With the adjustments announced by Lula, and in consideration of the expected value for the basic basket in April and May, the purchasing power of the minimum with respect to the basic basket grows again this year, by 10.4%.

Even so, the minimum wage of R$1,320 currently buys only about 1.6 basic baskets, still below the 2.2 baskets that the minimum could buy in August 2018, the high point of the power of purchase of the floor with respect to the basic basket, recorded during the Temer government.

What happened in every government

“The policy of valorising the minimum wage has essentially always had two vectors, very intertwined: the economic situation and the fiscal situation of the country”, observes Duque.

The economist recalls that, in the first term of FHC, there was a combination of good economic growth, with inflation under control. Even the minimum wage has been greatly undervalued, after 20 years of high inflation and disproportionate adjustments.

“There was a lot of room to readjust, and the overvalued real contributed to lower food inflation, which also increased the purchasing power of the wage,” he says.

In the second FHC administration, the scenario became more complicated, with lower growth and a worsening of the public accounts situation. In 1999, the so-called macroeconomic tripod was implemented, a set of measures combining floating exchange rates, inflation targets and fiscal targets.

“The greater fiscal control has put pressure on not to have so many readjustments of the minimum [já que o salário base serve de referência para gastos públicos como aposentadorias, benefícios sociais e salários do funcionalismo]. There hasn’t been a real loss, but there hasn’t been much appreciation over the period either,” Duque says.

In a scenario of recovery of economic growth, in his first mandate Lula achieved the maximum valorisation of the minimum of the post-Piano Reale period.

In 2007, this valuation policy was consolidated into a standard, which envisaged the annual correction of the minimum by the change in inflation of the previous year, plus the growth of GDP two years earlier. This rule will become law in 2011.

Even so, in Lula’s second term, the appreciation loses some steam.

“The Dilma government maintains the same valuation policy, but in a lower growth scenario, which translates into lower minimum adjustments,” Duque notes.

Under Temer and Bolsonaro, in a scenario of fiscal restrictions, the minimum valuation policy is abandoned and adjustments are now made exclusively for inflation.

Added to this, in the Bolsonaro government, a sharp surge in food inflation – impacted by the pandemic, crop failures due to climate problems and the war in Ukraine – which further undermined the purchasing power of the minimum wage compared to the basic food basket. .

With the return of appreciation, Duque highlights the importance of the base salary.

“The minimum wage was largely responsible for reducing income inequality in the country between 1995 and 2015,” notes the economist.

“There has also been an important effect in the fight against poverty, above all for the benefits linked to this value”.

According to Dieese, Brazil has 60.3 million people with minimum wage income, with 24.8 million INSS beneficiaries and 18.4 million employees, among other groups.

The minimum also has an impact on workers without a formal contract and on their own, as it serves as a benchmark for the whole economy.

Impact of the readjustment of the minimum on the public finances

Despite these positive effects, the enhancement of the minimum has a cost.

According to government calculations, each R$ 1 increase in the minimum wage impacts R$ 368.5 million a year on the public finances.

Therefore, the R$ 18 increase that takes effect now in May is expected to generate an impact of R$ 4.5 billion on public finances between May and December this year.

For 2024, the government sent the draft Budgetary Guidelines (PLDO) with a minimum wage forecast of R$ 1,389, which only considered the adjustment to inflation.

But, according to Labor Minister Luiz Marinho, the government should present to Congress a bill that resumes the policy of real appreciation that has prevailed in previous PT governments.

If the rule is revived, the minimum would go to BRL 1,429 in 2024, generating an additional BRL 14.7 billion cost to public finances next year.

In addition, the government only increased the value of Bolsa Família until May, adjusted civil service salaries by 9%, and announced an increase in the income tax exemption bracket to R$2,640.

Faced with all this, analysts see with disbelief the promise of the Minister of Finance, Fernando Haddad, to eliminate the primary deficit as early as 2024.

The main outcome is the difference between government revenues and expenditures, and deficit occurs when this outcome is negative.

“The goal of zeroing the deficit next year is not compatible with the current structure of government revenues and expenditures”, believes Vilma Pinto, director of Ifi.

So the government will have to cut spending or increase revenue to balance public finances.

“The government has signaled that this should be on the revenue side [isto é, com maior arrecadação]but the big question is that it cannot be a non-recurring revenue, it must be something that generates a medium-term effect, so that there is an impact on the sustainability of public finances”, explains the economist.

“Because our debt is already at a high level, if we fail to generate an outcome that makes it stable, this affects agents’ expectations and increases fiscal risk. This has consequences for economic activity, with effects on inflation and on the unemployment rate…”

In other words, if the fiscal imbalance persists, the benefit of raising the minimum wage above inflation could be eroded by accelerating prices and lower job creation.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.

![Tomorrow belongs to us: What awaits you in the episodes of 2052 and 2053 on October 15, 2025 [SPOILERS] Tomorrow belongs to us: What awaits you in the episodes of 2052 and 2053 on October 15, 2025 [SPOILERS]](https://fr.web.img6.acsta.net/img/39/95/3995a2d00abbf3c01161818d01a95388.jpg)