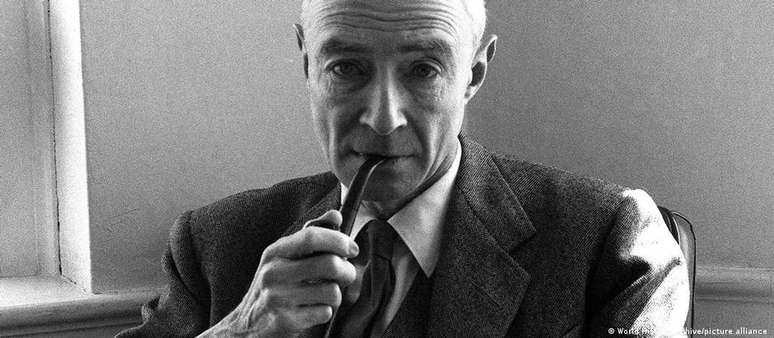

Building the bomb cost almost as much as landing on the moon. Thousands of people worked day and night on the Manhattan Project. The Goal Was to Create the Bomb Before the Nazis No one knows how many times physicist Robert Oppenheimer drove down the highway from Santa Fe to Los Alamos. Under the blue sky you travel between winding hills, you look at the bottom of precipices, wide landscapes are constantly revealed. This is one of the most scenic stretches in New Mexico. Oppenheimer hoped the view would inspire his fellow scientists.

Los Alamos is a paradise and, at the same time, the place where the first weapon of mass extermination in history was developed. In this natural idyll, Oppenheimer headed the Manhattan Project, with which US President Franklin D. Roosevelt intended to win the race against Adolf Hitler’s Germany for the first atomic bomb.

For the military research project, the New York scientist of Jewish descent has assembled a “spectacular collection of brilliant minds, never seen before,” reports Heather McClenahan, director of the local history museum. Among them were Nobel Prize winners in physics Enrico Fermi, Niels Bohr and Hans Bethe.

In all, some 6,000 scientists and their families lived on the project premises, as well as more than 125,000 employees in laboratories and production units spread across the country. However, it was in distant New Mexico that all currents converged, more precisely in the imposing building of the Los Alamos Ranch School, a prestigious elite school, evacuated specifically for this purpose in 1943.

Since the core idea of the project was developed in the Manhattan borough of New York, it received the official title of “Manhattan Engineering District”, but later the designation “Manhattan Project” was established.

It costs almost as much as a trip to the moon

In the wood-panelled main auditorium that served as the dining room and meeting room, William Hudgens, one of Oppenheimer’s staff chemists, recalls nostalgically more than 70 years later: “Everyone knew each other, there was no hierarchy.” During lunch it could happen to find yourself, by chance, sitting next to the “very nice” project manager, whom everyone called “Oppi”.

The team’s average age was 26 years old. Hudgens remembers a lot of partying and drinking. However, at the same time, the atmosphere was very tense and the workload enormous. “We were all very worried that the Germans would beat us to the bomb that would decide the war.”

The Manhattan Project was a top priority for the US government, with virtually unlimited resources. What started in 1940 with a budget of $6,000 grew to $2 billion over five years.

McClenahan believes this was “the most expensive research project since the moon landing”. In addition to its centralizing function, however, Los Alamos had another, decisive purpose, that of a “foundry for the weapons of the project”, underlines the museum director.

His goal was to prepare a nuclear weapon based on all available scientific data on uranium enrichment and chemical purification of plutonium. Because in the Manhattan Project, both the uranium and plutonium bombs were developed in parallel.

unobtrusive memorial

On July 16, 1945, everything was ready for testing the new weapon. The chosen one was the plutonium bomb, which was the more complicated of the two. The uranium bomb remained untested, as there was not enough enriched uranium for a second bomb.

The test area was the White Sands Missile Range, located over 300 kilometers from Los Alamos. At the time, 60 ranchers had to turn over their land to the US military, says public relations consultant Lisa Blevin. He is the tour guide for the gigantic terrain, totaling 8,300 square kilometers, which the US military opens to visitors only once a year.

A 45-minute drive takes the group, mostly physics and chemistry students from Los Alamos, to the site of the explosion. Only a slight depression in the land suggests a crater. Sloppy photos of the explosion hang from the security fences, and a kind of obelisk commemorates the historic moment. Blevin confirms that the radiation level is ten times higher than normal, while noting that this radioactive load is less than what you’re exposed to during a four-hour flight.

German physics student Max comments: “I don’t like atomic weapons.” According to him it would have been better not to build the bomb. On the other hand, it was good that the Cold War was “softened” by the weapon. After all, there has been no war between countries that had “nuclear capabilities”, concludes the 24-year-old.

deep doubts

That day in the summer of 1945, physicist Oppenheimer and General Leslie R. Groves, general manager of the project, watched the test from a safe distance. Eyewitnesses would highlight the beauty radiated by the mushroom cloud and the brightness of the explosion.

Just a month later, the US military dropped bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. Many of the Manhattan Project scientists were surprised to hear the news on the radio. Some had doubted until the last moment that the warheads would work.

At the Los Alamos labs, “the prevailing feeling was one of relief, but there was no big celebration,” recalls the 90-year-old Hudgens. “We had no desire to celebrate something that had killed so many people.”

However, “bombing saved millions of other lives by shortening World War II,” he says, adding that he is sure many of the other participating scientists share this view. For the chemist, this job was “a rare opportunity, and the best thing that could have happened in my life”. After all, that bomb changed the world, Hudgens says.

Robert Oppenheimer’s assessment was different. He now had blood on his hands, he would later tell President Harry S. Truman during a speech at the White House. Deep doubts will accompany the scientist until his death in 1967 at the age of 62.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.

![A more beautiful life in advance: Laura a victim of bad luck?… What awaits you in the week of October 20-24, 2025 [SPOILERS] A more beautiful life in advance: Laura a victim of bad luck?… What awaits you in the week of October 20-24, 2025 [SPOILERS]](https://fr.web.img2.acsta.net/img/6d/6b/6d6b378ffddf3577e6eecf22ca973fa1.jpg)