In the 1950s, large-scale research was conducted on the island to test the contraceptive pill among poor women.

Two women, in a public housing complex in San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico, look on in bewilderment.

One of them, shy, describes some symptoms: “The world disappeared, my vision became blurred. The only thing I said was: ‘Our Lady of Mount Carmel, take care of my children'”.

Then, shaking her head, the other comments: “They were experimenting on us without us knowing.”

The scene is part of the documentary The operation (1982). The women, whose names are not mentioned, described their participation in the first large-scale clinical trial testing the effectiveness of the birth control pill in the 1950s.

In the film they both say they didn’t know they were part of the research.

Like them, hundreds of other Puerto Rican women of humble origins were, without knowing it, patients of the study conducted by two American academics.

The drug, which since its commercialization in 1960 has allowed women to have greater control over their bodies, since they do not depend on men to plan motherhood, was tested in Puerto Rico thanks to a peculiar public policy of overpopulation control promoted by the local government of the island of Puerto Rico and the United States.

In the context of the baby boom during the first half of the 20th century, with many citizens living in extreme poverty, the solution of US-appointed politicians at the time was to encourage Puerto Ricans not to have children.

And its initiatives, explains Ana María García, professor at the University of Puerto Rico and director of The operationthey were specifically designed so that this population reduction would occur among the poorest communities.

“They were aimed at the country’s poorest, racial minority and least educated women,” says Lourdes Inoa, of the Puerto Rican feminist NGO Taller Salud.

“Because they were the ones who least had the opportunity to know the consequences of participating in this type of procedure. Consent, in this context, is highly questionable,” he adds.

With private funding, but also from the state, the island was “a great birth control laboratory,” says García.

And women, adds Inoa, have become “guinea pigs”.

Two scientists and two activists

The origin of the pill, which according to the United Nations is currently used by 150 million women worldwide, occurred far from Puerto Rico, within the walls of the prestigious Harvard University, in Massachusetts, USA.

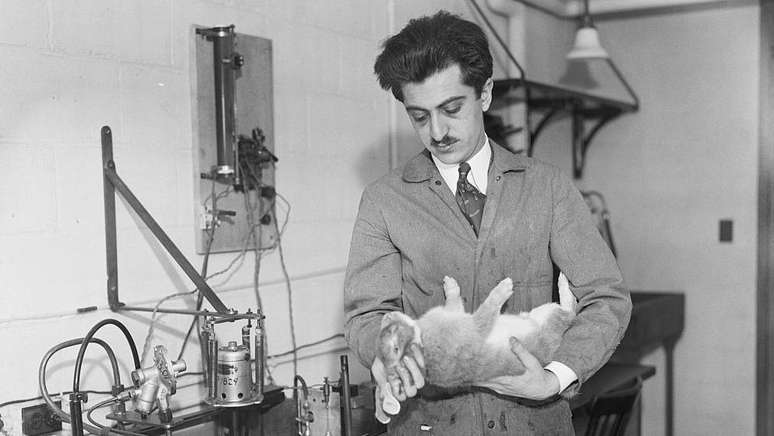

Those who developed the medicine were two renowned professors of the institution: John Rock and Gregory Pincus.

The former was one of the most important fertility experts in North America, says historian Margaret Marsh, a professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey. Rock was paradoxically Catholic and thought couples should have the right to decide when to have children.

Pincus was a biologist who on more than one occasion described overpopulation as “the biggest problem facing developing countries.”

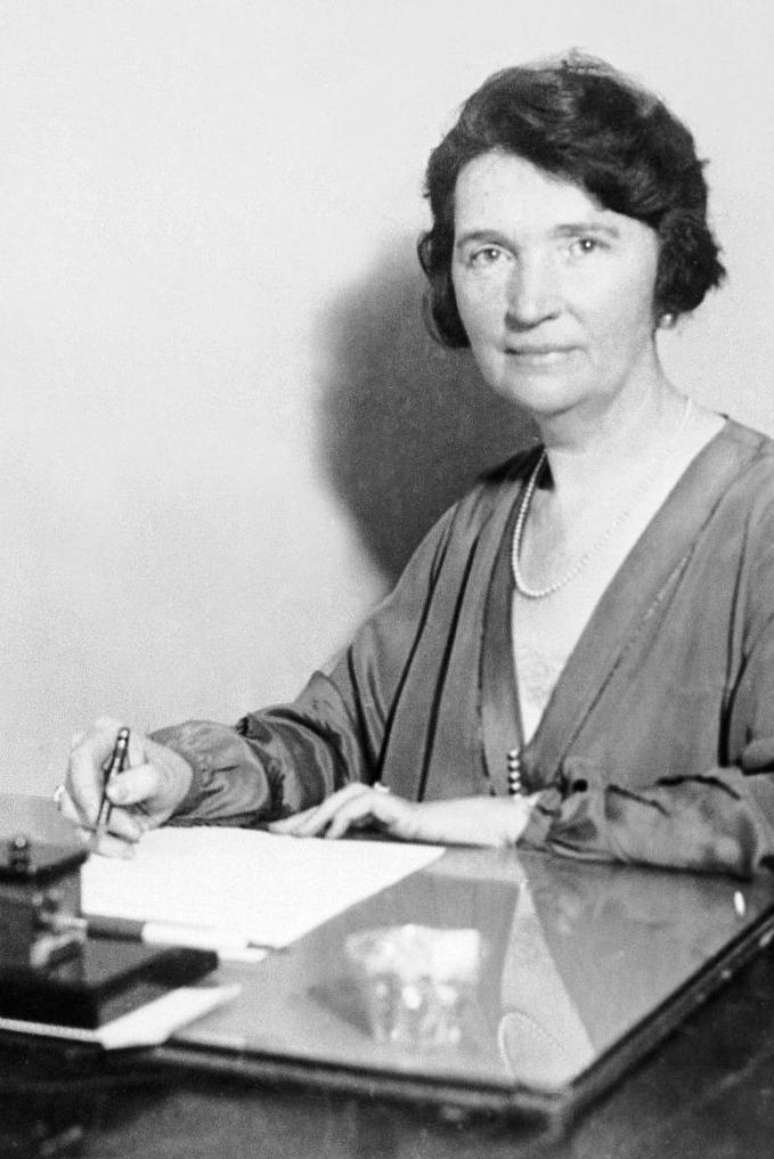

Both were funded and closely supervised by Margaret Sanger, a nurse and health specialist who founded the reproductive health nonprofit Planned Parenthood, and wealthy suffragist leader Katharine McCormick.

They, Inoa says, “sought women to be included in different aspects of society, so that they would have more power.” Control of motherhood was essential to this.

But Sanger famously defended eugenics, the social philosophy that advocates the improvement of the human race through biological selection.

And that’s why he allowed the pill to be tested on poor and vulnerable women.

“The birth control movement, in a sense, was twofold. One was that women should make their own reproductive decisions, and the other was the idea that birth control was good because poor people would fewer children,” adds Marsh.

The first studies

The first birth control pill research in the United States was conducted on rats and other animals.

Then, in a move considered unethical, scientists administered the drug to a small group of patients at a public psychiatric hospital in Massachusetts, says Marsh, who specializes in the history of contraception in the United States.

“The patients’ relatives gave permission to carry out the study, but they themselves, being admitted to a psychiatric hospital, did not consent. Even though it was legal at that time,” he comments.

At this point, Pincus and Rock discovered that the compounds they created had the effect of stopping ovulation. So they looked for a place to do a larger-scale test, so that U.S. regulators could approve the pill.

In Massachusetts, explains Professor García, birth control was illegal. There were also legal limitations for testing on human subjects.

It was then that scientists had to identify an “ideal location”.

The laboratory island

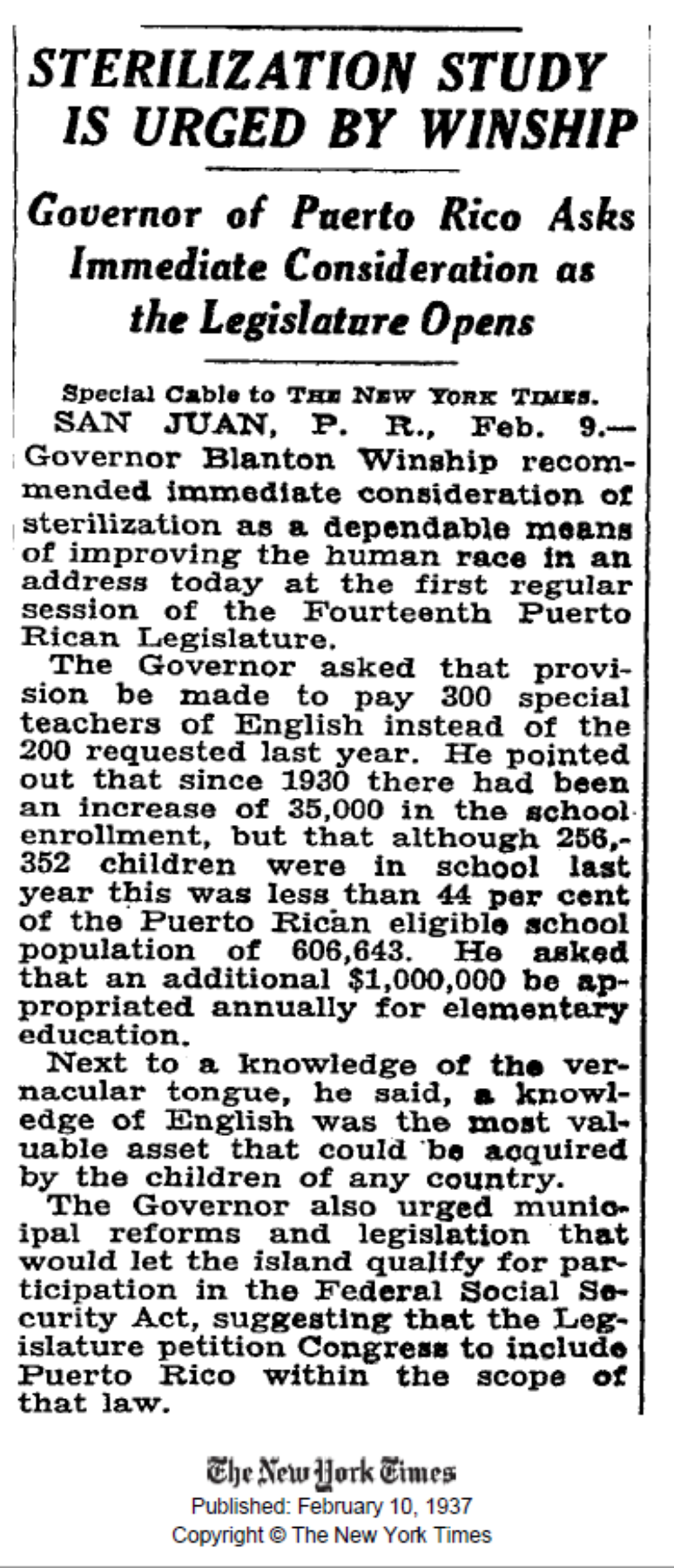

They decided to go to Puerto Rico because sterilization and contraceptive testing in general had been legal there since 1937.

“A law was approved at a historic moment, when in the rest of the planet, including the USA, widespread sterilization was not legal”, underlines García.

The legislation was signed by Governor Blanton C. Winship, a man who also publicly supported eugenics and who – according to a New York Times article – encouraged population control research in Puerto Rico because to him it was the only “reliable” means of improving the human race.”

In the 1950s, when pill researchers arrived on the island, 41 percent of Puerto Rican women of reproductive age had already tried some form of contraception, according to a University of Puerto Rico study.

This was possible thanks to the fact that the legislation allowed the creation of dozens of family clinics throughout the territory, even in the most remote cities, subsidized by the government and with employees who promoted birth control among women.

The network of clinics also attracted the attention of Pincus and Rock, who thought they could use them to develop their project.

The team, however, decided to focus first on a single neighborhood in San Juan, the country’s capital.

The women of Río Piedras

The experience began on the island in 1955 as a project in which medical and nursing students participated. But the study was very complicated and painful, so many did not complete it.

Furthermore, the pill tested in Puerto Rico had a much higher dosage than the current one and caused strong side effects.

“Urinalysis, endometrial biopsies and other tests are needed to determine whether or not they were ovulating. It’s an uncomfortable procedure. If you have students who don’t really need contraceptives, they wouldn’t be willing to continue,” Marsh says.

The drug caused nausea, dizziness, vomiting and headache.

Pincus, however, dismissed these side effects as a “psychosomatic” consequence (when a physical symptom is caused by emotional or psychological problems).

“He believed in the pill so much that he gave it to his family members. His nieces, his daughters, his sons’ friends,” says Marsh, who wrote a biography about Pincus’ colleague Rock.

The team decided to continue the experimentation, but this time in Río Piedras, a northern suburb of Puerto Rico.

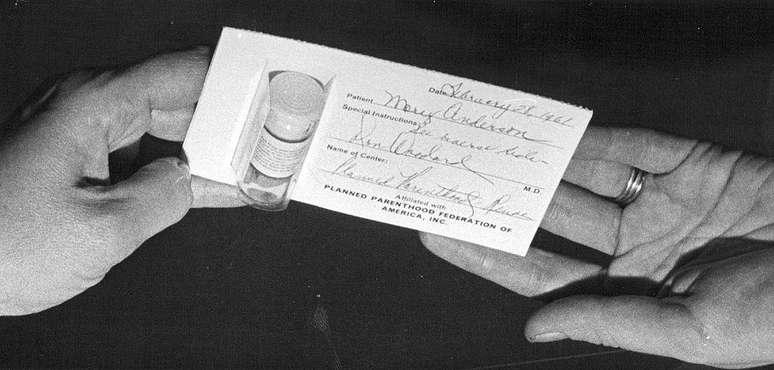

Social workers and medical teams visited women door to door, offering them contraceptive pills and, for some of them, carrying out tests to collect data, without any monetary compensation.

The rejection from various sectors of Puerto Rican society was immediate.

“There were press reports that classified the research as ‘Malthusian,'” says Inoa, of Taller Salud. English economist Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) developed a theory of population growth and food production and believed in the need for birth control to contain the rapid rate of population growth.

“[Houve críticas] even from doctors, even those who were recruiting women, who thought that side effects should be taken seriously and that more testing was needed and not ignored.”

Due to side effects, many of these women, as in previous studies, decided to stop treatment. Others, stricken by poverty, agreed to take the pill as a reversible method of contraception.

According to Marsh, three people died in the clinical trial carried out on the Caribbean island. However, an autopsy was never performed on them, so the exact causes of their deaths are unknown.

The approval

Despite the deaths, given that the pill had the effect of preventing pregnancy, scientists extended the project to other cities in Puerto Rico and, later, to Haiti, Mexico, New York, Seattle and California.

In total, approximately 900 women participated, of which approximately 500 were Puerto Rican.

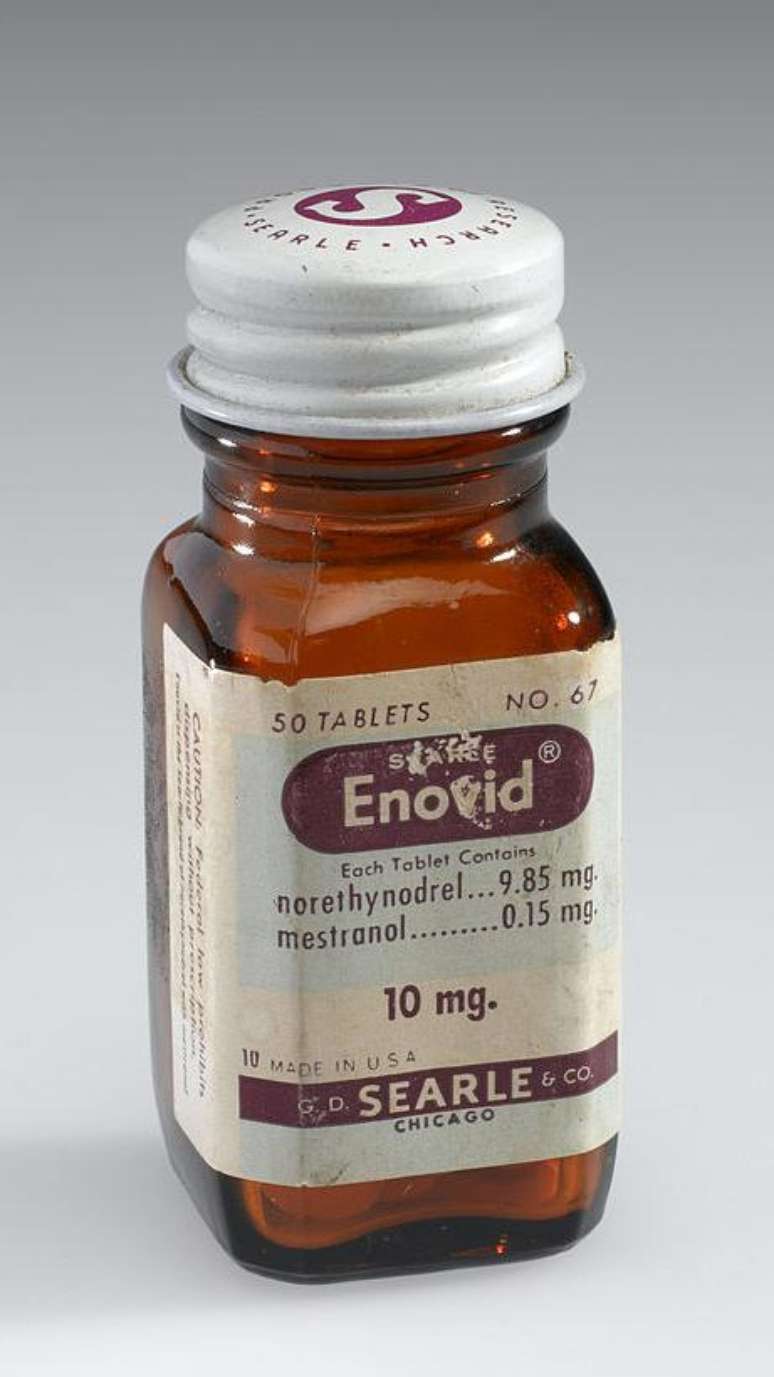

In 1960, the FDA, the US drug regulatory agency, approved Envoid, as the first pill was called, as a method of contraception.

Its expansion was rapid. In just seven years, 13 million women worldwide have used the product.

But after being approved by the FDA, the pill continued to cause serious side effects, including blood clots, which led to lawsuits. On the island, despite lawsuits elsewhere in the United States, studies continued until 1964.

Even today, Inoa explains, there is no “significant” research looking for “another type of contraceptive method that does not have the side effects of the currently existing pill”.

Meanwhile, studies to create an oral contraceptive for men have also not borne fruit, although they began 30 years ago.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.

![Tomorrow Belongs to Us: What’s in store for Wednesday 22 October 2025 Episode 2058 [SPOILERS] Tomorrow Belongs to Us: What’s in store for Wednesday 22 October 2025 Episode 2058 [SPOILERS]](https://fr.web.img6.acsta.net/img/95/64/95643daa3fa690142f3135b300b4ef9d.jpg)