Study shows that these tiny animals use genes “stolen” from bacteria to protect themselves from infections

New research shows that small animals fresh water “steal” recipes from antibiotics In bacteria to protect yourself from infections.

The study was conducted by a team from the University of Oxford, the University of Stirling and the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) and published on Thursday (18) in the scientific journal Nature.

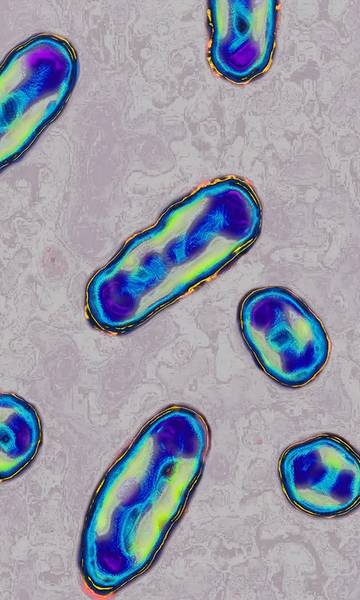

You bdelloid rotifers They are tiny creatures, with a head, mouth, intestines, muscles and nerves, but they are smaller than the width of a strand of hair.

Research has found that when rotifers suffer from infections fungalthey activate a series of genes that they have acquired from bacteria and other microbes. There are genes there that can produce a resistance defense, such as antibiotics and other types of agents antimicrobialsin rotifers.

“When we translate the code of DNA “To see what the stolen genes were doing, we were in for a surprise,” lead author Chris Wilson of the University of Oxford said in a statement. “The key genes were instructions for chemicals we thought animals couldn’t make—they looked like recipes for antibiotics.”

Discover the 5 most dangerous bacteria for your health according to the WHO

In previous research, scientists had discovered that rotifers have the ability to capture DNA from their surroundings for millions of years.

But the new study is the first to show that they have evolved to use these captured genes to protect themselves from disease. No other animal is known to “steal” genes. microbes on a large scale.

“This raises the possibility that rotifers are producing new antimicrobials that may be less toxic to animals, including humans, than those we’ve developed from bacteria and fungi,” said study co-author David Mark Welch, senior scientist and director of the Josephine Bay Paul Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory.

According to the study, the tiny animals copied the DNA that tells microbes how to make antibiotics.

“We saw them use one of these genes against a disease caused by a fungus, and the animals that survived the infection produced 10 times more of the chemical than the ones that died, indicating that this helps suppress the disease,” Wilson explains.

Scientists suggest that understanding this behavior of rotifers could help in the search for drugs to treat human infections caused by bacteria or fungi, as the development of new drugs can be potentially problematic.

The study highlights that many chemical antibiotics produced by bacteria and fungi are poisonous or cause side effects in animals, so only some of them can be transformed into treatments for humans.

But by understanding how rotifers produce similar chemicals in their own cells, there is an opportunity to pave the way for new drugs that are safe for animals and people.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.