Adored by some, rejected by others, daylight saving time was only adopted at the insistence of a British designer.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) is expected to decide this week on a possible return to daylight saving time.

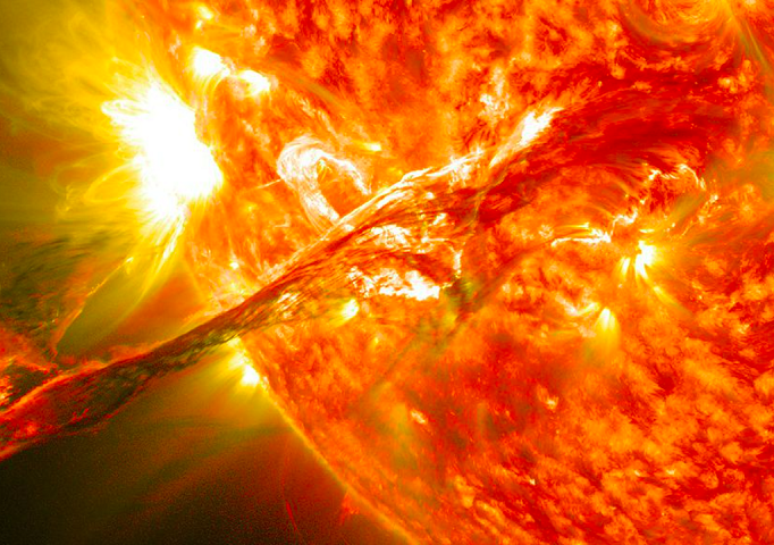

The measure was called into question by the government due to the record drought that is devastating the country and the approaching period of the most intense heat.

Drought reduces the level of hydroelectric reservoirs, the main source of electricity in Brazil. Heat increases energy consumption, due to the more frequent use of appliances such as air conditioning.

Daylight saving time was abolished in the country in 2019, the first year of Jair Bolsonaro’s (PL) government. At the time, Bolsonaro’s team argued that the energy savings resulting from this practice were low and did not justify the adoption of the measure.

The National Electricity Agency (Aneel) and the National System Operator (ONS) will present a study on summer time in the current circumstances in the coming days. The final decision will be up to Lula.

But who invented daylight saving time? And when was it first adopted?

An Englishman with an idea

Once upon a time there was a middle-class builder who lived in the suburb of Chislehurst, south-east London.

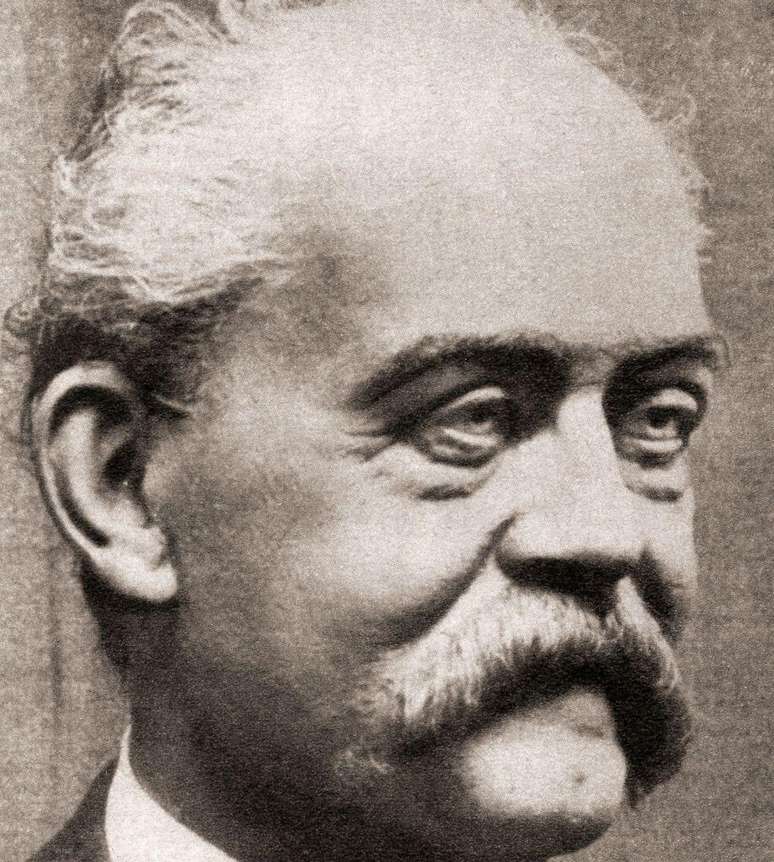

His name was William Willett (1856-1915). And if it weren’t for him, the British – and a quarter of the planet, including Brazil until 2019 – might never have adopted daylight saving time.

Willett loved the outdoors. One summer morning in 1905 he was riding a horse when he noticed that many of the curtains were closed, preventing sunlight from entering the houses.

Then he had an idea: why not move the clocks forward before the start of summer?

Willett was not the first to come up with this measure. Ancient civilizations already shortened and lengthened the days, depending on the season. In Ancient Rome, for example, an hour could last 44 minutes in winter and 75 in summer.

In 1895, New Zealand entomologist George Hunter proposed a two-hour change, but his idea was ridiculed.

And, six years later, in 1901, British King Edward VII (1841-1910) turned the clocks back 30 minutes at Sandringham, UK (where one of the royal residences is located), so he could devote more time to hunting.

But it was up to Willett to make sure that daylight saving time was finally adopted.

In 1907 he published an independent pamphlet entitled Waste of daylight (“Waste of Daylight”, in free translation), arguing that in the UK the clocks be moved forward four times in April, by 20 minutes each time, to return to normal time in the same way in September.

Willett argued that in addition to increasing recreational opportunities, the measure would reduce lighting expenses.

Its supporters included prominent politicians, including two future British Prime Ministers: David Lloyd George (1863-1945) and a young man called Winston Churchill (1874-1965), then president of the Chamber of Commerce.

Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) also expressed his support during the discussions on the DST Act, although he disapproved of Willett’s cumbersome partial adjustments.

“A single one-hour change would be a round number and cause less confusion,” Conan Doyle told the committee considering the proposal.

Among its opponents was the then Prime Minister Herbert Asquith (1852-1928). The bill was defeated in 1909 by a small margin, and subsequent proposals suffered the same fate.

Playing with the clocks, it seemed, was too radical a change for the time, even under a reformist Liberal government. But Willett was tireless and continued to ardently defend DST in the UK, continental Europe and the Americas until his death from influenza in 1915.

Just a year after Willett’s death, a revised version of his proposal was finally accepted, prompted by the most extenuating circumstance of all: war.

Two years after the outbreak of the First World War, the United Kingdom was suffering from a severe shortage of coal, the main source of energy for the country’s industries and homes.

“In addition to increased demand to supply the navy, railways and armaments industry, the UK needed to supply coal to the Allies, whose mines were being taken over by Germany, not to mention the thousands of miners who volunteered for the war,” says history professor David Stevenson, of the London School of Economics.

Willett’s ideas promised relief, with less demand for coal-fired lighting.

Germany passed the Summer Time Act on April 30, 1916, and the United Kingdom followed suit soon after, on May 17. This type of imitation was common, according to Stevenson.

“The UK was taking [ideias] borrowed from Germany a long time ago,” explains the professor. “Many British politicians and intellectuals were fascinated by the country, as an example of superior national efficiency.”

Under the new law, clocks would be moved forward one hour from Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) during British Summer Time.

Several other European countries quickly followed the measure, as well as the United States (which coined the famous expression “advance in the spring, retreat in the autumn”), Uruguay, New Zealand, Chile and Cuba.

Doubling the bet

The United Kingdom has undergone occasional changes to summer time throughout the 20th century.

During World War II, the country set its clocks two hours ahead of GMT. It was called Double Summer Time, to further reduce costs in the industry.

Between 1968 and 1971, the country experimented with British Standard Time, moving the clocks forward one hour throughout the year. But the test was marred by children having to wear fluorescent armbands on dark winter mornings, and the measure proved deeply unpopular.

Since then, several proposals in Parliament have challenged daylight saving time – and not just in the UK. Similar measures are constantly being created, modified, challenged or discarded in various parts of the world.

In Brazil, daylight saving time was first adopted in 1931, but its practice was irregular. From 1985 onwards, clocks began to advance one hour each year, until the cancellation of daylight saving time in the country in 2019.

Why is daylight saving time such a controversial topic? Basically, the pros have never convincingly outweighed the cons. For every undeniable argument in favor of daylight saving time, there is always a clear counterfactor.

In short, daylight saving time benefits above all trade, sport and tourism, but harms agriculture and workers and students who wake up too early in the morning.

No one knows this debate better than David Prerau, author of the book Seize the light of day (“Enjoy the light of day”, in the free translation).

“In general, daylight saving time is believed to reduce energy consumption, traffic accidents and outdoor crime, as well as ensuring a better quality of life,” he says.

“But on the downside, there are dark mornings – a problem especially for schoolchildren and farmers – and the effect of the dysrhythmia on sleep rhythms.”

A recent Finnish medical study has even linked daylight saving time to strokes, blaming it on the disruption of the body’s circadian rhythms.

Clock changes are often also a political tool.

In celebration of the 70th anniversary of the independence of the Korean Peninsula in August 2015, North Korea turned back its clocks by 30 minutes, returning to the time zone used before the Japanese occupation.

The state news agency said the aim was to “eradicate the legacy of Japan’s colonial period.” The measure was scrapped in 2018 to eliminate the time difference it had created with South Korea.

The Legacy

About a quarter of the world’s 7.4 billion people observe daylight saving time. Prerau has no doubts about who deserves credit for adopting this measure.

“The passage of the laws establishing daylight saving time stems directly from the efforts of William Willett,” he says.

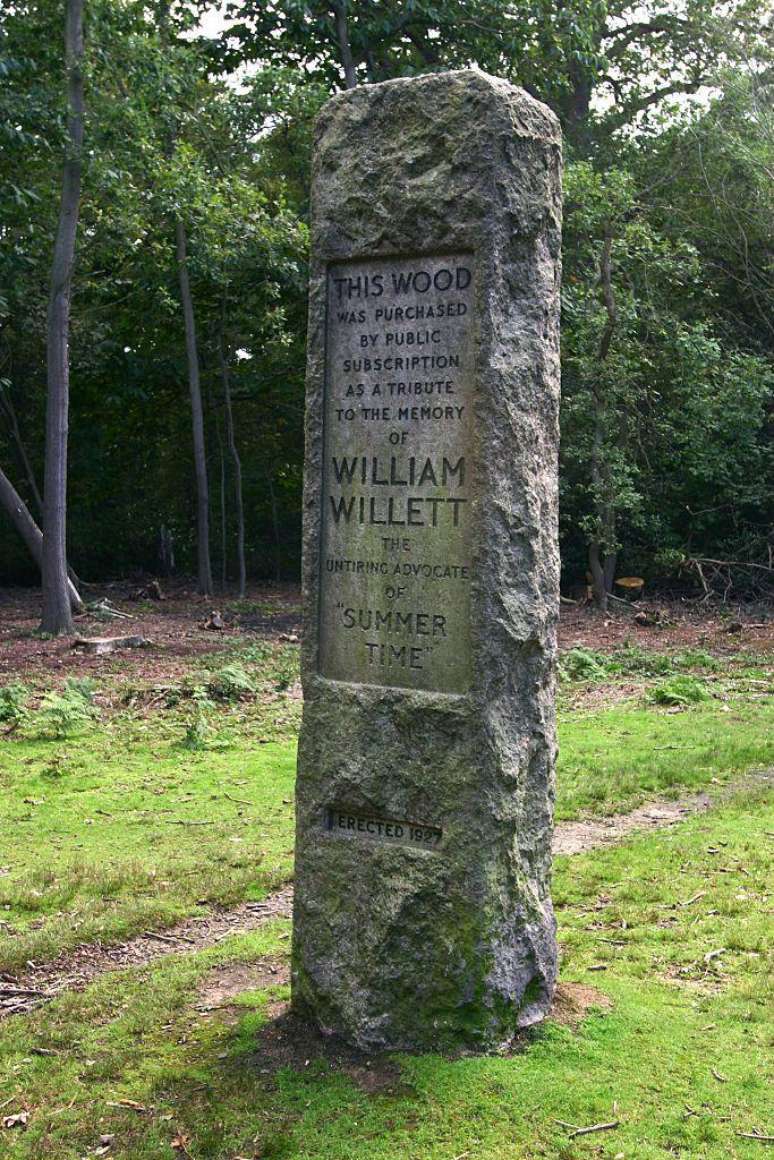

When we look at Willett’s simple grave outside the quiet St Nicholas Church in Chislehurst, it is hard to believe that he continues to maintain his global influence so long after his death.

In the suburbs, Willett’s legacy is recorded on a plaque at his former home, in the pub called The Daylight Inn, in streets named after him and in letters, papers and photographs on display in the Chislehurst Society community hall.

But doesn’t it deserve greater recognition?

“Absolutely,” replies Joanna Friel of the Chislehurst Society. “Willett defended himself [o horário de verão] so passionately and simply refused to give up. He was an extraordinary and ultimately very important figure.”

Chris Martin, lead singer of the British rock band Coldplay, is one of William Willett’s great-grandsons.

The opening verse of your song Clocks (“Clocks”) includes a possible reference to daylight saving time: “the lights are going out and I can’t be saved.”

In 2016, the band performed at the Glastonbury Festival in the UK. They took the stage at around 10:15pm, roughly the same time as sunset, thanks to British Summer Time and William Willett, the man who changed the clocks.

*As written by BBC News Brasil for the Brazilian context in 2024.

This report was originally published on November 25, 2023.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.