Research shows that the slowing of the Atlantic Southern Circulation (AMOC) will have consequences for climate and ecosystems around the world.

A vast network of marine currents nicknamed “the great global conveyor belt” (great global ocean conveyor belt in the original English” is slowing down. And that’s a problem because this vital system redistributes heat around the world, affecting both temperatures and precipitation.

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (South Atlantic overturning circulationor AMOC, in English) conveys heat from south to north across the Atlantic Ocean and is fundamental for the stability of the climate and marine ecosystems. It is weaker today than at any time in the last 1,000 years, and global warming may be to blame. But climate models have struggled to reproduce the changes observed so far – until now.

Our models suggest that the recent weakening of ocean circulation can be explained if we take into account meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet and Canadian glaciers in the Arctic.

Our results show that the Atlantic overturning circulation will likely become a third weaker than 70 years ago with 2°C of global warming. This would bring major changes to climate and ecosystems, including faster warming in the Southern Hemisphere, harsher winters in Europe and weakening of tropical monsoons in the Northern Hemisphere. Our simulations also show that these changes are likely to occur much sooner than previously suspected.

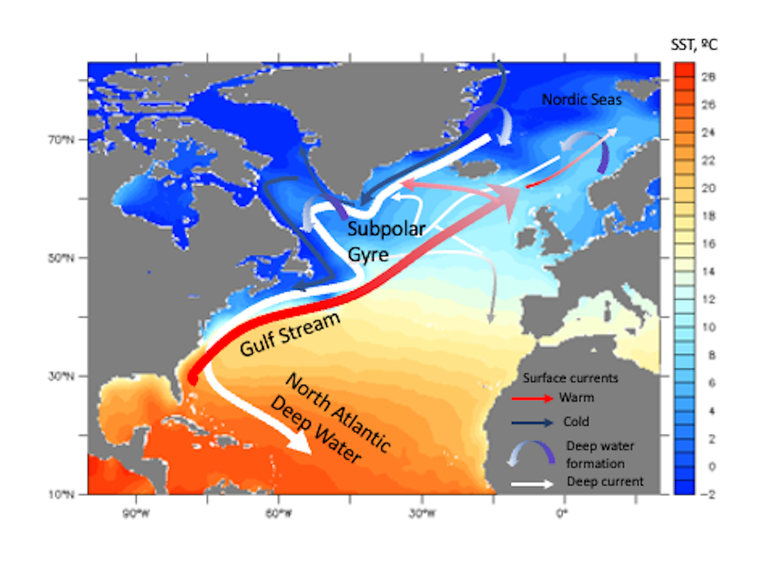

The Atlantic Southern Circulation (AMOC): what is it and why is it so important? (National Oceanographic Center)

Changes in the Atlantic circulation

The Atlantic Southern Circulation has been monitored continuously since 2004. But a long-term view is needed to evaluate possible changes and their causes.

There are several ways to find out what was happening before the measurements began. One technique is based on sediment analysis. These estimates suggest that the current Atlantic meridional circulation is the weakest in the past millennium and has become weaker by about 20% since the mid-20th century.

Evidence suggests that the Earth has already warmed by 1.5°C since the industrial revolution.

In recent decades, the rate of warming has been almost four times faster in the Arctic.

Meltwater weakens ocean circulation

High temperatures are melting Arctic sea ice, glaciers and the Greenland Ice Sheet.

Since 2002, Greenland has lost 5.9 trillion tons (gigatons) of ice. To put this into perspective, imagine if the entire Australian state of New South Wales (a little smaller than Mato Grosso) was covered in a layer of ice 8 meters thick.

This fresh melt water that flows into the subarctic ocean is lighter than salty seawater. Therefore, less water sinks into the depths of the ocean. This reduces the southward flow of deep, cold water from the North Atlantic. It also weakens the Gulf Stream, which is the primary path for warm waters to flow back northward to the surface.

The Gulf Stream is what gives Britain mild winters compared to other places the same distance from the North Pole, such as Saint-Pierre and Miquelon in Canada.

Our new research shows that meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet and Arctic glaciers in Canada is the missing piece of the climate puzzle.

When we take this into account in simulations, using an Earth system model and a high-resolution ocean model, the slowing of ocean circulation reflects reality.

Our research confirms that the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation has slowed since the mid-20th century. It also offers a glimpse into the future.

As they move north, the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Current cool, losing heat to the atmosphere. The waters then become dense enough to sink and form the deep waters of the North Atlantic, which travel southward in depth and feed other ocean basins.

Edited by Nature Reviews Earth and Environment (2020)

Connectivity in the Atlantic Ocean

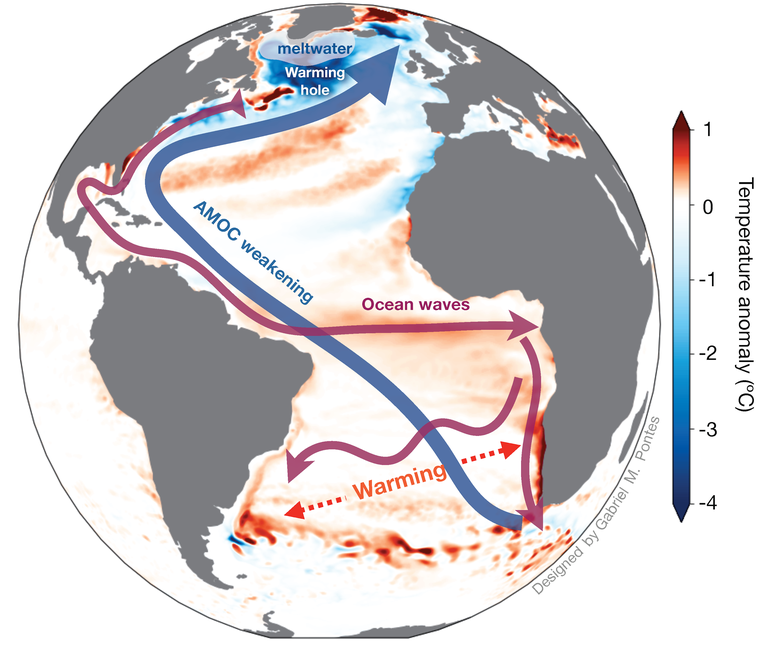

Our new research also shows that the North Atlantic and South Atlantic oceans are more connected than previously thought.

The weakening of the Atlantic Southern Circulation in recent decades has obscured the effect of global warming on areas of the North Atlantic, leading to what has been called a “warming hole.”

When ocean circulation is strong, a large heat transfer occurs towards the North Atlantic. But the weakening of ocean circulation means that the ocean surface south of Greenland has warmed much less than the rest.

Reduced heat and salt transfer in the North Atlantic has caused heat and salt to build up in the South Atlantic. As a result, temperatures and salinity in the South Atlantic have increased more rapidly.

Our simulations show that changes in the far North Atlantic will be felt in the South Atlantic Ocean in less than two decades. This provides new observational evidence of the slowing of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation over the last century.

The addition of meltwater in the North Atlantic leads to localized cooling in the subpolar North Atlantic and warming in the South Atlantic.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-024-01568-1

What does the future hold for us?

The latest climate projections suggest that the Atlantic overturning circulation will weaken by about 30% by 2060. But these estimates do not take into account meltwater flowing into the subarctic ocean.

The Greenland ice sheet will continue to melt over the next century, resulting in a possible global sea level rise of about 10 cm. If this additional meltwater were included in climate projections, the overturning circulation would weaken more rapidly. It could be 30% weaker by 2040, which is 20 years earlier than initially expected.

Such a rapid decrease in overturning circulation will affect climate and ecosystems in the coming decades. Expect harsher winters in Europe and drier conditions in the northern tropics. The Southern Hemisphere, including Australia and southern South America, may experience hotter and wetter summers.

Our climate has changed dramatically over the last 20 years. Faster melting of the ice sheets will further accelerate the disruption of the Earth’s climate system.

This means we have even less time to stabilize the climate. Therefore, it is imperative that humanity takes action to reduce carbon emissions as quickly as possible.

Laurie Menviel receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Gabriel Pontes receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.