The decision of the National Council of Justice grants 30 days to notary offices to make the corrections. The families celebrate, but underline that many requests have not yet been satisfied

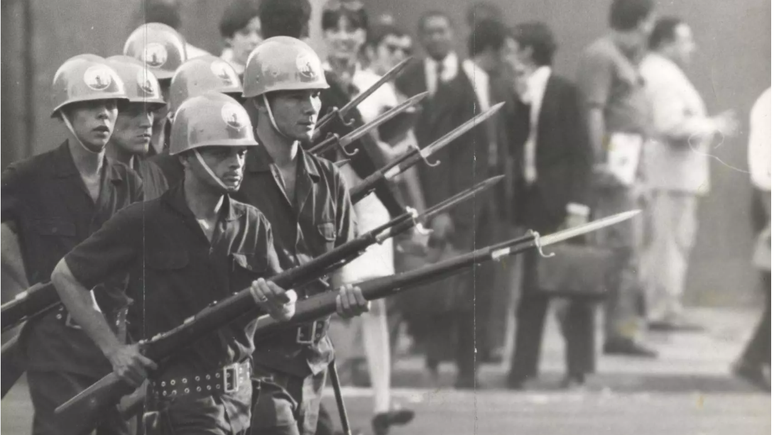

Cause of death: “Unnatural, violent, caused by the Brazilian State in the context of the systematic persecution of the population identified as political dissidents of the dictatorial regime established in 1964.”

More than 400 death certificates of Brazilians who died and disappeared during the military dictatorship will thus be registered.

These are documents that, until now, had an “unknown” cause of death.

Or register “under Law 9.140,” the Law on Political Disappearances, which recognized as dead people who disappeared due to participation or allegations of participation in political activities during the dictatorship.

The changes fulfill one of 29 recommendations in the National Truth Commission’s final report. Established in 2011, the Commission had the role of investigating human rights violations that occurred during the dictatorship. His work continued until the report was delivered in 2014.

The decision of the National Council of Justice (CNJ) will give the civil registry offices 30 days to make the corrections, starting from the notification. Due to the pause in the judicial system, this period has not yet started to run.

The rectification of the death certificates of people killed and disappeared during the dictatorship is something that the families of the victims have been waiting for for a long time.

In the movie I’m still here, the scene in which Eunice Paiva, played by Fernanda Torres, receives the certificate from her husband, Deputy Rubens Paiva, who disappeared at the hands of the military, brought the reality of these families to the cinema.

Rubens Paiva disappeared in 1971, but it was only in 1996 that Eunice obtained a document certifying his death, through the Law on the Dead and Missing, enacted the previous year and which created the Special Commission on the Dead and Missing.

The Commission coordinated the search for and recognition of the bones of possible dead and missing people during the dictatorship and the issuing of death certificates, even for those who were never found, as in the case of Rubens Paiva.

Another emblematic case was that of the family of journalist Vladimir Herzog, who managed, in 2012, to rectify the document which, until then, indicated suicide as the cause of his death.

Six years later, journalist and lawyer Lygia Jobim, daughter of diplomat José Pinheiro Jobim, also received a new death certificate for her father, which stated that the Brazilian state was responsible for his death.

“I remember that day well. I was very excited. I took the document, I looked around on the street. I went into the supermarket, ordered a coffee and stayed there,” Lygia tells BBC News Brasil.

“It’s a very big emotion and, at the same time, strange, because no one is happy when they receive a death certificate.”

When he was kidnapped and killed in 1979, Jobim was writing a book that promised to reveal a corruption scheme involving the Itaipu hydroelectric power plant.

He was found hanging by the neck in a staged scene, just like Herzog, as the courts recognized years later. Even so, his certificate listed the cause of death as “undefined.”

In 2019, in the first year of his government, former president Jair Bolsonaro changed the composition of the Special Commission on Political Deaths and Disappearances, changing four of the seven members, and the processes for rectifying death certificates stalled.

Then, 15 days before the end of his mandate, Bolsonaro abolished the commission once and for all, completely paralyzing the processes.

Human rights activist Maria do Amparo Araújo was caught in the middle of the street.

He asked for the rectification of the documents of his brother, Luiz Almeida Araújo, with whom he fought in the National Liberation Action (ALN), and his partner, Luiz José da Cunha, both of whom died as a result of the repression. But he only managed to rectify his brother’s certificate.

“My partner’s request was rejected,” says she, founder of the NGO Tortura Nunca Mais.

“I appealed and the request was rejected again. This means that there was no standardized procedure [para realizar as retificações] what should it be like now? [com essa resolução do CNJ].”

For her, the news of the rectification of all death certificates is a formalization of the state’s responsibility for political deaths during the dictatorship. But it’s not enough.

“People keep disappearing because they are killed by Military Police.”

Demilitarizing the state police is another of the 29 recommendations in the National Truth Commission report.

Even though the document was presented ten years ago, a survey carried out before the CNJ decision by the Vladimir Herzog Institute showed that a very small part of the recommendations have so far been met.

Of the 29 bills, only two have been fully implemented.

The first was the introduction of the custody hearing, in 2015. This mechanism guarantees that anyone accused of a crime, arrested red-handed, has the right to be heard by a judge, within 24 hours of arrest, so that any possible illegitimacy of the crime is arrested.

The other recommendation that was accepted, in 2021, was the repeal of the National Security Act. Created during the military dictatorship, the law provided for, among other things, a sentence of up to four years in prison for “publicly propagating violent or illegal processes aimed at altering the political or social order”, or for “inciting the subversion of the ‘political or social order’. order or animosity between the Armed Forces or between them and social classes or civil institutions”.

Opening files

Financial specialist Marta Costa, niece of guerrilla fighter Helenira de Souza Resende Nazareth, says emotionally that the rectification of her aunt’s death certificate is a very symbolic step.

“It’s very significant. My mother has been trying for years to get this rectified,” he says. “Today he is 84 years old. This result is a return to this struggle of many years.”

Helenira, whose code name was Fátima, was part of the Guerrilha do Araguaia, a resistance movement to the dictatorship in the Amazon region, when she disappeared.

His body was never found and the family was never able to hold a funeral ceremony.

“We managed to bring the bones from Araguaia to UnB [Universidade de Brasília]but they have been there for years”, says Marta. “There is this anxiety to know if my aunt is there and if we can continue, carry out the burial”.

In July 2024, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva re-established the Special Commission on Political Deaths and Disappearances. One of the first acts of this recovery was the delivery of the request for rectification of the death certificates to the CNJ.

The families recognize this step, but reiterate that the road is still long.

“My mother is 77 years old and until today she has not been able to cry and bury my grandfather,” said Leo Alves, a musician and member of the Brazilian Coalition for Memory, Truth and Justice, an organization that defends democracy, memory and repair. for human rights violations.

Leo is the nephew of the politician Mario Alves, one of the founders of the extinct Brazilian Revolutionary Communist Party (PCBR), who died during the dictatorship.

“This decision is a victory, but that’s not all. It will not include, for example, the burial site. That’s why our work doesn’t end there.”

Lygia Jobim lacks the same information. Even though his father’s death certificate has already been corrected, he demands explanations.

“I wanted an explanation. The cause of death remains unknown. We know it was repression, but the rest of the story escapes me,” says Licia.

“This story doesn’t end here. What did my father die of? Who killed my father?”

Leo Alves also believes that rectification of the documents does not put an end to the whole story.

“Something happened in the field of Memory, but nothing happened in Justice. The condemnation of the agents of repression never existed”, says Leo.

Like all the families of the dead and missing that BBC News Brasil spoke to, the musician was categorical.

“We want the archives to be open,” he said, referring to documents from the dictatorship that have never been made public.

“This story must be told”

Opening the files is another of the recommendations contained in the National Truth Commission report.

According to a document from the Vladimir Herzog Institute, this resolution not only failed to advance, but also withdrew due to the National Truth Commission’s “notorious difficulty in accessing the archives of military bodies”.

In 2004, then-president Lula announced the opening of the archives and a 30-year period, renewable for another 30, for the company to have access to the military regime’s top secret documents.

20 years after the decree, the documents have still not been made public.

“All that the National Truth Commission gave us were documents that we already had,” says Marta Costa.

“This story needs to be told so something like this doesn’t happen again.”

Even the public official Lorena Moroni Girão Barroso, sister of Jana Moroni Barroso, a guerrilla fighter from Araguaia considered politically missing, is asking for access to military documents.

“The rectified death certificate, even if it has the effect of logical reasoning, since now the state takes responsibility for the deaths, the main thing, which is the circumstances in which these deaths occurred, the certificate will not bring,” he says Lorraine.

“This will only happen with the opening of the files.”

Lorena recalls that each step up to this point has been tiring and painful, but with little progress.

“When we filed a lawsuit against the Union to know the location of the bodies, they even denied the existence of the Araguaia guerrillas,” he says.

“Now, in addition to the recognition that there was guerrilla warfare, there is also the recognition that she was one of the victims of the dictatorship.”

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.