A powerful speech by a man – who decades later would be revealed to be John Fryer – spurred the campaign to make homosexuality no longer considered a disorder.

“They could be anywhere,” a police officer filmed by WTVJ in South Florida warned a group of students in 1966.

The agent spoke of the “threat” posed by homosexuals, unaware that the real danger lies in deep-rooted and generalized prejudices.

“It could be police officers, school principals. And if we catch you with a gay man, your parents will be the first to know.”

Being gay was, at the time, illegal in the United States.

By 1962, all 50 U.S. states had criminalized same-sex sex, and it would take until 2003 for all remaining laws to be repealed, paving the way for one of the broadest recognitions of LGBT rights in the world.

But the problem went beyond criminalization.

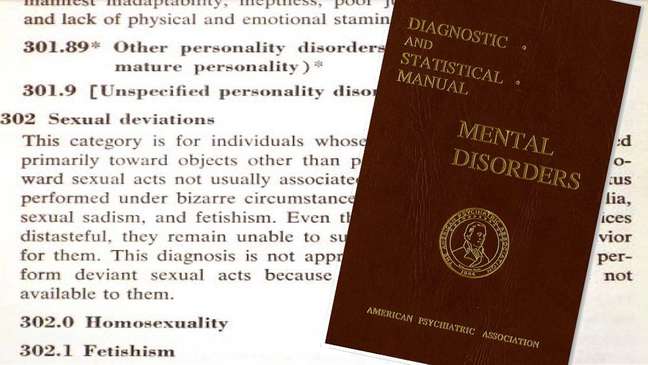

A decade before the criminalization, homosexuality had been included in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (called the DSM, the “bible” of psychiatry and the book of all mental health diagnoses).

This meant that the American Psychiatric Association (APA), a highly influential part of the American medical establishment, had defined homosexuality as a disorder – more specifically, a “psychopathic personality disorder”.

Because of this 1952 classification, anyone outside the bounds of heterosexuality could be institutionalized against their will or even subjected to “cures” such as chemical castrations, electroconvulsive therapies, and lobotomies.

It also had a profound effect not only on how LGBT people were viewed by society, but also on their self-image.

And it made the environment even more hostile.

This “scientific support” of psychiatry for prejudice has translated into various discriminatory practices, from denying homosexuals the right to work, citizenship and custody of children, to exclusion from the clergy, the military and marriage.

The options for the LGBT community were to hide or suffer the consequences. Some have risked the second option.

Curb the madness

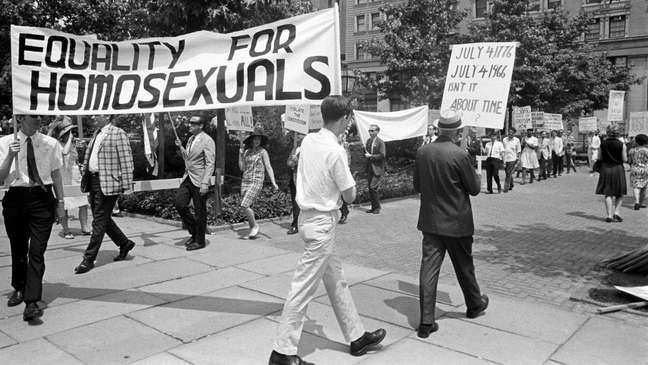

The DSM classification was first criticized in the 1960s by a group of activists led by LGBT rights pioneer Frank Kameny, a Harvard-trained astronomer who had been expelled from the military for being gay.

This group has waged a long campaign calling for homosexuality to be removed from the textbook.

It’s just that the APA’s claim that being gay is a mental disorder hasn’t been backed up by any scientific evidence, which has played into activists’ favor, particularly as the diagnosis began to bother a new generation of psychiatrists.

In 1971, after the group attended an APA annual meeting, they were authorized to organize a panel discussion on homosexuality for the following year’s convention.

The plan was to bring Kameny and Barbara Gittings, who would be known as a pioneer of lesbian liberation, to the judging panel.

But activists thought that the ideal would be to have the speech of someone who is both: a psychiatrist and a homosexual.

There was an underground group calling themselves Gay-PA (a pun on the English pronunciation of APA). Activists wrote to members of the group, all of whom denied taking part in the panel. As much as they agreed with the lawsuit, remaining anonymous would result in, among other things, severe professional penalties.

But lo and behold, one of these psychiatrists changed his mind, and on the second day of the APA meeting, in 1972, something absurd and perhaps even comical, but extraordinary nonetheless, happened.

yes

The conference room of the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas filled with psychiatrists attracted by the controversial theme of an event entitled “Psychiatry: friend or foe of homosexuals? A dialogue”.

Facing the spectators were speakers Gittings, Kameny and psychiatrist Kent Robinson.

At the last moment, a grotesque-looking man emerged from one of the side curtains and stopped in front of the room.

He wore a huge tuxedo, a wig with loose and messy locks, and his face was hidden by a rubber mask of Nixon, then president of the USA.

But if her appearance was striking, it was her words, spoken into a microphone that distorted her voice, that marked the moment the most.

“I’m gay,” he declared. “And psychiatrist.”

‘Live our humanity’

“Like most of you in this room, I’m a member of the APA and I’m proud of it,” said the man, introduced as “Dr. Henry Anonymous.”

He noted that he was not the only gay psychiatrist, and that several colleagues felt it was time for someone of the flesh to stand up “before our organization and ask to be heard and understood, to the extent possible.”

He spoke about the secret world of gay psychiatrists: how they didn’t officially exist and how they lived in hiding, hiding every trace of their private life from the knowledge of their colleagues, fearful of what they would have to lose.

“But we run an even greater risk of not fully living our humanity,” he added.

“That is the greatest loss, our honest humanity, and that loss causes everyone around us to lose even a little bit of their humanity. Because if they were truly comfortable with their homosexuality, they might as well be with ours.” .”

The doctor. Anonymous concluded his speech with a standing ovation.

One of the cheers came from the administrator of Friends Hospital, who however would later fire the man behind the mask – John Ercel Fryer, as it would be revealed twenty years later – stating:

“If you were gay but not flamboyant, we wouldn’t fire you. If you were flamboyant but not gay, neither. But since you’re gay and flamboyant, we can’t keep you,” Fryer himself told the Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy in 2002.

Resignation

It wasn’t the first time this had happened to Fryer. Though he’d been an exemplary academic artist since his school days—he’d entered college at 15 and entered medical school at 19—he was subjected to prejudice when a supervisor discovered he was gay.

In 1964, when he was already living on the (more tolerant) West Coast of the United States and doing his medical residency at the University of Pennsylvania, he ended up telling a friend that he was homosexual. The information eventually reached the university administration, and that’s when the ultimatum arrived: either Fryer resign or he would be fired.

Outside of university, he found work at a state mental hospital to supplement his residency.

Despite all of this, coming out wasn’t appealing to Fryer, so he kept his homosexuality a secret even after the famous outburst.

It wasn’t until 22 years later, in a speech to the APA in 1994, that Fryer stood before the APA and confirmed that he was “Doctor Anonymous.”

But even before that, his words were instrumental in driving a change of opinion within the APA, facilitating the elimination of homosexuality from the DSM.

Gradually, the activists’ persistence paid off, and in 1973, the APA freed homosexuals — in the United States and other places where the DSM is held as a benchmark for mental health — from the stigma of ” I disturb”.

Or, as a representative of the Chicago Gay Crusader put it, “20 million gays have been healed!”

In that trial, the APA stated that the association “supports and urges the enactment of civil rights laws at the local, state and federal levels that give homosexual citizens the same protections afforded to others.” Thus began the long (and still ongoing) process of eliminating the discriminatory and oppressive practices that the diagnosis had endorsed.

It would be decades before gay rights historians fully recognized the relevance of Fryer’s words in that Dallas conference room in 1972.

“I did this isolated act, which changed my life, which helped change the culture of my profession, and disappeared,” Fryer later said.

Today, some compare the importance of this “isolated act” to the Stonewall Riot, which took place in New York in 1969 and which catalyzed the modern LGBT rights movement in the USA.

Fryer died in 2003. This year marks the 50th anniversary of Dr. Fryer’s speech. Anonymous, May 2 has been declared John Fryer Day.

The APA has also begun awarding the “Fryer Award” to individuals who help improve the health of sexual minorities.

– This text was published in https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-63770001

🇧🇷The best content in your email for free. Choose your favorite Terra newsletter. Click here!

Source: Terra

Camila Luna is a writer at Gossipify, where she covers the latest movies and television series. With a passion for all things entertainment, Camila brings her unique perspective to her writing and offers readers an inside look at the industry. Camila is a graduate from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) with a degree in English and is also a avid movie watcher.