According to experts, Italian wineries “switched” from quantity to quality after a crisis that killed 20 people in 1986.

Hundreds of people hospitalized and more than 20 dead: this was the result of a scandal that shook the reputation of Italian wine – and that changed winemaking in Italy forever.

The year was 1986 and the country was consolidating itself as one of the largest wine producers in the world. With thousands of hectares of vineyards and a favorable climate, annual production exceeded 70 million hectoliters (1 hectoliter is equivalent to 100 litres).

The scenario, however, was one of excessive inventories and strong internal competition, which put downward pressure on prices. Many small producers and traders, especially in northern Italy, were looking for ways to increase the alcohol content of cheap wines without increasing costs, which opened the door to illegal adulteration practices.

In March 1986 the first cases of poisoning were recorded in the province of Asti, a Piedmont region known for its viticulture. Two people died and several were hospitalized after consuming table wine sold locally.

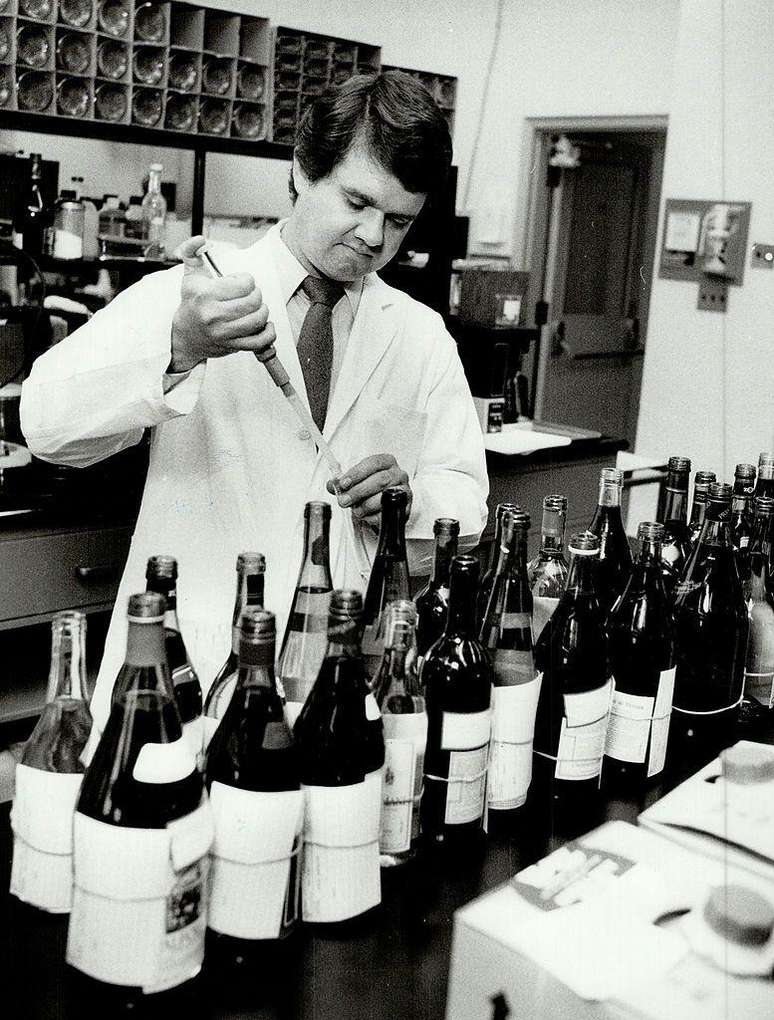

An investigation was opened and, after laboratory analyses, it was discovered that some traders were adding a substance to the wines that had become known to Brazilians in recent weeks: methanol.

“At the time, Italian oenology was still growing and quality practices and research were still in their infancy,” explains Milena Lambri, a researcher at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore specializing in oenology and food safety.

“Many producers didn’t know how to process wine correctly and decided to add methanol to increase the alcohol content and make their products more competitive.”

The ‘wine scandal’

The first cases quickly led to the discovery of large-scale adulteration, involving hundreds of thousands of liters of contaminated wine.

The Italian Ministry of Health ordered the immediate seizure of the suspected bottles and, within a few days, according to records at the time, 25 million liters of adulterated wine were confiscated.

In some bottles, authorities reported finding more than 20 times the legal limit of methanol.

Ultimately, the investigations identified two Piedmontese companies as the main centers for blending methanol into wine. But an entire network of intermediary traders was also traced who bought wine in bulk, adulterated it and resold it under low-cost generic labels.

But the scandal did not stop at the Italian borders. Soon even countries that imported Italian wines, such as Switzerland, Germany, France and Belgium, seized suspicious lots.

Italian wine exports were temporarily suspended and governments issued warnings against the consumption of Italian wine. In total, millions of liters of the drink were seized and disposed of as industrial waste across Europe.

The investigations targeted more than 60 wine companies and, ultimately, more than 40 people were formally charged, many of whom were convicted.

The main trial relating to the scandal ended only in 1993. The sentences ranged from 14 to 2 years in prison – although none of the defendants served the sentences initially imposed, given the appeals opened by the defence.

Many lawsuits seeking compensation have also been filed by victims and their families against the producers and wineries involved. Some of them took more than two decades to resolve, but ultimately no compensation was paid after the defendants were deemed unable to bear the financial burden.

And just as is happening in Brazil, which is currently experiencing a wave of methanol poisonings caused by the consumption of adulterated alcoholic beverages, the case has profoundly shaken consumer confidence.

Even producers of fine wines, who were not involved in the scandal, ended up suffering. At the end of 1986 the Italian wine market had accumulated losses of 1,000 billion lire, with a drop in the overall value of the sector of 20%. Exports fell by more than 40% and domestic sales plummeted by 70%.

The ‘turning key’

But what happened next perhaps affected the Italian wine market even more.

According to experts, it was after the methanol adulteration scandal that local wineries “switched” from quantity to quality.

“We all consider that this scandal was perhaps the most important opportunity for the Italian wine market,” says Milena Lambri.

“Producers have completely changed the way they do viticulture and oenology, starting from the field and the soil, monitoring the climate, monitoring plant growth, managing viticulture, working with fertilization, canopy management, all of this.”

According to the expert, we have begun to invest in much more knowledge and research. And consumers themselves began to worry more and more about the quality of the wine consumed.

“Italy has learned a hard lesson from this tragedy. But it has recovered, giving rise to a wine renaissance and raising its quality. Today, quality controls remain strict, but Italian wineries increasingly aim for excellence,” says Gaetano Cataldo, sommelier and consultant for the Italian wine market.

The scandal also forced institutional modernization: stricter rules, laboratory controls, safety certifications.

A 1992 law became a milestone in the regulation of designations of origin in Italy, establishing a clear and rigorous structure for the production and marketing of designation of origin wines.

As a result, wines began to be classified by grape type, place of origin, cultivation methods and alcohol content, making it easier for consumers to identify quality.

The implementation of the law was also accompanied by a strict control and inspection system, with the creation of national and regional committees responsible for supervision.

“The system has also helped traceability and thanks to it it is now possible to control the entire production chain of a wine”, summarizes Gaetano Cataldo.

The changes they made also served as a sort of “quality screening,” Lambri says.

“Only the most attentive and interested in promoting a new line in wine culture and enology survived,” says the researcher from the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart.

Lambri explains that the country today must follow European regulations on wine production, but its laws are stricter than those of the European Union (EU). “The Italian wine market probably has the strictest regulations in the world today,” he says.

Today the country exports less than in the 1980s, but its production is more focused on fine wines than in the past.

However, according to the Agricultural Payments Agency (AGEA), Italy is competing with France for the title of the world’s largest producer, with 44 million hectoliters in 2024.

And, in the end, Italians once again blindly believed in the quality of wine, so much so that the population is now the third largest wine drinker in the world, with a per capita consumption of around 42 liters per year.

For comparison, in Brazil the per capita consumption of wine in 2024 was 2.1 liters.

A lesson for Brazil?

Brazil is currently experiencing a spike in methanol poisoning cases, with 41 confirmed cases, according to the latest update from the Ministry of Health, dated Wednesday (10/15). Deaths have reached 8, with 6 cases in Sao Paulo and 2 in Pernambuco.

In the Brazilian case, initial investigations conducted by the Federal Revenue Service in collaboration with the Federal Police, the National Petroleum Agency (ANP) and the Ministry of Agriculture, indicate that methanol was used clandestinely in the production of alcoholic beverages.

The drinks affected are spirits, such as cachaça, brandy and whisky. According to the Federal Revenue Agency, there is evidence that methanol, used in chemical industries, has been diverted to fuel use and has also ended up being used illegally for adulteration in the alcohol sector.

And while they are different cases, wine industry experts say there is a lot Brazil can learn from how Italy overcame the methanol scandal.

For Gaetano Cataldo, the challenges experienced by both countries show the importance of “remaining vigilant”, as well as ensuring that the population is informed about everything that is happening, to minimize the consequences.

The expert also states that Brazil can benefit from a more rigorous traceability system, like the Italian one.

“It is also necessary and recommended to teach people to drink consciously and, at the same time, responsibly, because just a few criminals cannot affect the reputation of a country as big as Brazil,” he says.

Milena Lambri states that the way forward may be to strengthen compliance with the rules.

The expert also states that consumers are paying more and more attention to the quality of products and their origin, which obviously increases the responsibility of producers.

“Manufacturers must pay close attention to the interaction with consumer knowledge, which every year becomes richer in skills and information, especially with the Internet.”

Source: Terra

Ben Stock is a lifestyle journalist and author at Gossipify. He writes about topics such as health, wellness, travel, food and home decor. He provides practical advice and inspiration to improve well-being, keeps readers up to date with latest lifestyle news and trends, known for his engaging writing style, in-depth analysis and unique perspectives.