Since it is not known exactly what causes this disease on the rise worldwide, finding an effective cure is not easy.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, life-altering condition of those who suffer from it and the incidence of which is increasing dramatically worldwide.

It is extremely difficult to cure the disease, and many people think that available treatments simply do not work for them.

Over the last 30 years there has been an increase of almost 50% in the number of cases, which today affect around 5 million people.

The disease should not be confused with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which is a condition that affects the digestive system. IBD has other consequences.

The term is used to describe two serious diseases called Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

More women are diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, while more men are diagnosed with ulcerative colitis.

People with IBD may experience a variety of symptoms, from diarrhea and blood in the stool to weight loss and stomach pain. This may seem no worse than mild food poisoning. However, this is no ordinary stomach ache.

The experiences are often extreme. People with IBD may suffer excruciating pain and, in some cases, require surgery to remove parts of the intestine.

This is done by redirecting the intestines to a hole in the abdomen, where the stool is collected in a colostomy bag.

However, we still don’t fully understand the cause of IBD.

The impact of inflammation

The main symptom of IBD is excessive, uncontrolled inflammation, a sign that typically appears when the body is fighting an infection.

While inflammation is an important aspect of our immune system, in IBD it occurs when the body is not under attack. Because we don’t know what causes this overreaction, treatments are limited to controlling the uncontrolled immune system.

Inflammation is controlled by cell signaling. Our cells detect bacteria using receptors that bind to parts of those bacteria. This activates the receptor, causing it to send a signal to the proteins, and each protein sends more signals, creating a cascade of signals. This is what tells the body that it is under attack.

Many treatments follow the strategy of intercepting the signals and preventing the signaling cascade from starting. However, for many people these treatments are not effective.

Scientists are trying to target a different protein network, called NOD2, that is often out of control in people with IBD but is not targeted by current treatments.

One protein, called RIPK2, seems like a promising target, as it is found only in this network.

Researchers at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory are studying its structure to help scientists design a new medicine that can block the signals of this protein.

The importance of the microbiome

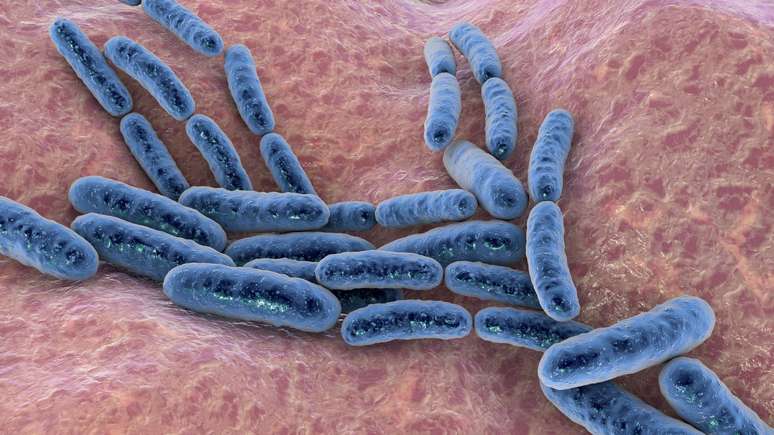

Another inspiration for new treatments comes from the bacteria in our gut. This community of bacteria, called the gut microbiome, has been linked to all kinds of health problems, from asthma to obesity.

Gut bacteria work closely with our body and play a vital role in digesting food and controlling our immune system.

In a healthy person there is a delicate balance between intestinal bacteria and the immune system. Disruption of this balance can lead to illnesses, ranging from mild discomfort to more serious long-term conditions.

Researchers are trying to understand how our bodies interact with gut bacteria and what changes when people develop IBD.

The gut microbiome is an ecosystem. Just as there are animals in a forest that eat different things, microbes can form a food web. Some bacteria consume one type of food, while others feed on others.

Some depend on waste released by other bacteria after eating. Alteration of the gut microbiome is now believed to be a hallmark of IBD and contributes to its development and progression.

It’s a chicken and egg situation. Is there any change in the bacterial and food network that alters our body? Or does something else in the body, such as our immune system, alter the food chain, thereby limiting the growth of bacteria?

Scientists are not sure of the answers to these questions.

Rather than trying to figure out what happens first, a team at the Hudson Institute for Medical Research in Australia is focusing on studying which interactions in the food chain are most affected by IBD.

This could help scientists prioritize certain gut bacteria, or their food source, to restore balance to the microbiome and improve patients’ symptoms.

The hope is that this specialized targeting of the microbiome will lead to more effective and long-lasting treatments.

While we still have a long way to go before these therapeutic hypotheses become reality, this is a step in the right direction.

Finding a new signaling pathway could help control inflammation in more patients. And studying the microbiome could reveal how we can reverse the changes associated with IBD.

As key features of IBD, these advances could allow doctors to stop the disease in its early stages and reduce complications.

* Falk Hildebran is a bioinformatics researcher, Quadram Institute, UK. Katarzyna Sidorczuk is a Metagenomics researcher, Quadram Institute. Wing Koon, is a PhD student in Bioinformatics, Quadram Institute.

*This article was published on The Conversation and reproduced here under a Creative Commons license. Click here if you want to read the original version (in English).

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.