Neuroferritinopathy is a brain disease caused by a genetic mutation that leads to the buildup of iron in the brain and leaves people trapped in their own bodies.

Neuroferritinopathy, also known in Portuguese as neurodegenerative iron storage syndrome, is a rare brain disease that traps people in their bodies and appears to specifically affect descendants of the same family lineage.

As a British university begins a clinical drug trial in hopes of reversing the effects of the disease, the BBC spoke to a family of four sisters who have been diagnosed with the disease.

Liz Taylor was 38 when she discovered she would lose the ability to walk, talk and even eat.

He felt pain in his hands which, after a series of tests requested by doctors in Newcatle, United Kingdom, led to the diagnosis of a neurological disease for which there is no cure.

“I remember after the diagnosis she ran outside crying,” recalls Liz’s daughter, Penny, now 38.

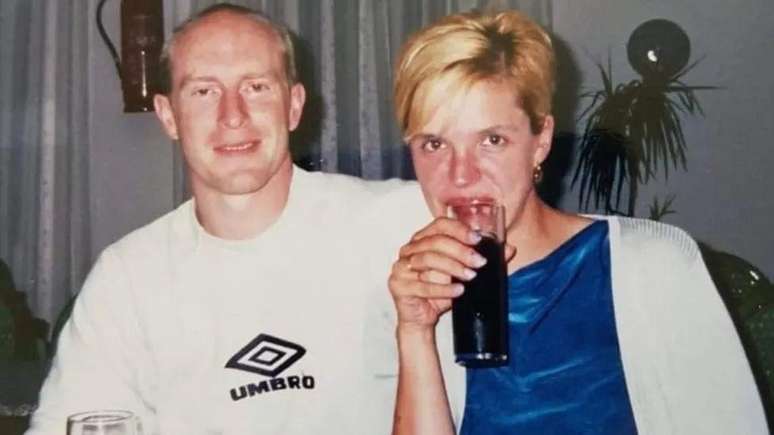

James, Liz’s husband, had to watch helplessly as his wife’s health deteriorated.

At 59, Liz is trapped in her own body.

His mind is still fully active, but James can only communicate with his wife through facial expressions and eye movements.

After Liz’s diagnosis, the Taylor family received more devastating news in the years that followed.

Liz’s three sisters were also diagnosed with neuroferritinopathy.

The family, who live in Rochdale, near Manchester, UK, had never heard of the condition.

According to the most recent estimates, scientists believe that there are only 100 patients worldwide suffering from this disease.

Most of those affected descend from the same family line originating from the Cumbria region of the UK.

The condition is often misdiagnosed as Parkinson’s disease or Huntington’s disease.

In the early 2000s, however, scientists discovered that it was actually a new disease and called it neuroferritinopathy, since it is caused by a buildup of iron in the brain.

Experts have discovered that a genetic mutation carried by these individuals causes iron – a mineral essential for health – to enter the brain, but cannot leave there and begins to accumulate over time.

Life inside the shell

But there is good news on the horizon: a clinical study will be carried out at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom to test whether a drug already used to treat other diseases can also work against neuroferritinopathy.

The expectation of scientists involved in the project is that the drug could remove accumulated iron to stop, reverse or perhaps even cure some patients.

The study offers a glimmer of hope for Liz and her sisters, including 61-year-old Heather Gartside.

Stephen, Heather’s husband, says that she also understands everything that happens in the world around her, but can’t communicate.

Heather can barely move and can’t speak.

“We had seen Liz get worse and knew it would change our lives,” recalls Stephen, who now dedicates himself to caring for his wife.

He tries to ask if Heather can help him find the words to describe how difficult it is to deal with the situation, but she can’t answer.

Looking at Liz, James adds: “She lives inside this shell, it must be frustrating.”

Neuroferritinopathy was only discovered after doctors noticed an increasing number of individuals in the Cumbria region exhibiting similar symptoms.

Professor John Burn, of Newcastle University, after whom the disease is named, found that almost all known cases probably descended from the same ancestor.

Analyzing the matter, he managed to go back in time and find that all the patients have the same family lineage, the common surname of which is Fletcher.

They have a common ancestor who lived in the town of Cockermouth in the Cumbria region.

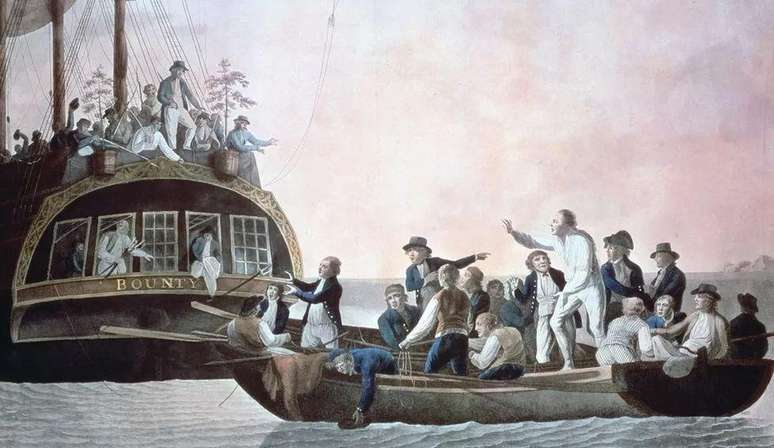

Investigations were also carried out to see whether these individuals with neuroferritinopathy might have a common ancestry with Fletcher Christian, known in the UK for leading a mutiny in April 1789.

This individual was originally from the same region of Cumbria, but for now this suspicion remains without concrete evidence.

On the road to recovery?

Now, almost 25 years after the disease was recognized by Science, neurologist Patrick Chinnery, of the University of Cambridge, is about to start a clinical trial with deferiprone.

The doctor hopes that this medicine, already used to treat other diseases, will be able to “remove the iron from the brain” and stop the disease.

“Imaging tests show where iron is concentrated in the brain. In people who have inherited this genetic mutation, this accumulation is evident,” says Chinnery.

“But it can take up to 40 years for patients to start having symptoms.”

After patients have experienced symptoms for about ten years, the excess iron begins to cause damage to the brain itself and the tissue that supports the nervous system.

“Our main goal [com o teste clínico] is to stop the disease and that can lead to some reversal of the discomfort,” says Chinnery.

“Drug repositioning studies are an effective way to use already approved treatments and apply them to new conditions and diseases,” explains Dr. Catriona Crombie, of LifeArc, an organization that works in the field of rare diseases and donated the necessary sum for research at the University of Cambridge.

If the scientific trial is successful, Chinnery believes that all doctors will be able to administer the treatment to patients even before symptoms appear: a genetic test can find the mutation and allow action before the degeneration begins.

According to experts, it is a “potential cure” for neuroferritinopathy.

The expert also says that the study could pave the way for treating other conditions linked to iron accumulation in the brain.

“If we can demonstrate that reducing iron prevents damage to nerve cells, it is logical that this approach could also be useful against Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s,” he adds.

‘I try not to think about it’

Trials with deferiprone bring hope where there was no prospect of an effective treatment.

Liz’s daughter Penny helps care for many family members, but she doesn’t yet know if she has the disease.

“I try not to think about it,” he says

“If you focus too much on the topic, I think everything can happen even faster,” he adds.

Penny says she doesn’t have many expectations from clinical trials with deferiprone, but stresses that good results would mean “everything” to her and her family.

Stephen, Heather’s husband, agrees. “If this medicine slows down the progression of the disease, that’s already a victory.”

“Now, if the treatment could actually cure, then that would be amazing and absolutely wonderful.”

“And that means a lot, doesn’t it?” concludes Stephen, looking at his wife.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.