The killings carried out by the country’s ethnic majority occurred between April and July 1994.

In 1994, in just 100 days, approximately 800,000 people were murdered in Rwanda by ethnic Hutu extremists. The massacre was an attempt to exterminate the Tutsi minority and it is estimated that around 70% of them died.

What was Rwanda like before the genocide?

About 85% of Rwandans are Hutu, but the Tutsi minority has long dominated the country.

The division of citizens by ethnicity is a legacy of the colonial period.

When the Belgians colonized Rwanda at the end of the 19th century, they classified the population according to their group, creating identity cards that indicated who were Hutu and who were Tutsi.

From this document a division was also created in which the Tutsis were identified as a dominant and superior ethnic group that had the best jobs, relegating the Hutu majority to being a subordinate and submissive group.

The divisions of the colonial government were exacerbating tensions and resentment within Rwandan society.

Ethnic differences came to a head during the country’s independence, when in 1961 the Hutu majority took control of the government, abolishing the Tutsi monarchy and declaring the Republic of Rwanda.

Dozens of Tutsis have fled to neighboring countries, including Uganda. There, Tutsi exiles formed a rebel group, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).

His main goals were to overthrow the Rwandan government and end the exile of the Tutsi.

In 1990, RPF fighters invaded the country, sparking a civil war with the Hutu; they continued to fight until a peace agreement was reached in 1993.

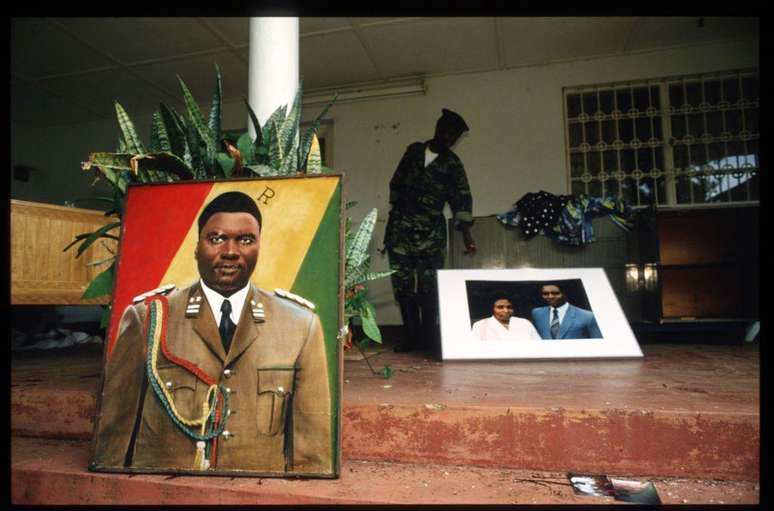

With the agreement the civil war ended and a transitional government composed of Hutu and Tutsi was created, led by Juvenal Habyarimana, of Hutu ethnicity.

But on April 6, 1994, a plane carrying President Habyarimana and his Burundian counterpart, Cyprien Ntaryamira, also a Hutu, was shot down by two ground-launched missiles, killing everyone on board.

The authorship of the attack remains disputed. Hutu extremists blamed the RPF. And the RPF claimed that the attack was carried out by Hutu extremists opposed to negotiations with the RPF – and that the plane had been shot down as an excuse to carry out genocide.

Immediately the Hutu extremists began the massacre against the Tutsis.

How was the genocide carried out?

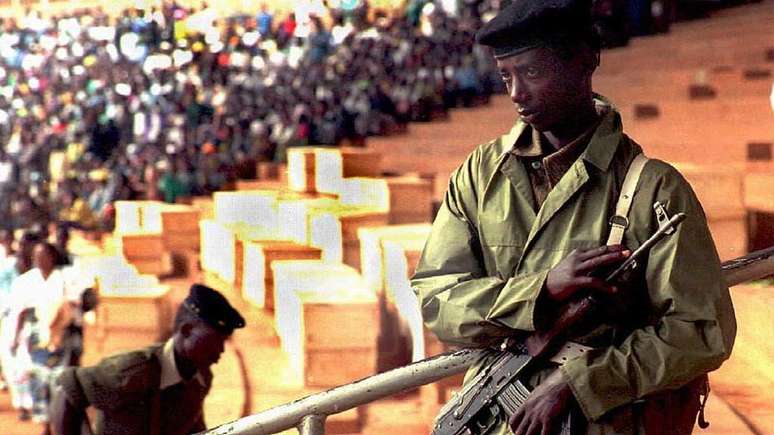

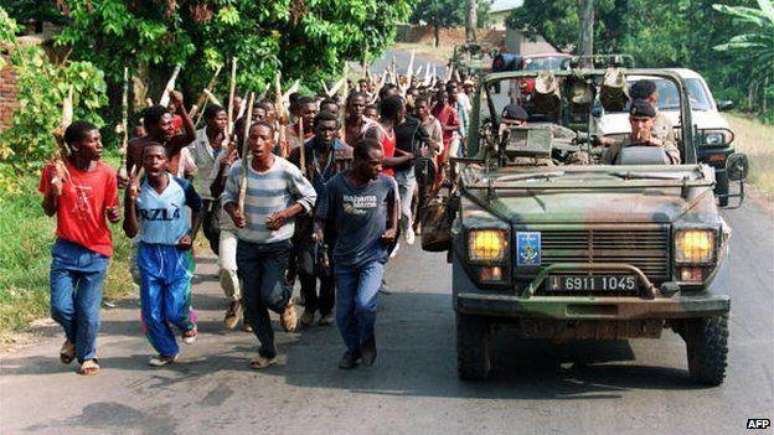

Everything was meticulously organised. Lists of government opponents were drawn up and handed over to Hutu militias, who took to the streets to kill Tutsi targets and their families.

Moderate Hutus who opposed the government were also murdered.

Over the next three months, neighbors killed other neighbors, and even husbands killed their Tutsi wives, saying that if they refused, they would be killed.

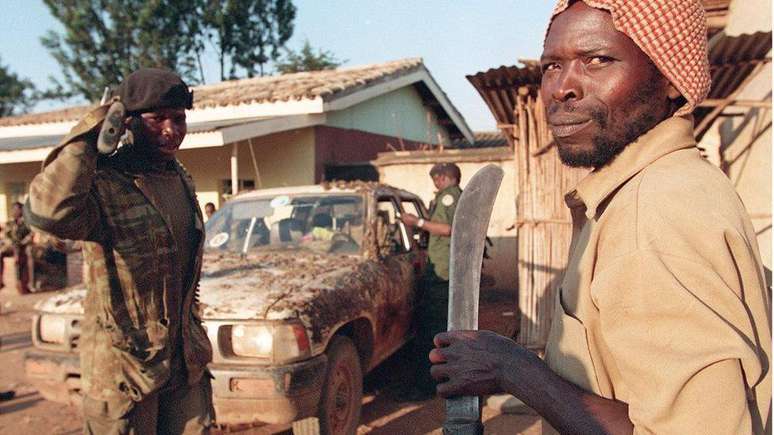

At the time, identity cards in Rwanda included residents’ ethnic group, so militias set up checkpoints where Tutsis were stopped and killed, often with the machetes that most Rwandans usually had at home.

Thousands of Tutsi women were kidnapped and sexually enslaved.

Why was he so cruel and violent?

Rwanda has always been a tightly controlled society, organized like a pyramid from each district to the top of the government.

The then ruling party, the MRND, had a youth wing called Interahamwe, which transformed itself into several militias to carry out the massacre of the Tutsis.

The weapons and target lists were handed over to local groups, who knew exactly where to find the victims.

Hutu extremists created a radio station, RTML (Rádio e Televisão Livre de Mil Colinas), and newspapers that spread propaganda and hate speech against the Tutsis, urging the population to “eliminate the cockroaches”, which meant killing the Tutsis.

The names of important people who were to be murdered were read out on the radio.

Priests and nuns were also later convicted of killing people, including some who sought refuge in churches.

By the end of the 100-day massacre, approximately 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus had been murdered.

Did the international community try to prevent the genocide?

The United Nations (UN) and Belgium had forces in Rwanda, but the UN mission was not ordered to stop the killings.

A year earlier, several American soldiers had been killed in a battle in Somalia and dragged through the streets of the capital Mogadishu by enraged Somalis.

The event, broadcast on American television and which sparked national outrage, pushed Washington to decide not to get involved in another African conflict, which is why the Americans did not intervene in Rwanda.

Belgians and UN peacekeepers withdrew from Rwanda after ten Belgian soldiers were killed in the massacre.

The French, allies of the Hutu government, sent a special force to evacuate their citizens and then set up a supposedly safe zone, but were accused of not doing enough to stop the killings there.

Paul Kagame, the current president of Rwanda, has accused France of supporting the perpetrators of the massacres, a charge that Paris denies.

How did it end?

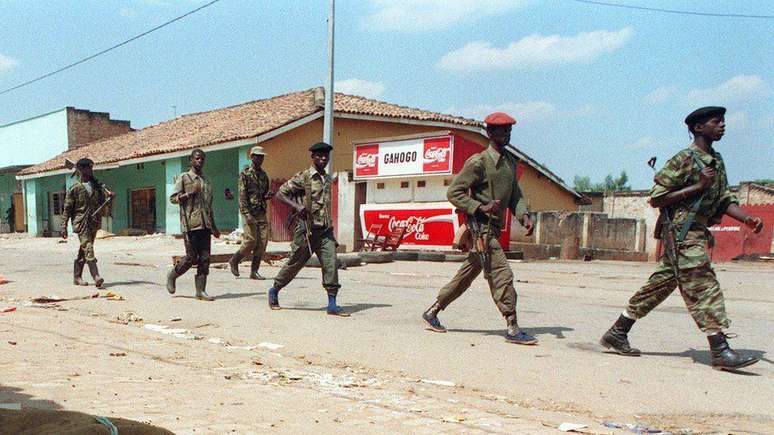

The RPF, well organized and supported by the Ugandan army, gradually conquered more and more territory, until 4 July 1994, when its forces marched towards the capital Kigali.

About two million Hutus, both civilians and some involved in the genocide, fled across the border into the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire), fearing retaliation. Others went to Tanzania and Burundi.

Human rights groups say RPF fighters killed thousands of Hutu civilians when they took power – and continued to kill Hutus when they entered the Democratic Republic of Congo to pursue members of the Interahamwe militias. The RPF denies this.

What was the impact on neighboring countries?

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, where almost a million Rwandans had taken refuge, one of the worst cholera epidemics the country had ever seen broke out.

The UN estimates that around 12,000 people have died from the disease and aid groups have been accused of letting much of their aid facility fall into the hands of Hutu militias.

The RPF, which was already in power in Rwanda, welcomed armed groups fighting both Hutu militias and the Congolese army, which was aligned with the Hutus.

Rwanda-backed rebel groups eventually marched on the Democratic Republic of Congo’s capital, Kinshasa, and overthrew the government of Mobutu Sese Seko, installing Laurent Kabila as president.

But the new president’s reluctance to confront the Hutu militias sparked a new war involving six countries and led to the creation of a series of armed groups that fought for control of this mineral-rich country.

An estimated 5 million people died as a result of the conflict that lasted until 2003 – and there are some armed groups still active today in areas near the border with Rwanda.

Has anyone been prosecuted?

The International Criminal Court was created in 2002, long after the Rwandan genocide, so it has been unable to prosecute those responsible.

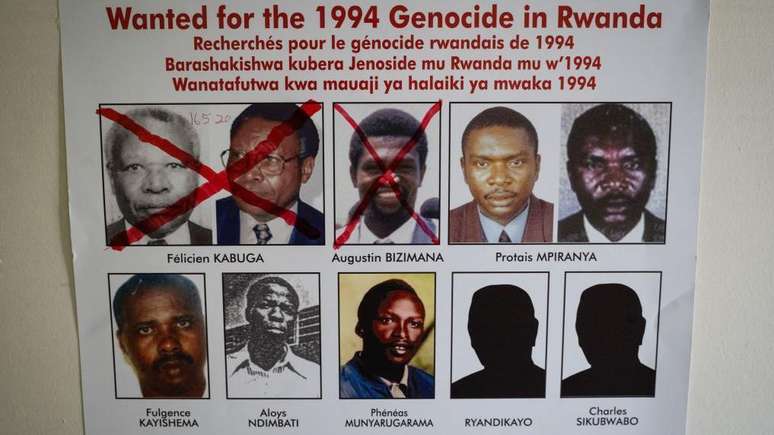

But the UN Security Council created the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, in the city of Arusha, Tanzania, to try those responsible for the massacre.

A total of 93 people were indicted and, after long and onerous trials, dozens of senior officials from the former regime were convicted of genocide, all Hutu.

In Rwanda, community courts, known as gacacato speed up the trial of hundreds of thousands of genocide suspects awaiting trial.

Around 10,000 people died in prison before being brought to justice.

For a decade, until 2012, 12 thousand courts gacaca they gathered once a week in villages across the country, often outdoors, in a market or under a tree, adjudicating over 1.2 million cases.

His goal was to achieve truth, justice and reconciliation among Rwandans, as “gacaca” means to sit down and discuss a topic.

How is Rwanda doing now?

President Kagame has been praised for transforming the small, devastated country through policies that encouraged rapid economic growth.

He also sought to turn Rwanda into a technology hub.

But his critics say the president does not tolerate dissent – and several opponents have died inexplicably, both at home and abroad.

Of course, the genocide remains a very sensitive issue in Rwanda – and it is illegal to talk about ethnicity.

The government claims this is to prevent hate speech and further bloodshed, but some say the move prevents true reconciliation.

Some of Kagame’s critics have been accused of inciting ethnic hatred, which they say is a way to marginalize them.

Kagame won his third term in the last elections in 2017, with 98.63% of the vote.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.