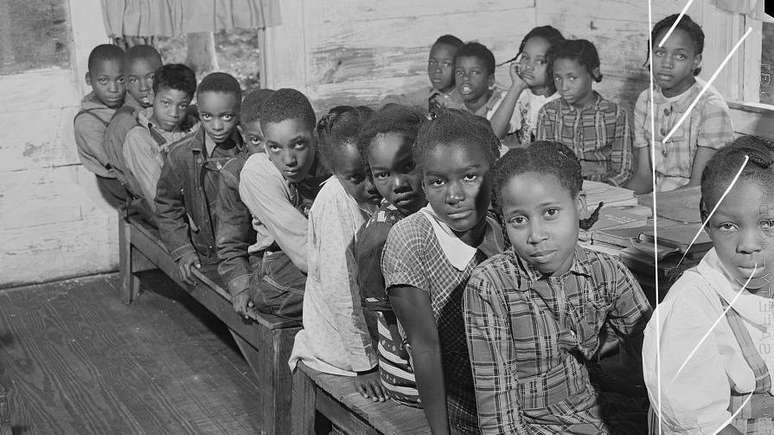

Research by psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark revealed negative impacts on black children and was crucial in the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

Among the arguments that influenced the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional and turned 70 in May, is a psychological experiment that draws attention.

In the early 1940s, more than a decade before the courts’ decision, American psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark devised a test to analyze black children’s attitudes toward race and how they developed their sense of identity and self-esteem.

The experiment involved plastic dolls that were identical except for color and showed that most black children rejected the black dolls.

Reproduced over the years in various parts of the country, the study became known as “the doll test,” and its results drew attention to the psychological, emotional, and intellectual damage segregation caused to black children.

When the legal team fighting to overturn America’s school segregation laws took their case before the Supreme Court justices, the doll tests and the Clarks’ research played a major role, as did their testimony.

Their studies would also serve as a basis for future research on how children construct and understand their own racial identity and how they absorb prejudice.

Who were the researchers?

Kenneth Bancroft Clark (1914-2005) and Mamie Phipps Clark (1917-1983) built illustrious careers in psychology and broke several racial barriers.

He was the first black student to receive a doctorate in psychology from the prestigious Columbia University in New York in 1940.

Three years later, Mamie Clark became the second black person to receive the same degree from the university.

Kenneth Clark was also the first black professor to hold a tenured position at the City College of New York and the first black president of the American Psychological Association, among other notable titles.

They both met while attending Howard University in Washington in the 1930s.

It was during this time that Mamie Clark began her academic research exploring the process of identity construction in black children.

Their studies sought to determine when these children began to become aware of their racial identity.

This line of research was furthered during the doctorate in New York and served as a basis for the couple to develop the experiment with the doll.

In 1946, the couple founded the Northside Center for Child Development, which provided therapy and educational and social services to children in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City.

Throughout their careers, the Clarks earned respect as authorities on integration in various sectors of American society and as influential figures in the civil rights movement.

“Both made significant contributions to the field of psychology and the social movement of their time,” says the American Psychological Association.

How was the test?

The doll experiment was initially designed and conducted in the 1940s to test black children’s racial perceptions and measure the psychological effects of segregation on their self-esteem.

The tests were repeated in subsequent years with students from segregated schools in different parts of the country, with similar results.

During the tests, four plastic dolls were shown to black children aged three to seven.

The dolls wore diapers and the only difference between them was their color: two were white with blonde hair and two were painted brown and had black hair.

The children had to identify the breed of the dolls, say which color they preferred and which one looked most like them.

“The doll test was my wife and I trying to figure out how black children saw themselves, whether they saw themselves as equal to other children,” Kenneth Clark said in an interview with PBS in 1985.

“We had about three or four questions related to knowledge (about the difference in color of the dolls) and some related to preferences,” the psychologist recalls.

Among the questions posed to participants were the following:

-Give me the doll you want to play with

-Give me the doll, it’s a beautiful doll

-Give me the doll it’s ugly

-Give me the doll that has a nice color

-Give me the doll that looks like a white baby

-Give me the doll that looks like a black child

-Give me the doll that looks like a black child

-Give me the doll that looks like you

Almost all children could identify the breed of the dolls.

Most wanted to play with the white doll and also attributed positive characteristics to it, such as being “nice” and having a “nice color”. At the same time, the majority attributed negative characteristics to the black doll. For Kenneth Clark, the most “disturbing” part was the final question.

“Many children were emotionally disturbed by having to identify with the doll they had rejected. Some left the room or refused to answer the question,” the psychologist observed in 1985.

“We interpreted this as an indication that color, in a racist society, was a very disturbing and traumatic component of an individual’s sense of self-worth and worth.”

In a scientific paper published in the 1950s presenting their findings, the Clarks concluded that “prejudice, discrimination, and segregation” damaged the self-esteem of black children, generating feelings of inferiority and self-loathing.

Decades later, in a PBS interview, the psychologist reiterated that the study findings indicated “the dehumanizing and cruel impact of racism in our supposedly democratic society.”

The Origins of Brown v. Board of Education

In the same interview, Kenneth Clark emphasized that doll testing began 14 years before the Supreme Court decision and that, at the time, he and Mamie had no idea that their results would play such a significant role.

But the couple’s research on black children and their expert testimony would ultimately become a crucial element in the Supreme Court’s decision.

For decades, many states, especially in the South, followed strict segregation laws, many of which were adopted after the Civil War (1861-1865) and the abolition of slavery.

The legality of these laws had been upheld by the Supreme Court, the highest court in the country, in 1896, in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson.

This decision established the legal doctrine “separate but equal“, which held that racial segregation was constitutional, as long as whites and blacks were provided “separate but equal” services.

However, as in other areas, it was common in education for schools for black students to not be of the same quality as institutions reserved for white students.

More than half a century would pass before the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson and that legal doctrine were rejected.

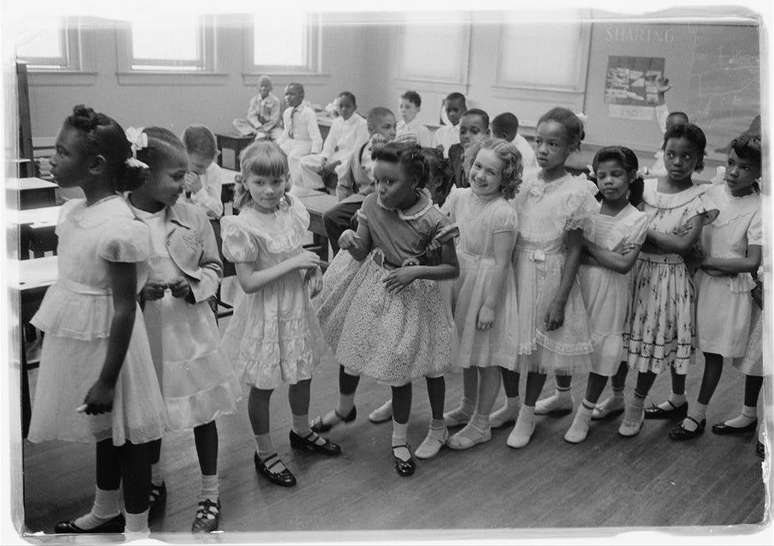

This did not happen until 1954, in the case Brown v. Board of Education, when the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

The new decision came after years of efforts by activists and academics, involving the Legal Defense Fund, or LDF, a civil rights organization that has its roots in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The Impact of the Clarks’ Research

When it reached the Supreme Court, Brown v. Board of Education consolidated five lawsuits against school districts in Kansas, South Carolina, Delaware, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

The argument for striking down the “separate but equal” doctrine was that racial segregation violated the guarantee of equal protection under the law in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

This argument was bolstered by examples of studies conducted by historians, social scientists, and other experts, some of whom were called as witnesses to highlight the negative impacts of segregation on black children and families.

The Clarks, who had previously testified in other segregation cases, were among those experts, presenting not only the results of their doll tests but also analyzing other studies on the topic.

In a 1950 article, the Clarks stated that “it is clear that the black child, by the age of five, is (already) aware of the fact that to be black in contemporary American society is a sign of inferior status.”

According to them, the sense of inferiority experienced by black children in segregated schools prevented them from receiving an equal education.

This conclusion strengthens the thesis that questions the constitutionality of “separate but equal” schools.

In announcing the unanimous decision, then-Chief Justice Earl Warren cited an article by the Clarks and their conclusions.

“Separating (black children) from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race creates a sense of inferiority about their status in the community that can influence their hearts and minds in ways that will likely never be undone,” Warren said.

Integration in schools was not immediate after the 1954 decision, and it took several years and new legal processes to achieve this goal.

“Even today, Brown’s work (against the Board of Education) is far from over. More than 200 cases involving school desegregation remain open in federal courts,” LDF states in its filing on the case.

“The legal victory in Brown did not transform the country overnight, and there is still much work to be done. But (the decision to) end segregation in the nation’s public schools provided an important catalyst for the civil rights movement, enabling progress in desegregating housing, public accommodations, and institutions of higher education.”

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.