CubeSats have already visited the Moon and Mars and are among the main components of upcoming deep space missions.

Most CubeSats weigh less than a bowling ball, and some are small enough to fit in your hand. But the impact these instruments are having on space exploration is gigantic. CubeSats, miniature, agile and economical satellites, are revolutionizing the way scientists study the Cosmos.

A full-size CubeSat is tiny and weighs about 2 kilograms. Some are larger, perhaps four times the standard size, but others weigh no more than a pound.

As a professor of electrical and computer engineering who works on new space technologies, I can say that CubeSats are an easier and much less expensive way to reach other worlds.

Rather than carrying many instruments with a wide range of purposes, these small satellites generally focus on a specific scientific goal, whether discovering exoplanets or measuring the size of an asteroid. They are accessible to the entire space community, including small private companies and university laboratories.

Small satellites, big advantages

The advantages of CubeSats over larger satellites are significant. CubeSats are cheaper to develop and test. Saving time and money means more frequent and diverse missions, as well as less risk. This alone increases the pace of space discovery and exploration.

CubeSats do not travel under their own power. Instead, they are “piggybacked” as part of the launch payload of a larger spacecraft. Placed in containers, they are expelled into space by a spring mechanism attached to their dispensers. Once in space, they light up. CubeSats typically complete their missions by burning up as they enter Earth’s atmosphere after their orbits slowly decay.

Case in point: A team of Brown University students built a CubeSat in less than 18 months for less than $10,000. The satellite, about the size of a loaf of bread and developed to study the growing problem of space debris, was launched by a SpaceX rocket in May 2022.

A CubeSat can go from design to space in less than a year.

Smaller size, single purpose

Sending a satellite into space is nothing new, of course. The Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 into Earth orbit in 1957. There are currently around 10,000 active satellites and almost all of them are involved in communications, navigation, military defense, technological development or Earth observation and study. Only a few, less than 3%, they are exploring distant space.

This is changing now. Satellites large and small are quickly becoming the backbone of space research. These space probes can now travel long distances to study planets and stars, places where human exploration or rover landings are expensive, risky, or simply impossible with current technology.

But the cost of building and launching traditional satellites is considerable. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, launched in 2009, is the size of a minivan and costs about $600 million. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter probe, with a wingspan equivalent to the length of a school bus, cost more than $700 million. The European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter, a 1,800-kilogram probe designed to study the Sun, cost $1.5 billion. And the Europa Clipper, as long as a basketball court and scheduled to launch in October 2024 to study Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons, will cost $5 billion.

These relatively large and surprisingly complex probes are vulnerable to potential failures, a not uncommon occurrence. In the blink of an eye, years of work and hundreds of millions of dollars can literally be lost in space.

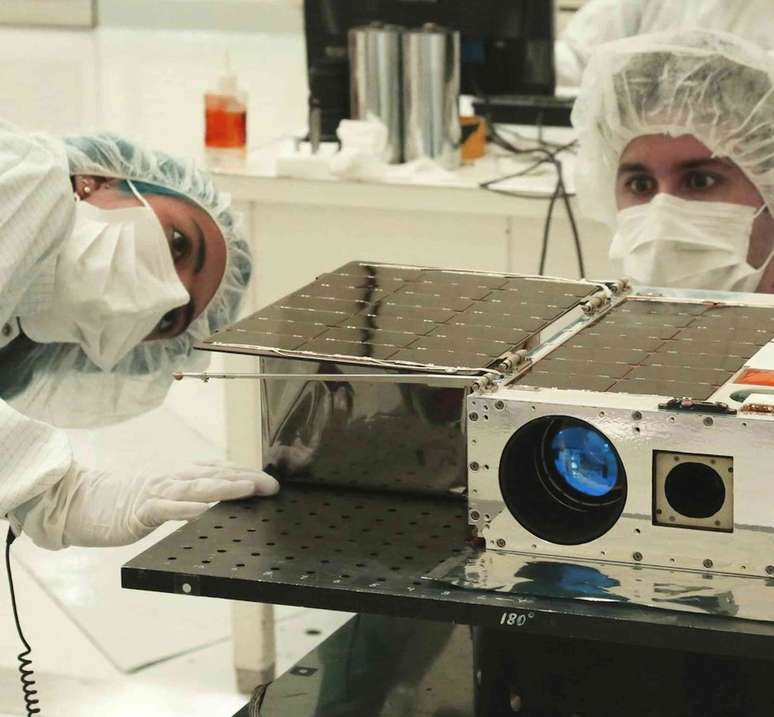

NASA scientists prepare the ASTERIA spacecraft for its launch in April 2017.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Exploring the Moon, Mars and the Milky Way

Because they are so small, CubeSats can be sent into space in large numbers in a single launch, further reducing costs. By launching them in large batches, known as constellations, multiple devices can make observations of the same phenomenon.

For example, as part of the Artemis I mission in November 2022, NASA launched 10 CubeSats. Satellites are now trying to detect and map the presence of water on the Moon. These discoveries are crucial, not only for upcoming Artemis missions, but for plans to support a permanent human presence on the lunar surface. These CubeSats cost $13 million.

The MarCO CubeSats, two of them, in turn accompanied NASA’s Insight lander probe to Mars in 2018. They served as real-time communication relays with Earth during atmospheric entry, descent and landing of Insight on the Martian surface. As a bonus, they captured photos of the planet with wide-angle cameras. They cost about 20 million dollars.

CubeSats also studied nearby stars and exoplanets, which are worlds outside the Solar System. In 2017, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory launched ASTERIA, a CubeSat that observed 55 Cancri and, also known as Janssen, an exoplanet eight times larger than Earth, orbiting a star 41 light-years away. Reconfirming the existence of this distant world, ASTERIA has become the smallest space instrument capable of detecting an exoplanet.

Two more major CubeSat space missions are on the way: HERA, scheduled to launch in October 2024, will launch the European Space Agency’s first deep-space-bound CubeSats to visit the Didymos asteroid system, which orbits the Sun between Mars and Jupiter, in the asteroid belt.

And the M-Argo satellite, scheduled to launch in 2025, will study the shape, mass and surface minerals of a soon-to-be-named asteroid. The size of a suitcase, M-Argo will be the smallest CubeSat to carry out its own independent mission in interplanetary space.

The rapid progress and huge investments already made in CubeSat missions could help make humans a multi-planetary species. But this journey will be long and depends on the ability of the next generation of scientists to develop this dream.

Mustafa Aksoy works for the State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany and the Research Foundation for SUNY. It receives funding from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU). He is a senior member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.