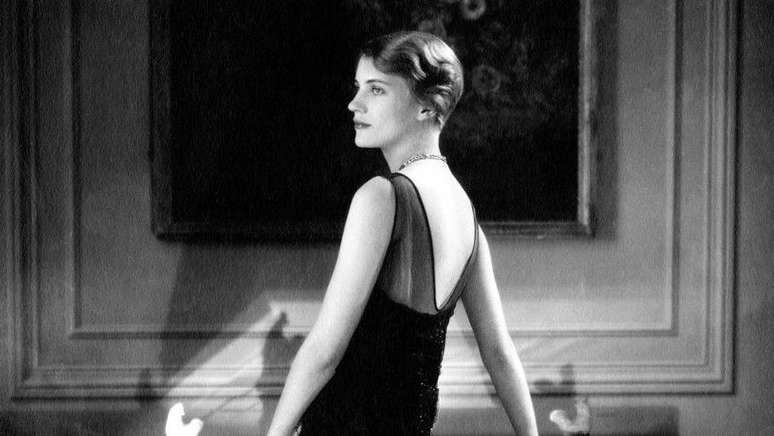

In addition to being a model, Lee Miller was an important surrealist photographer and war correspondent. He documented the atrocities of World War II.

British actress Kate Winslet fought for eight years until her biopic of American war photographer Lee Miller (1907-1977) was completed.

Lee’s film was finally released in the UK in early September. The Lee in question is Elizabeth “Lee” Miller, a remarkable American-born woman whose colorful and fascinating life often overshadows her career as a photographer.

Miller was not only a top model for fashion magazines such as Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Vanity Fair. She was also an important surrealist photographer and a courageous war correspondent, who documented the atrocities of the Second World War (1939-1945).

Lee Miller was born in 1907, in Poughkeepsie, a small industrial town about 90 miles from New York City, United States.

His father, Theodore, was an engineer, inventor and amateur photographer. He encouraged Miller’s interest in photography, purchasing his first camera, a Kodak Box Brownie, when he was 10 years old.

It was in his father’s darkroom that Miller began his first experiments with the photographic process. She also served as a model for her father, who took thousands of photographs of his daughter from birth to adulthood, including several nude portraits.

A free-spirited young man, Lee Miller eventually tired of the peaceful life in Poughkeepsie. In 1925, at the age of 18, she convinced her father to allow her to go on a study trip to Paris, France. There he found a lively city, with a strong cultural, artistic and intellectual life.

He returned in 1926 to New York, where he had a chance meeting with the founder of Vogue magazine, Condé Nast (1873-1942). He was so enchanted by Miller’s beauty and sophistication that he invited her to model for the magazine.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Miller worked with some of the leading fashion photographers of the time, such as Edward Steichen (1879-1973) and George-Hoyningen-Huene (1900-1968). But he always preferred to be behind the camera rather than be photographed.

Steichen was the one who introduced her to the American surrealist photographer Man Ray (1890-1976), who worked as an artist and commercial photographer in Paris. Miller was Ray’s muse, lover and collaborator in the French capital between 1929 and 1932.

He sometimes took over Ray’s commercial photography work so he could focus on his artistic projects. But Miller rarely received credit for his published photographs.

His work was also important in the rediscovery of a photographic process called solarization, which produces “halo-like lines around shapes and partially inverted toning areas to emphasize the contours of the body.” This process was attributed solely to Man Ray for years.

In 1932, Miller returned to New York, where he opened his own commercial studio, called Lee Miller Studios Inc. There he worked until 1934, when he moved to Egypt to marry a wealthy Egyptian businessman, Aziz Eloui Bey (1890 -1976 ). .

Egypt inspired Lee to create many surrealist images, including his own work Space portraitsince 1937. But her stay in Egypt was short-lived, as was her marriage to Aziz.

War photographer

In 1937 Miller met the British surrealist painter Roland Penrose (1900-1984) in Paris. He joined his circle of acquaintances in the south of France, which included Man Ray, the French poet Paul Eluard (1895-1952), and the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), who painted a memorable portrait of Lee Miller.

Miller moved with Penrose to London in September 1939, at the same time as the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. And, as a photographer with a surrealist background, she saw the London Blitz of 1940 as a fascinating opportunity to capture the curious and strange aspects of the Second World War.

Twenty-two of Miller’s photographs of the air raids on the British capital were included in the British Ministry of Information publication Grim Glory: Images of Britain under fire (“Sinister Glory: Images of the United Kingdom under Attack”, in free translation).

She was certified by the United States Army in 1942 and became one of the few female war correspondents traveling with the Army in Europe.

Miller was the only one to photograph the fighting and witness the liberation of Saint-Malo, France, where the Americans tested their new secret weapon, napalm. Miller’s photographs were published in the form of a photo essay in the British and American editions of Vogue magazine.

British Vogue editor Audrey Withers (1905-2001) didn’t want to focus only on fashion and beauty. He wanted to keep his readers updated on current events and social problems.

Miller and Withers worked closely to transform the fashion and lifestyle magazine into a publication that also talked about what was happening in the world, publishing articles about fashion alongside reports and images of the war.

Miller always tried to show the truth in his war photographs. In his images of the liberation of the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps in Germany in April 1945, he documented the most terrible atrocities of the Nazi regime.

The day after photographing Dachau, he posed for his most famous wartime portrait. It was taken by his friend and fellow professional, photographer David E. Scherman (1916-1997), from Life magazine.

The portrait shows Lee Miller washing himself in the bathtub of Adolf Hitler’s apartment in Munich, Germany. His appearance is tired but handsome, with boots on the floor and a photograph of the Führer resting on the edge of the bathtub.

After the war, in 1947, Miller became pregnant with her only child, Antony Penrose. He is the author of the book The Lives of Lee Miller (“The Lives of Lee Miller”, in free translation), which served as the basis for Winslet’s film. And Miller married Antony’s father, Roland Penrose.

The family moved from London to Farley Farm, in rural East Sussex, southeast England, in 1949. There, Miller turned her attention to the domestic scene, becoming a renowned cook and hostess.

But the visions she witnessed during the war haunted her for the rest of her life. Miller became addicted to alcohol. In recent days she would have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Lee Miller died at Farley Farm in 1977. She left an extraordinary photographic legacy and has since been the subject of numerous exhibitions.

*Lynn Hilditch is Professor of Fine Art and Design Practice at Hope University Liverpool, UK.

This article was originally published on the academic news website The conversation and republished under a Creative Commons license. Read the original English version here.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.