The International Atomic Energy Agency has warned of damage to some buildings, systems and equipment at the Russian-occupied Ukrainian power plant.

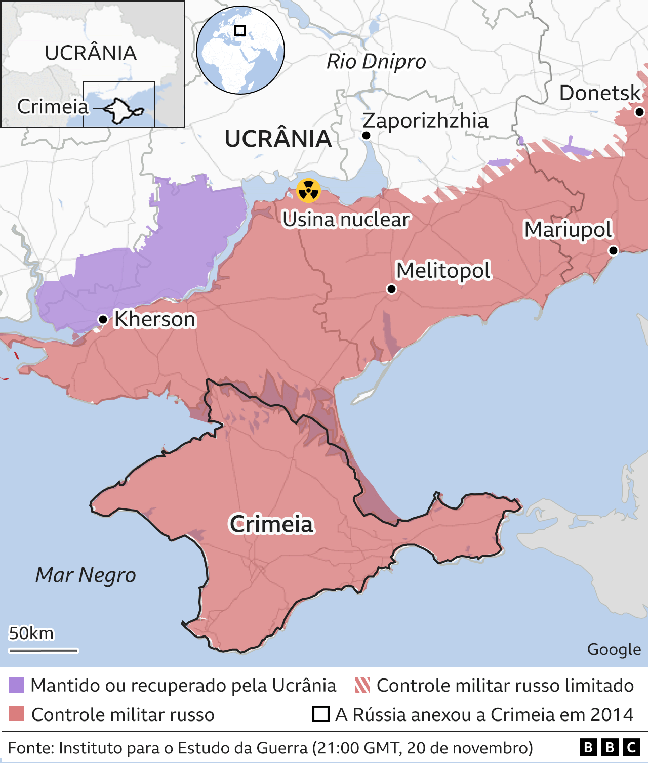

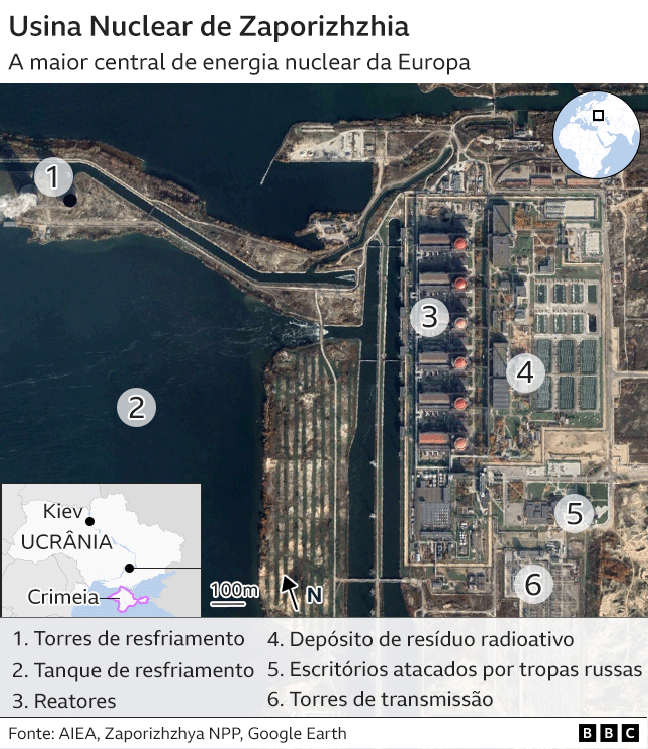

In recent days several explosions have rocked the structures of Zaporizhzhia, the largest nuclear power plant in Europe, located in southeastern Ukraine and under Russian control since the beginning of the invasion.

Russia and Ukraine have exchanged accusations of responsibility for the bombing.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has repeatedly expressed concern about attacks on the plant and has proposed establishing a nuclear safety buffer zone around it.

Bombing the nuclear power plant is like playing “Russian roulette,” Olli Heinonen, a former deputy director general of the IAEA, told the BBC.

“A single bullet in the wrong place at the wrong time will have far-reaching consequences,” warned the former UN official.

He clarified, however, that a single shell is unlikely to cause damage to the reactor itself, which is protected by meters of concrete and metal.

The risk, he said, was that the bombing would cut off the supply of electricity to the cooling system, which would mean the reactor or spent fuel would get very hot, causing the fuel to melt and release radioactivity.

Added to this is the fact that employees “can go wrong” due to the pressure they are under, if they are able to operate.

“It’s a dangerous game and it has to stop,” added Heinonen.

“The news from our team is extremely worrying,” said Rafael Grossi, head of the IAEA, whose field team has reported damage to some of the plant’s buildings, systems and equipment.

“There have been explosions at the nuclear power plant, which is totally unacceptable. Whoever is behind it must stop immediately. As I have said many times, they are playing with fire,” he added.

But, after all, what is this plant like and what are the risks?

the largest in Europe

The Zaporizhia Nuclear Power Plant, built between 1984 and 1995, is the largest nuclear power plant in Europe and the ninth largest in the world.

It has six reactors of 950 MW each, for a total production of 5,700 MW, enough energy to supply around 4 million homes.

According to the IAEA, in normal times the plant produces about 20 percent of Ukraine’s electricity and nearly half of the power generated by the country’s nuclear facilities.

The plant is located in southeast Ukraine, in Enerhodar, on the banks of the Kakhovka reservoir on the Dnieper River. It is located about 200km from the disputed Donbass region and 550km southeast of the capital Kiev.

The plant’s importance led Russia to occupy it in March, at the start of the war. Since then, both sides have accused each other of repeatedly bombing the facility.

The Russians kept Ukrainian technicians to operate the plant.

In August, the plant was temporarily disconnected from the Ukrainian power grid for the first time in its history, when a fire brought down the last remaining 750-kilovolt electric transmission line twice.

UN nuclear experts carried out their first inspection of the plant in September, accompanied by Russian soldiers, and found that the plant’s integrity had been “compromised several times”.

Differences from Chernobyl

Some analysts say that the Zaporizhzhia plant is different and safer than the one in Chernobyl, the scene of the world’s worst nuclear disaster in 1986.

Zaporizhzhia’s six reactors, unlike Chernobyl, are pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and have containment structures around them to prevent any radiation release.

“Zaporizhzhia was built in the 1980s, so it’s relatively modern,” says Mark Wenman, director of the Future of Nuclear Power Doctoral Training Center.

“It has a solid containment building. It is 1.75m thick, heavily reinforced concrete over a seismic bed. [para resistir a terremotos]…and it takes a lot to break it.”

He rejects comparisons with Chernobyl in 1986 or Fukushima in 2011. Chernobyl had serious design flaws, he explains, while in Fukushima the diesel generators were flooded, which he believes would not happen in Ukraine, given that the generators are inside the building of containment.

The Zaporizhzhia plant also does not contain any graphite in its reactor. In Chernobyl, graffiti caused a significant fire and was the source of the radiation cloud that swept across Europe.

Furthermore, PWR reactors are also equipped with fire protection systems.

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, in the United States, nuclear power plants were tested for possible attacks by large aircraft and considered safe enough, therefore damage to the reactor containment building may not be the greatest danger.

The supply risk

More worrying is the loss of power to nuclear reactors. If this happens and the backup diesel generators fail, there will be a loss of cooling. Without electricity to power the pumps around the reactor’s hot core, the fuel would begin to melt.

The plant was temporarily disconnected from the Ukrainian power grid on August 25, when a fire twice brought down the last remaining 750-kilovolt electric transmission line. The other three were mothballed during the war.

In this case, electricity was supplied via a less powerful transmission line from a nearby coal-fired power station, and diesel generators were also used, according to the authorities.

However, Ukraine’s nuclear agency says generators are not a long-term solution and that if the last power transmission line in the national grid goes down, nuclear fuel could start to melt, “resulting in the release of radioactive substances ” in the environment.

Failure of the pump and generator can cause overheating of the reactor core and destruction of plant structures.

“It wouldn’t be as bad as Chernobyl, but it could still cause a release of radioactivity, and that depends on which direction the wind is blowing,” says Claire Corkhill, professor of nuclear material degradation at the University of Sheffield in the UK. .

For her, the risk of something going wrong is real and Russia would be as exposed as Central Europe.

But Iztok Tiselj, a professor of nuclear engineering at the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia, believes the risk of a major radiation accident is minimal, as only two of the six reactors are operational.

“From the point of view of European citizens, there is no cause for concern,” he says.

The other four reactors are cold idle, so the amount of energy needed to cool the reactors is less.

the human factor

Another serious security risk could come from the fuel used in Zaporizhzhia. Once the fuel is used up, the waste is cooled in the spent fuel tanks and then transferred to a dry storage facility.

“If they were damaged, there would be a release of radioactivity, but it wouldn’t be as bad as the loss of coolant,” says Corkhill.

Iztok Tiselj believes that any release would be so small as to be meaningless.

At the heart of this crisis are the plant’s employees, who work under Russian occupation and a lot of stress. Two employees told the BBC about the daily risk of being kidnapped.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called on Russia to withdraw its troops and demilitarize the area with a “security perimeter”. Russia refused, arguing it would make the plant more vulnerable.

Officials have warned of disaster that would ensue if Russia tries to shut down the entire plant to cut off supplies from Ukraine and reconnect it to the occupied Crimea peninsula.

Mark Wenman believes that it is the human factor that poses the greatest risk of a nuclear accident, whether from chronic fatigue or stress.

“And that violates all security principles.”

If something goes wrong, they should be in top form, and they presumably aren’t, says Claire Corkhill.

In a letter signed by dozens of officials, they ask the international community to reflect:

“We can professionally control nuclear fission,” they say, “but we are powerless in the face of people’s irresponsibility and madness.”

– This text was published in https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-63727896

🇧🇷The best content in your email for free. Choose your favorite Terra newsletter. Click here!

Source: Terra

Camila Luna is a writer at Gossipify, where she covers the latest movies and television series. With a passion for all things entertainment, Camila brings her unique perspective to her writing and offers readers an inside look at the industry. Camila is a graduate from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) with a degree in English and is also a avid movie watcher.