Does an event so steeped in history, religion and splendor still take place in Britain in 2023?

The coronation of King Charles III on Saturday (6/5) is likely to showcase the kind of royal pomp that the British are famous for. But it’s also a deeply religious occasion, steeped in age-old traditions that, to some, might seem anachronistic in 2023.

Does the event retain its former significance and is a coronation ceremony necessary?

Millions of people across the UK will witness a rare event in the coming days. While the British may be used to the pageantry, crowds and street parties that accompany royal celebrations and jubilees, it has been 70 years since a coronation has been seen.

It’s a completely different event, full of curiosities: a medieval oath, sacred oil poured into a 12th-century spoon, and a 700-year-old chair housing a stone that would have roared when it recognized the rightful monarch.

Some experts liken a coronation to a wedding, but instead of a spouse, the monarch marries the state. The 2,000 people attending King Charles III’s coronation at Westminster Abbey will be asked if they recognize him as monarch. He will then be given a coronation ring and called to take the oath.

If all of this sounds like something from another era, it’s because coronation ceremonies in the UK have changed little in the last thousand years.

By law, a coronation is not required, as the monarch automatically assumes the throne upon the death of his predecessor. But coronations are a symbolic gesture that formalizes the monarch’s commitment to the role, says George Gross, who leads a research project on coronations at Kings College London.

He believes a monarch’s pledge to “uphold law and justice with mercy” in a public statement is a unique and special moment.

“In an uncertain world where leaders continually break the rules of international law, our monarch has to say ‘these are the basic things that matter’, and that doesn’t worry me.”

Merging the old and the new?

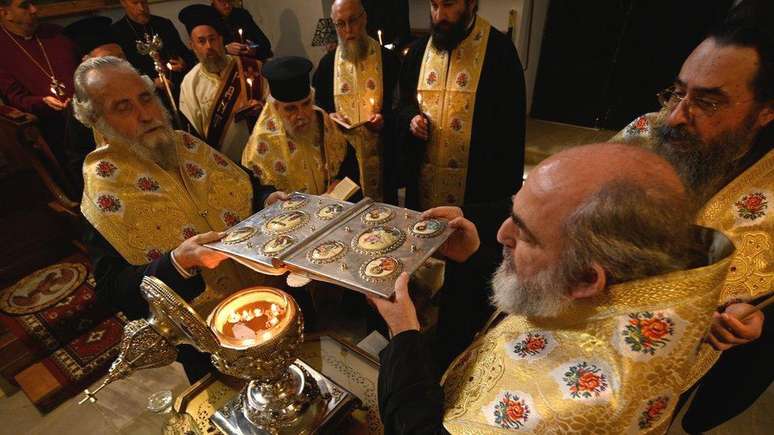

What happens next perhaps sums up the essence of the coronation: a fundamentally religious occasion. An outline of the cross is made on the head, hands and chest of the monarch with a consecrated oil, on the medieval spoon.

The anointing process elevates “the monarch almost to a priest,” explains Gross, and signals the monarch’s role as head of the church.

“It’s an Anglican ceremony and the anointing is essential as a conferral of God’s grace on the monarch,” says David Torrance, who wrote a parliamentary research paper on coronations.

“But it is also the Church of England that reminds everyone that it is one of the established churches of the United Kingdom and the monarch is its supreme governor.”

This moment is done in private because it is seen as an intimate moment and for the sake of practicality, as the monarch is wearing fewer clothes at the moment, says Elena Woodacre, director of the Royal Studies Network. The cameras are likely to move like when Queen Elizabeth was stripped of her robe and jewels during her televised coronation in 1953.

Instead of using the previous coronation oil, as some monarchs have done, a new batch was produced this year. It previously contained animal products such as civet oil and ambergris, which are found in sperm whales, but this cruelty-free, vegan version is made, in part, from olives. In a possible nod to other religions, they were nurtured at the Monastery of Mary Magdalene in Jerusalem, where Princess Alice, the king’s grandmother, is buried.

But the oil’s choice is also in line with “modern sensibilities,” Woodacre says, adding that it “blends tradition and continuity with adaptation and change” at a time when some question whether monarchy still has a place.

“The coronation is an opportunity for the king to connect to the power of the past and shape his future. All these ancient traditions, like the Abbey and the use of the spoon, help to strengthen his position.”

Does tradition matter?

Republic’s Graham Smith, who campaigns for an elected head of state, wonders whether tradition is a valid argument when coronations “have changed in scale, scope and content every time.”

“Most people don’t remember the last time, so it’s not a tradition that means anything to anyone,” she says. “It has no constitutional value, it is not binding, and if we didn’t, Charles would still be king.”

Indeed, a monarch does not need a coronation to rule and some have, such as Edward VIII, who abdicated before his coronation. European monarchies got rid of coronations a long time ago and public opinion suggests interest may be waning in the UK.

A recent YouGov poll found that 48% of respondents were very or least likely to attend the coronation. Another poll, taken around the time of the Queen’s platinum jubilee, found that while six in 10 supported the monarchy, a majority of Britons believed the royal family was less important to the country than it was in 1952.

Stephen Evans, who heads the National Secular Society, says the UK religious scene, for example, has “changed beyond recognition” since the last coronation in 1953 and “many will feel alienated by an Anglican ceremony”.

Torrance agrees that the core aspects of the ceremony may have been familiar to people then and may be less so now. But he says statistics show congregations in London are growing and many Anglican churches are full.

“When the Queen died, we had a lot of religion mixed into the ceremony. I think the Palace was surprised by the response from the public… a lot of attention was paid to it,” she says. “If there is an effort to make the coronation less exclusively Anglican, it can be taken into account that the UK now has a proliferation of different religions.”

A 21st century coronation?

An essential part of the ceremony, however, is tied to one’s faith, says Professor Anna Whitelock, director of the Center for the Study of Modern Monarchy.

“The problem is that at the center is the anointing [e] the oath that seeks to uphold the Church of England. The thing is, you can’t change the fundamental parts of the coronation, which is exclusive, it’s not different, it’s about privilege and everything that a multi-religious, multi-ethnic Britain is not.”

Whitelock agrees that attempts have been made to modernize the Coronation, such as making it smaller than before, commissioning new music and bringing in more guests, “but it’s an attempt to change the style [quando] you can’t change the substance.”

He believes any significant change would require a major overhaul, such as destabilizing the Church of England or a referendum on the monarchy, neither of which he expects to see anytime soon.

“The legitimacy of the monarchy is based on tradition and continuity, so I think if Prince William were to scrap the coronation, it would be seen as going further and weakening the institution, and I don’t think we’ve reached that point yet.”

Gross believes there are attempts to modernize the coronation in other ways, including the question of cost.

He says that while it is not uncommon for coronations to take place in difficult economic times – citing that of George VI, which took place during a great depression – the decision to reduce King Charles III’s guest list to a quarter of the numbers that attended that of his mother may be an attempt by the palace to keep costs “reasonable”.

But at a time when the public is struggling financially, critics say a coronation costing millions is a public waste of money. The Department of Culture, Media and Sport was unable to provide estimates, but it clearly won’t be free. Also, it was not possible to reveal how much the Queen’s state funeral cost last year, although, for comparison, the Queen Mother’s in 2002 cost £5.4 million (more than R$33 million in current quotes).

The public reaction to their deaths, however, suggests that there is still some level of interest in the monarchy.

An estimated 250,000 people lined up in September to see the queen, and similar numbers turned up to see her mother. Compared to the UK population of 67 million, this may seem low, but around 40% watched the funeral on TV.

Whether the coronation will have the same effect remains to be seen, though Professor Whitelock is skeptical.

“No doubt some people will look on and say that’s what Britain does best in pomp and show. But it’s a bad idea that a man who, by chance by birth, is anointed and set above like the rest of us , without being elected, and does not represent Britain religiously or ethnically”.

Source: Terra

Rose James is a Gossipify movie and series reviewer known for her in-depth analysis and unique perspective on the latest releases. With a background in film studies, she provides engaging and informative reviews, and keeps readers up to date with industry trends and emerging talents.